|

ETCHINGS OF A WHALING CRUISE,WITH NOTES OF ASOJOURN ON THE ISLAND OF ZANZIBAR.TO WHICH IS APPENDED A BRIEFHISTORY OF THE WHALE FISHERY,ITS PAST AND PRESENT CONDITION.BY J. ROSS BROWNE.ILLUSTRATTED BY NUMEROUS ENGRAVINGS ONSTEEL AND WOODNEW YORK:HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS,82 CLIFF STREET1846Illustrations J. Ross Browne, (1817-1875) Notes |

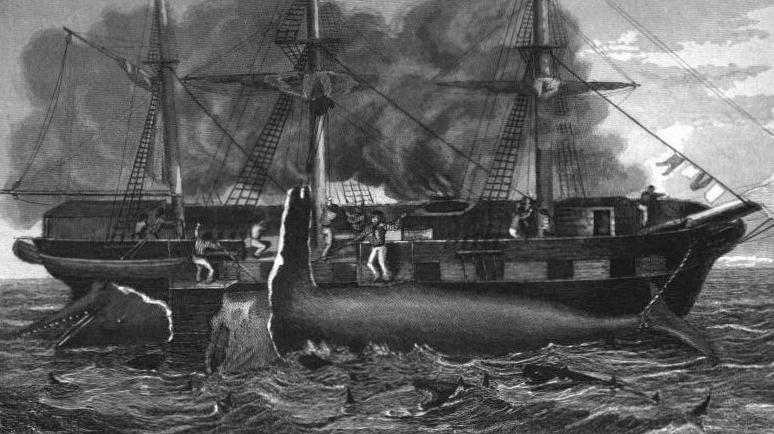

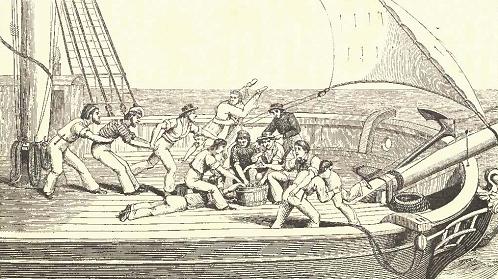

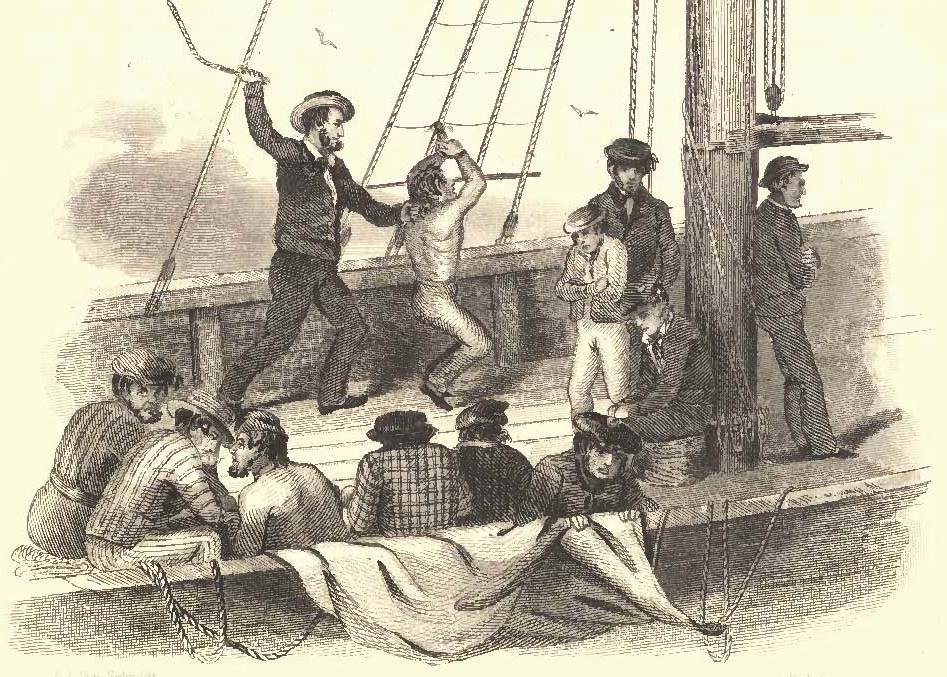

CUTTING IN & TRYING OUT. |

|

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1846

By HARPER & BROTHERS, In the Clerk's Office of the Southern District of New York |

gratify malice, can not, therefore, be justly attributed to me. My design is simply to present to the public a faithful delineation of the life of a whaleman. In doing this, I deem it necessary that I should aim rather at the truth itself than at mere polish of style. A due regard to fidelity induces me to present the incidents and facts very nearly in their original rude garb. I have no faith in softening or polishing stern realities. Let them go before the world with all the force of truthfulness; and if they can effect nothing, the blame will not rest upon the narrator. I claim no higher credit than that of being an accurate reporter of passing events, with the privilege of commending what is right, and dissenting from what is wrong. I have suffered too much, not to feel the woes of others. Where reproof is merited, where injustice has been done, where human rights have been invated, I shall ever lift up a deprecating voice. It is one of the glorious prerogatives of a freeman to denounce tyranny and injustice; and no fear of exciting enmity shall deter me from exercising it. I have espoused the cause of seamen; I have shown the flagrant abuses to which they are subject; I have exposed the cupidity of owners and the tyranny of masters; and I do not expect to escape censure. No man ever enlisted in a good cause without making enemies. Truth is always offensive to those who have cause to fear it. If, therefore, there be any who may feel disposed to abuse me for exposing the wrongs of seamen, they may rest assured I prefer their censure to their praise. Mr. Richard H. Dana has given, in his "Two Years fefore the Mast." * a faithful and graphic delineation of life in the merchant service. The thanks of every just man are due to him for his noble exertions in behalf of the suffering mariner. Previous to the publication of his work, little was known of the real hardships encountered by the sail- * Harper's Family Library, No. 106. |

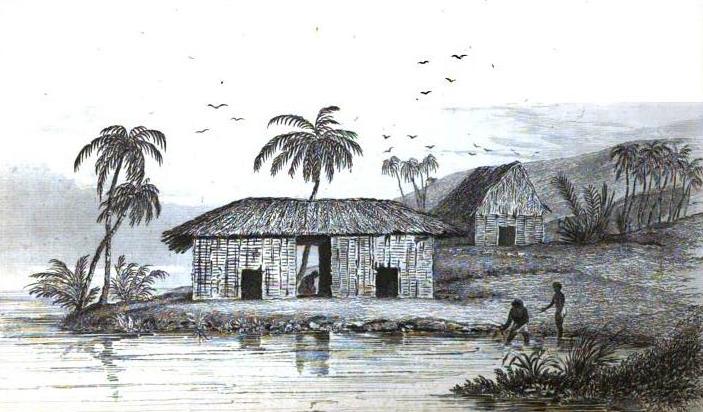

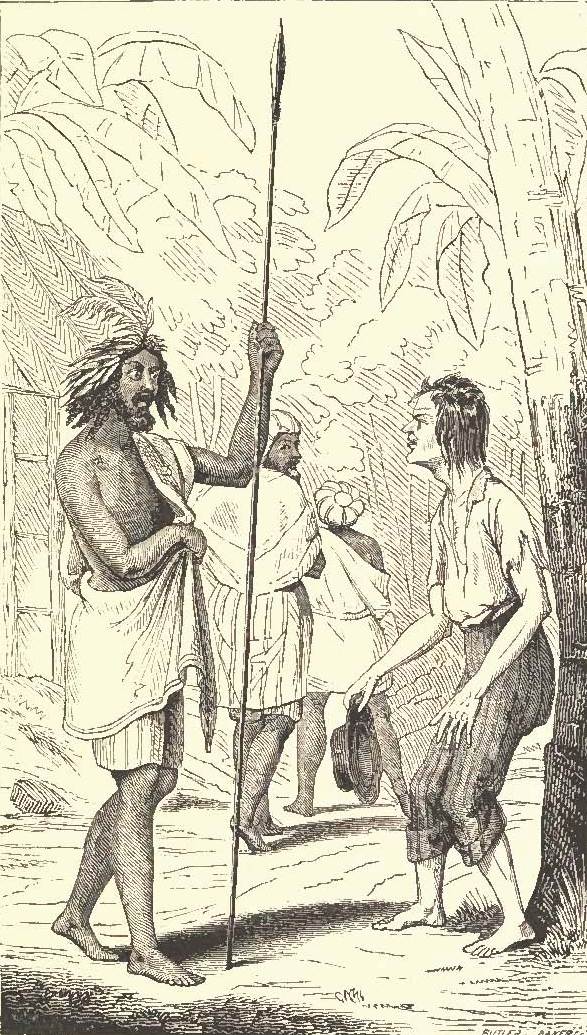

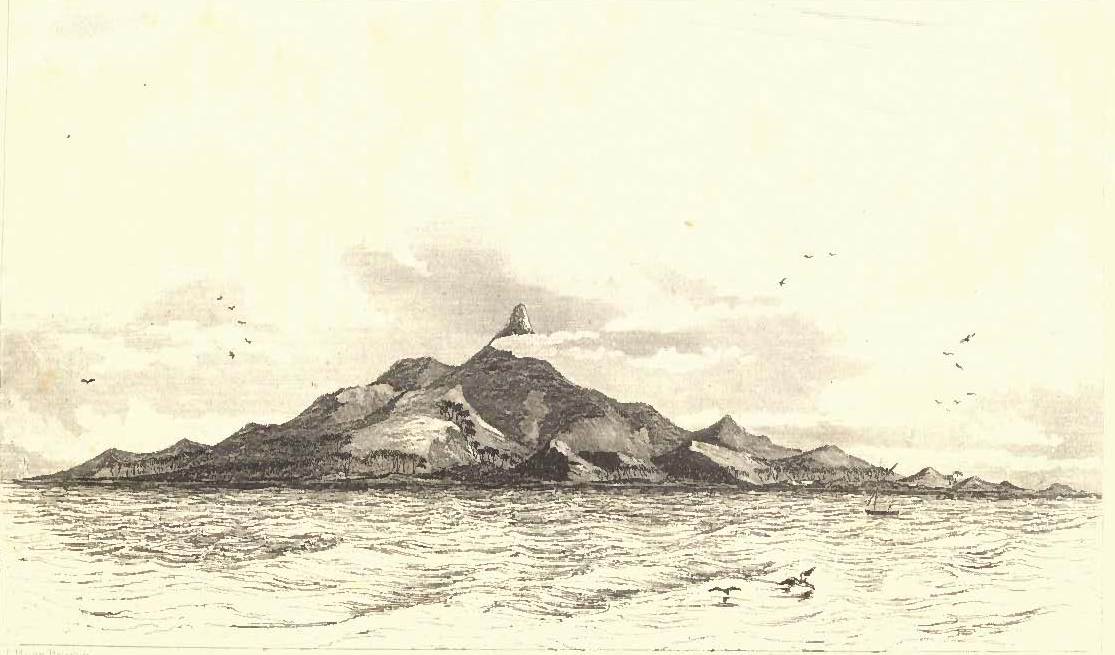

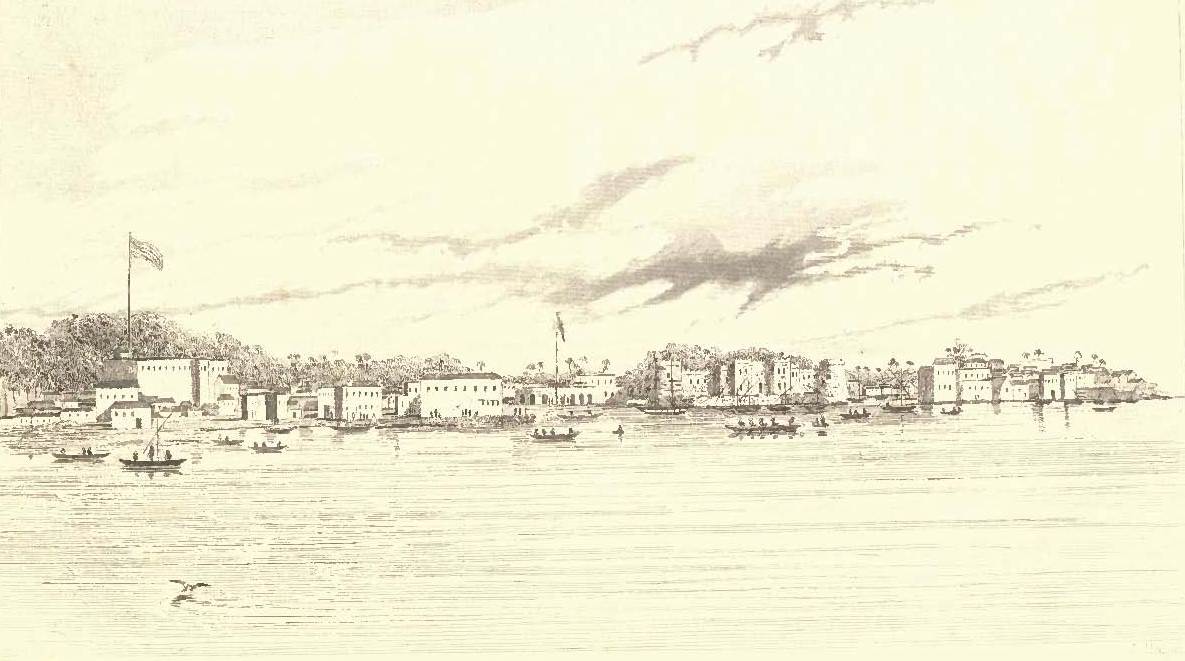

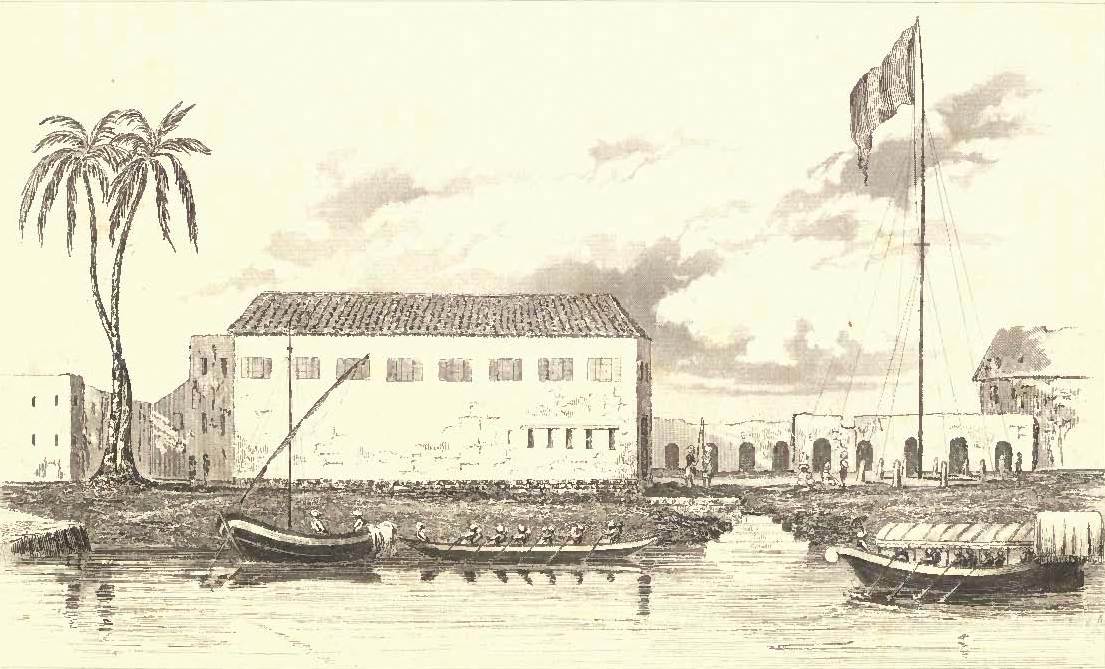

ors; and to Mr. Dana may be attributed the moral revolution which has since taken place in the merchant service. I should be very backward in presenting my narrative to the public, after the brilliant success of a work written under nearly the same circumstances, if it were not that each describes an entirely different service. The duties, treatment, mode of living, and every thing connected with the voyage of a whaleman, differ widely from those of the merchant sailor. I believe no one has yet attempted a full and continuous narrative of forecastle life in the whale fishery from actual experience as a hand before the mast. Having had no previous acquaintance with the topography of the islands visited in the course of our cruise, or the manners and customs of the inhabitants, and no books to which I could refer while at sea, I was obliged to rely chiefly upon my own observation; so that the little which I may have added to what is already known of those islands must be taken in connection with the circumstances under which I obtained my information. It should be borne in mind that this is not designed as a work of reference for geographers and naturalists. I claim no higher rank for it than that of a mere chronicle of incidents and adventures. The notes of a sojourn on the Island of Zanzibar will, I trust, derive some interest from the fact that very little is known of that island and its inhabitants. Since the embassy to the courts of Siam and Muscat in 1832-3, but more especially since the visit of a vessel belonging to the Imaum of Muscat to this country a few years since, it has become customary to laud this Arabian potentate in the most extravagant terms of admiration. I have no disposition to detract from his high reputation; but, at the same time, I must say, no living sovereign has been more universally misrepresented, both as regards character and power. I enjoyed, perhaps, a better opportunity of becoming ac- |

quainted with the true character of the Imaum of Muscat, the extent of his dominions, and the condition of his subjects, than any of those writers who have described, in such glowing terms, the splendor of his court, his munificence toward the American government, and his unlimited power over the islands near the eastern coast of Africa. I take pleasure in acknowledging my indebtedness to Mr. A. A. von Schmidt, the talented artist who has so admirably executed the drawings. An intimate personal acquaintance with this gentleman for many years past induced me to show him my rough sketches taken during the voyage; and, through his skill and kindness, I am now enabled to present them to the reader in a more perfect state, but with all the spirit and freshness of sketches from life. I am happy to perceive that his skillful pencil is not idle, having been called into requisition by the Honorable Edmund Burke, commissioner of patents. Though young in years, it has been my lot to encounter many of the vicissitudes of a wandering life. May I not be indulged, then, in the privilege of an adventurer – that of telling of dangers past in my own way? If I have dwelt at some length on the dark side of things, it will be admitted that I show a strong preference for the sunny side. It is no pleasure to me to harp upon the ordinary frailties of human nature. Indeed, I think I may be allowed to say, that "I own the good, while smarting with the ill, With these few remarks in the way of explanation, I submit my narrative to the indulgence of the public; and if it should be the means of directing attention to the unhappy happy condition of that class with whom I was for a brief period of my life associated, I shall consider myself repaid for the trials and hardships of the past.

J. R. B.

Washington, D. C., July, 1846. |

CONTENTS.CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

|

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

|

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

CHAPTER XVI.

|

CHAPTER XVII.

CHAPTER XVIII.

CHAPTER XIX.

CHAPTER XX.

CHAPTER XXI.

CHAPTER XXII.

|

CONCLUSION.

APPENDIX.

|

ETCHINGS OF A WHALING CRUISE,WITH NOTES OF ASOJOURN ON THE ISLAND OF ZANZIBAR, ETC. |

ILLUSTRATIONS.

|

ETCHINGS OF A WHALING CRUISE.CHAPTER I.

I Deem it but fair that the reader should know the circumstances under which I commenced my career of adventure. There is nothing uncommon in them – nothing that I have the slightest reason to conceal; and it is only because I believe the interest of a narrative of this kind depends, in a great measure, upon the previous pursuits and associations of the author, that I make any allusion to matters which would otherwise be of so little moment. When a man abandons all the enjoyments of civilized life, signs away his freedom, and voluntarily brings trouble upon his own head, it may naturally be presumed that he has wise motives for doing so. I am not sure that this was precisely my case. If I had any motives for so unaccountable a course, they were merged in the vague but absorbing desire inherent in me from early boyhood to see the world. |

I date the circumstances which led to my cruise as far back as 1838. In that year I performed a voyage in a trading-boat from Louisville to New Orleans. The incidents of a year's life on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers gave me a thirst for adventure; and I resolved to gratify it with as little delay as possible. My design was somewhat ambitious. I was determined to travel as a gentleman of leisure; though, to accomplish this object, it was necessary I should have means. In racking my brain to find a panacea for empty pockets, I could think of no profession in which it was likely I should have so little competition to contend against as that of stenographer, from the fact that it requires more labor to become proficient in it than most other professions. Besides, I had a penchant for scribbling. I set to work at once, and studied Gurney's, Taylor's, and Gould's "hieroglyphics" with so much zeal, that at the expiration of about a year I was a mere hieroglyphic myself. In November, 1841 – then in my nineteenth year – I left Kentucky for Washington City. The prospect before me was quite inspiring. I was about to see the great men of the nation assembled in council; to hear, for the first time in my life, the thrilling eloquence of our great orators; to be the humble medium of preserving some of their flights for future ages to admire! What a glorious galaxy of intellectual light was soon to shed its rays upon my boyish mind! |

On my arrival in Washington, I was fortunate enough to procure a good situation as reporter in the Senate. A long session had just opened. According to the nicest calculation, I thought myself (prospectively) in possession of at least six or eight hundred dollars; and I spent my leisure hours laying out the plan of my grand tour. First, I intended visiting France. If I should find nothing very attractive in Havre or Paris, I would immediately proceed to Italy, see all the curiosities, and, after touching at various ports in the Mediterranean, cut across from Constantinople to Alexandria and Cairo, visit the Pyramids, take a flying trip across the Isthmus of Suez, and return by the Cape of Good Hope. All this I intended doing in an economical, though gentlemanly way. The prospect of being able to accomplish my wishes in so short a time encouraged me to diligent application. Not a moment of my time was misspent. I was really a model of industry. When my work was over, I hurried to the Library of Congress to study the history, geography, and literature of the places to be visited in my grand tour. In this way I passed many of my leisure hours with pleasure and profit. As the session advanced, much of my youthful enthusiasm began to wear away. A nearer acquaintance with the distinguished political leaders by no means increased my respect for them. At first, I could not approach a great man without trembling. |

I never felt my utter insignificance till, with uncovered head and downcast eyes, I stood in the presence of those renowned statesmen and orators whose names I had learned to revere. I was not so young, however, but that I could soon see into the hollowness of political distinction; the small trickery practiced in the struggle for power, the overbearing aristocracy of station, and the heartless and selfish intrigues by which public men maintain their influence. I became thoroughly disgusted with so much hypocrisy and bombast. It required no sage monitor to convince me that true patriotism does not prevail to a very astonishing extent in the hearts of those who make the most noise about it. The profession I had chosen enabled me to see behind the scenes and study well the great machinery of government, and I can not say that I saw a great deal to admire. Such life had no attractions for me. I looked forward with anxiety to the close of the session. There was one matter, about which I began to feel very uneasy – my contemplated visit to Europe. Where were the funds to come from? As yet, I had received from the sources upon which I had based my calculations barely enough to defray my expenses. Alas for my grand tour! "The best-laid plans of mice and men gang aft agley." Among my acquaintances was a young man from Ohio, who had temporary employment in the Treasury Department. Gifted with a fine intellect, and |

of most accomplished and engaging manners, he was just such a person as I had often wished to have as a companion. We first met at a social soiree; and in a very short time I found that he was a man after my own heart. A strong friendship sprang up between us. We visited together, disclosed our feelings and plans to each other, spent all our leisure hours in pleasant conversation, and resolved at length to travel together, if we could contrive some means to raise a sufficient sum. W––, unfortunately, was poor like myself. The summer was now well advanced, and we agreed it should not close before our departure, even if we should be reduced to the necessity of performing our grand tour on foot. The latter, it is true, was rather a rash determination, considering we were not gifted with the power of the Israelites, who walked across the Red Sea. For the purpose of enjoying our prospects without interruption, we spent every fine evening in the Capitol Garden, where, inspired by the moonlight, flowers, shrubberies, and murmuring fountains, we talked of the various surprising things we were going to do; how we would fall in with some extraordinary chances during our travels, make our fortunes, marry a couple of Arabian princesses, and return home to enjoy our good luck in peace, and excite the envy and admiration of mankind with accounts of our brilliant exploits. This was all very fine, and I hope it will not escape the reader's memory. |

Near the close of the session, finding my expenses and profits were nearly balanced, I resolved to remain no longer in Washington. My enthusiastic friend was ready to start with me at a moment's notice. Our minds were soon made up as to the route and means. We were to work our way to Europe, and, once there, depend upon our own wits for success in the pursuit of our object. We were very enthusiastic in the belief that energy and perseverance would overcome all the obstacles that poverty might throw in our path. I well remember the night previous to our departure. It was that of the 4th of July. After the usual ceremonies of the day, there was a grand exhibition of fire-works in the President's garden. A large concourse of citizens, visitors, members of Congress, and diplomatic characters, had assembled on the terrace of the Capitol to witness the brilliant and imposing scene. Some kind friend had circulated a report that we had received a commission from his excellency, Mr. Tyler, to arrange a matter of great national importance with the government of Portugal. The consequence was, that several of our distant acquaintances, who had formerly recognized us with a stiff nod, now crowded around us, and bid us good-by in the kindest manner imaginable, wishing us a most cordial reception at the court of Donna Maria. Having procured passports at the state Department, we took our departure in the cars early on the |

morning of the 5th of July, 1842. As it was not probable we could find a vessel in Baltimore bound for Europe immediately, we continued on to Philadelphia, where we spent a few days, and obtained some letters of introduction from a friend in the Custom-house to distinguished gentlemen in different parts of Europe. Finding no encouragement in Philadelphia for tourists with slender means, we proceeded to New York. Our joint purse on leaving Washington amounted to about forty dollars. Of course, we could not deny ourselves the gratification of` visiting the various places of public amusement; besides, being gentlemen up to that time, it was indispensable that we should patronize the best hotel, ride in an omnibus or hack whenever we did not feel disposed to walk, and be liberal with servants and porters. At the expiration of a few days, it alarmed us to find that we had but eight dollars left. Upon application for temporary employment, with a view to replenish our means, we learned that business was very dull, and young men were glad to avail themselves of the privilege of passing their time usefully in mercantile houses without remuneration; a species of amusement not particularly adapted to our circumstances. With due humiliation, let it be told; we were soon reduced to the necessity either of writing to our friends for a remittance, or of being insulted with an invitation to depend upon the charity of casual acquaintances. The first was out of |

the question; it would destroy ou diplomatic reputation; the last was too galling to our pride to be entertained for a moment. In this dilemma we strolled down to the shipping, and went on board a vessel bound for Bremen. The captain, a jolly-looking Dutchman, sat upon the companion way smoking his pipe, while he kept his eye upon some of the crew who were at work on the main deck. He received us very kindly, and gave us much information on the subject of seafaring life. It would be a difficult matter, he said, for two young men dressed as we were to procure employment on board a merchantman as light hands; but if we put off our "long togs," and went to work in a corn field for about three months, to give us a hardy look, we might succeed. Where there were upward of four thousand seamen idling about the wharves, it would be no easy matter for "green landsmen" to make a voyage. On the whole, he gave us rather an unfavorable idea of the life of a sailor, and advised us to try something else. He thought it a pity that young gentlemen of education should waste their time in a pursuit so little adapted to their physical strength. There were rough fellows enough in the world who could do that sort of work better than persons who had been delicately raised. The words of the kind-hearted old skipper made a deep impression upon our minds, and, if it were not for sheer shame, and the pressing nature of our |

circumstances, we would have abandoned our romantic notions at once. However, we felt that we were in for it, and it would not do to back out. W––, who was a printer by trade, had made several applications at the printing-offices for employment, but without success. Nothing, therefore, remained for us but the prospect of getting something to do on board a ship. It made no material difference to us in what capacity we went; all we desired then was to take leave of New York. The rest of that day and part of the next we spent in making inquiries at the ship agencies along the wharves; but our appearance, combined with our anxiety to become sailors, excited suspicion, and the answers were so unsatisfactory that we began to despond. I noticed that the old tars, who were lounging in groups about these offices, smoking their pipes, and chatting in a nautical style of language totally incomprehensible to us, eyed us slyly, and winked at each other as we passed. In the course of a few months we very well understood what they meant. There was something of novelty in being thrown upon our own resources in at large city, without a single friend to whom we could look for aid. still, as our money was spun out to a few dollars, it became necessary to leave off romancing, and bring our ideas down to the level of our circumstances. As we strolled along one of the wharves, casting wistful glances at the vessels close by, and now and |

then taking a peep into the shipping-offices, our attention was attracted by a slip of aper over a door bearing the following important intelligence: "WANTED IMMEDIATELY!!!

"Six able-bodied landsmen, to go on a whaling voyage from New Bedford. Apply up stairs before 5 o'clock P.M." This was somewhat encouging. Indeed, we thought it peculiarly lucky. It suited us exactly. We stopped and read the words over half a dozen times, in order to satisfy ourselves that we were not mistaken as to their import. But here was the difficulty: the notice said able-bodied landsmen. Were we of that description! We consulted the matter for some time, and at last came to the conclusion that light-bodied, active men, with a considerable share'of spunk, ought to succeed as well as heavy-built men. We accordingly entered the office with a bold, independent air, as much as to say, we knew what we were about. An excessively polite old gentleman of prepossessing appearance received us with every manifestation of cordiality. In answer to our inquiries concerning his notice, he replied: "Yes, gentlemen, I want a few more men. Do you think of shipping?" "Why, yes, we have some notion of it." "The very best thing you can do; sorry you are not a little stouter; but no matter, I think you'll answer the purpose. I just received a letter this morn- |

ing from Mr. ––, the whaling agent in New Bedford, requesting me to send on two light, handsome fellows. He don't care so much about their weight, if they're good-looking; wants them for a small vessel, you see, and likes to have a nice crew." "Well, you think we'll do?" "Oh!, no doubt about it. I'm willing to risk you, though I may lose something by it. Whaling, gentlemen, is tolerably hard at first, but it's the finest business in the world for enterprising young men. If you are determined to take a voyage, I'll put you in the way of shipping in a most elegant vessel, well fitted: that's the great thing, well fitted. Vigilance and activity will insure you rapid promotion. I haven't the least doubt but you'll come home boatsteerers. I sent off six college students a few days ago, and a poor fellow who had been flogged away from home by a vicious wife. A whaler, gentlemen," continued the agent, rising in eloquence, "a whaler is a place of refuge for the distressed and persecuted, a school for the dissipated, an asylum for the needy! There's nothing like it. You can see the world; you can see something of life!" The enthusiastic advocate of whalers then handed us a paper, which we immediately signed without reading, not wishing to give him time even to reflect upon his bargain. Promising to be at the office by half past four, we took leave of our worthy friend, and warmly congratulated each other upon having accidentally met with this benevolent old |

gentleman, who not only smiled upon the indiscretions of youth, but forwarded all our plans, and seemed ready to oblige us in every way. From a man whom we had never seen before, all this was certainly very gratifying. At five o'clock on the same evening we took a passage in the Cleopatra for Providence. In order that particular attention might be a paid to our comfort – as we supposed, but in reality to prevent our escape – we were consigned to an officer on board the boat. The agent also, to enhance our enjoyment, sent with us a couple of entertaining fellows, rather rough to be sure, and not very respectable in their appearance, bound on the same delightful mission. For all this we felt exceedingly grateful to our benevolent and venerable friend. It is true, we discovered after we got to sea that he had forwarded a bill of ten dollars to the New Bedford fitter, to be placed on our account with the owners. As we had sold one of our trunks, and some other unnecessary articles, the proceeds of which enabled us to pay our own expenses, we could not clearly see what this was for; but it occurred to us, after a great deal of deliberation, that it was a kind of bounty allowed by the city council to the agent for disposing of all vagrants who came within his reach, and that he had, through the force of habit, or in the confusion of his multifarious duties, mistaken us for persons of that description. On our passage to Providence, the steam-boat |

touched at Newport, where one of our whalemen, who had made a raise of three dollars from the New York agent – in remembrance, he said, of a whaling voyage on which the old gentlemen had sent him a few years previously – privately notified us of his intention to, "visit some of his friends up town." Not deeming the matter within our cognizance, we left him to pursue the bent of his inclination. We afterward had occasion to admire the sagacity, though not the moral obliquity of this fellow. Before parting from him, he gave us his experience as a whaleman, and advised us not to be gulled by fair promises. He said he knew a thing or two about it; that he would sooner be in the penitentiary any time; and, if we had any regard for ourselves, we ought to turn our backs upon New Bedford, for it was the sink-hole of iniquity; that the fitters were all blood-suckers, the owners cheats, and the captains tyrants. This was another damper. The warning made a deep impression upon us, and we often thought of it when at sea. We arrived in New Bedford without suffering more than the usual wear and tear to which all articles of traffick consigned from one sea-port town to another are subject. |

CHAPTER II.

I have not the conscience fo pass over in silence the disinterested generosity of the New Bedford fitter. His benevolence surpassed even that of the amiable old gentlemen in New York. When we first presented ourselves for inspection, he was a little bluff, to be sure, but that was only one of his good-natured peculiarities. "Why," said he, surveying us with professional deliberation, "you are not the men I wrote for. I want stout, hard-fisted fellows, who ain't afraid to work. Such slim chaps as you won't do at all!" "That's rather hard, sir; here we are without the means of getting back; and now, after the New York agent telling us you would take us, you say we won't do." What do I care about the New York agent?" replied the fitter. "It's his own look-out, and yours, if he don't send proper men. I'm not bound to take you at all; and I won't take you, if I don't like." "Well, you'll pay our expenses back, then?" At this the fitter laughed very heartily. |

"No, no, my good fellows; can't do that. I see you don't understand this business. What do you weigh?" We gave him our weight, but it did not seem to satisfy him exactly. He shook his head with a doubtful look, as much as to say he had no great respect for men who did not weigh considerably over our standard. He then punched us with his fist, shook us by the arms, and, after some farther experiments by way of testing our muscular powers, told us what there was of us was pretty good, "but there wasn't enough. Directing us next to walk up and down his long store-room, he planted himself against a pile of boxes, and watched our gait with the practiced eye of a jockey about to make a speculation in horse-flesh. Apparently satisfied, be ventured the opinion that we might do; at all events, he would exert his influence in our behalf with the owners. A clerk who sat in the counting-room, blowing his very soul through a cracked fife, was then directed to show us to old Captain R––'s boarding-house. Here we found a most jovial company; not very select, but remarkably free and easy. Among others, I recollect Red Sandy, Blue John, Long-legged Bill, Big-foot Jack, Chaw-o'-tobacco Jim, Handsome Tom, and one of our steam-boat acquaintances, who had already obtained the soubriquet of Bully Clincher; besides four lively house-maids, whom the sailors called Mag, Moll, Bet, and Peg, and with whom they seemed to be on the most friendly terms. |

Our fellow-boarders, when the fact became known that we were about to go to sea, entertained themselves with sundry jests at our expense, all of which we took with the utmost good humor. This completely disarmed them. We were shrewd enough to suspect their object, which, as we afterward learned, was to get us angry, and then, according to custom, give us a sound drubbing. Sailors have an inveterate dislike to young sprigs, who, when placed upon a level with them, assume airs of superiority. By guarding against this, we became great favorites. I must not omit, however, to mention one of the initiatory movements. While standing at the door, the first evening after our arrival, we overheard the comments made upon ourselves and our mission. "I say, Bill," said one, "there's a pair of bloody tars for you! They'll be slushin' down the t'gallant mast before long, or I'm out o' my reckoning." "Ay, ay, replied Bill; "better they never was weaned, than go driftin' round the world in a blubber hunter." "Never mind," added another, " they'll wish themselves in the watch-house before two months." With these and other remarks of the kind they amused themselves for some time, when one of the party, a regular old sea-dog, with a tremendous quid of tobacco in his cheek, waddled up to us, and, staring us in the face, exclaimed, "Well, cuss me if these ain't the lob-lolly boys wot sarved in one of my ships. I say, my lads, don't you |

know your old skipper? I'm Captain Bill Salt, wot used to larn you Lunars. Don't you know me?" "No; you must be mistaken. We have never been to sea." "Now I'm shivered if that ar'n't strange!" cried Captain Bill Salt; "if you ain't my lob-lolly boys, I never seed 'em." "Nevertheless, we are not. B–– is my name, and W–– is my friend's." "Well, just as good. You was both born to go to sea. Come, let's splice the main brace. Come along, shipmates! I'm agoin' to give these 'ere young gentlemen the first lesson in Lunars." Captain Bill Salt's manner was, to say the least of it, very friendly. We thought it best not to refuse his polite invitation. The sailors followed their comrade, who led the way to a chop-cellar a short distance from the boarding-house. "Come, all hands, what'll you take? Don't be shy. What d'ye say, shipmates," addressing W–– and myself; "close-reef or sea-breeze?" "Close-reef, said we, at a guess. "Bravo!" cried Captain Bill, grasping each of us by the hand; "you'll see the stars yet! If you ain't sailors, it's the 'fects of eddecation or s'ciety, wot's all the same. Come, here's a toast 'Be cheery, my lads! may your hearts never fail The toast was duly honored; and we discovered when we emptied our glasses, that "close-reef" |

was something very strong. Big-foot Jack, Chaw-o'-tobacco Jim, handsome Tom, Red Sandy, and the rest of our jolly friends, then seated themselves and called for cigars. Captain Bill Salt told us to do likewise; and, taking out his pipe, he soon enveloped himself in a comfortable cloud of smoke. Without waiting for the ceremony of an invitation, he gave vent to the following ditty, a copy of which I afterward procured from him: "PARTING MOMENTS.

"Farewell, my lovely Nancy, This song elicited the most rapturous applause. Captain Bill then spun us some tough yarns, while the company slipped out one by one. As we were about to leave, the bar-keeper called us aside, and |

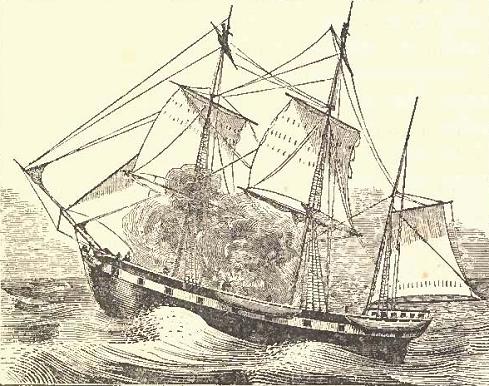

politely requested my friend and myself to pay the reckoning, assuring us that it was customary, when young gentlemen were about to go on a voyage, to treat all hands. We accordingly gave him our last cent, and were not a little edified at the cool manner in which Captain Bill Salt witnessed the operation. Though our confidence in that eccentric individual was a little shaken, we took the whole proceeding as a very good joke, and laughed to think how cleverly we had been gulled. Thus ended our "first lesson in Lunars." Our friend, the fitter, was a most accommodating man. With a delicate appreciation of our pecuniary embarrassments, he paid our board, furnished us with every little luxury we wanted, lent us his pleasure-boat to sail in, told us he would make our expenses all right with the owners, and gave us a great deal of fatherly advice about our conduct at sea. In addition to all this kindness, he considerately provided us with chests and sea-clothes at a terrible sacrifice, being at least ten per cent. cheaper than we could get them elsewhere. Besides, the mere fact of his crediting total strangers seemed so generous, so confiding, so high-minded! The only vessel about to sail immediately was the barque styx, * of Fair Haven. Through the exertions of our excellent friend, the fitter, the owners, * Some of the incidents related in this narrative render it advisable that I should mention no real names, except where the parties can not take offense. |

apparently with great reluctance, areed to take us. They told us the vessel was well fitted; better, in fact, than any vessel we could find. One of them, an old Quaker, assured us no whaler had ever sailed from New Bedford or Fair Haven as well fitted; he had attended to it all himself and, we might depend upon it, we would live in style. The captain, we learned from them, was a young man, pretty strict in his discipline, but a fine, generous fellow. He would treat us well, and give us plenty to eat; and, if we made ourselves useful, he would he very kind to us. He was a first-rate whaleman, and no doubt we would make a good voyage, and come home in a year or a year and a half with lots of money due to us. The vessel was a hundred and forty-seven tons burden, and calculated to hold a thousand barrels of oil. We were to receive the ordinary lay of green hands, being, as we were told, the one hundred, and thirtieth part of the oil taken. There was provision enough on board to last for twenty-seven months, so that, if not successful, there was no danger of our starving. We were to have what clothes we needed out of the slop-chest at the New Bedford prices. The shipping articles were then presented to us, and we signed them without exhibiting any such ungentlemanly want of confidence in the representations of the owners as to read the contents; besides, we were afraid, as they had accepted us so reluctantly, some difficulty might arise by which we would be deprived of the pleas- |

ure of performing a voyage under such pleasant auspices. The signing of the articles we regarded as a sort of security. With sapguine hopes and enthusiastic dreams of adventure we bade good-by to our New Bedford friends, and, on the morning of July –, embarked. The styx lay in the middle of the Acoshnet River, opposite the town of New Bedford. At 2 P.M. all hands were called to the windlass, and we weighed anchor. A light breeze slowly wafted us out into Buzzard's Bay. The shipping at the New Bedford wharf became gradually indistinct, and the houses looked misty in the distance. It was a beautiful Sabbath afternoon. The church bells were tolling a melancholy farewell; and I shall never forget the look W –– gave me as he pointed to the receding shores, and observed, in a melancholy tone, "I have unhappy thoughts. It seems to me those familiar sounds call us back. But we are too late; it is useless to repent now." My feelings were touched; the whole past was before me in a moment: friends, brothers, sisters, all! I would have given all I ever hoped to possess to retrace a few hours of my life. "Too late – too late! how heavily that phrase |

CHAPTER III.

Toward evening he captain came on board in a pilot-boat, and took charge of the vessel. I had not seen him before, and of course felt a curiosity to know what sort of a looking man he was. The owners had spoken in such glowing terms of him that, I must confess, he did not altogether realize my expectations. His personal appearance was any thing but prepossessing. Picture to yourself a man apparently about thirty-five years of age, with a hooked nose, dark crop hair, large black whiskers, round shoulders, cold blue eyes, and a shrewd, repul- sive expression of countenance; of a lean and muscular figure, rather taller than the ordinary standard, with ill-made, wiry limbs, and you have a pretty correct idea of Captain A––. He wore a broad-brimmed Panama hat, turned up at the sides, a green roundabout, a pair of dirty duck pantaloons, very wide at the bottom, and slip-shod shoes, which had evidently done service for two or three voyages. He walked the quarter-deck with his hands in his pockets, his eyes down; and his lips firmly compressed. Altogether he had a sneaking, hang-dog |

look that was not very encouraging to those destined to be subject to his will during a year's cruise, or perhaps longer. When he gave orders, it was in a sharp, harsh voice, with a vulgar, nasal twang, and in such a manner as plainly betokened that he considered us all slaves of the lowest cast, unworthy of the least respect, and himself our august master. Night closed upon us with rough and cloudy weather. By morning we had a heavy, chopping sea, and began to experience all the horrors of seasickness. The mate, a stout, bluff-looking Englishman, with a bull neck, kept us in continual motion, and gave us plenty of hard work to do, clearing up the decks, bracing the yards, stowing down the loose rubbish, and otherwise making the vessel tidy and ship-shape. He bellowed forth his orders to the men in the rigging like a roaring lion, yelled and swore at the "green hands" in the most alarming manner, and pulled at the ropes as if determined to tear the whole vessel to pieces. The loungers or "sogers" had no chance at all with him; he actually made them jump as if suddenly galvanized. For the sea-sick he had no sympathy whatever. "stir yourselves; jump about pull, haul, work like vengeance!" he would say, in the bluff, hearty voice of a man who appeared to think sickness all folly; "that's the way to cure it. You'll never get well if you give up to it. Tumble about there! Work it off, as I do!" To the haggard, woe-begone landsmen, who stag- |

gered about groaning under their afflictions, this sounded very much like mockery. For my part, I thought the mate a great monster to talk about sickness, with a face as red as a turey-cock's snout. After a day of horrors such as I had never spent before, we were permitted to go below for the night. Our condition was not improved by the change. The forecastle was black and slimy with filth, very small, and as hot as an oven. It was filled with a compound of foul air, smoke, sea-chests, soap-kegs, greasy pans, tainted meat, Portuguese ruffians, and sea-sick Americans. The Portuguese were smoking, laughing, chattering, and cursing the green hands who were sick. With groans on one side, and yells, oaths, laughter and smoke on the other, it altogether did not impress W–– and myself as a very pleasant home for the next year or two. We were, indeed, sick and sorry enough, and heartily wished ourselves ashore. Nothing can be more bewildering to a youth, whose imagination naturally magnifies all the dangers of the deep, than to be roused up in the dead of night, when the ocean is lashed into a fury by a stiff gale, the vessel pitching and laboring, and the officers yelling at the men as if endeavoring to drown the roaring of the elements with loud, fierce imprecations, while thick darkness enshrouds all – darkness so dense, that, but for momentary flashes of lightning, one might fancy chaos had come again. Such was the novel and startling scene that burst |

upon us with all its wildness on the night of the 19th. "We were dead of sleep, Sea-sick and harassed after a hard day's work, we had gladly availed ourselves of a few hours' respite from duties so laborious. The mate came to the scuttle, and, with half a dozen tremendous raps, roared at us to bear a hand. "Tumble up, every mother's son of you, and take in sail. Out with you, green hands and all. We won't have any sick aboard here. You didn't come to sea to lay up. No groaning there, or I'll be down after you. D'ye hear the news down below? Tumble up! tumble up, my lively hearties!" There was no refusing so peremptory a command as this, little as we liked it. Without exactly tumbling up, we contrived, with some difficulty, to gain the deck, for the vessel pitched so violently that few of the green hands could keep their feet under them. I shall never forget the bewilderment with which I looked around me. We were in the Gulf stream, enshrouded in darkness and spray. The sea broke over our bows, and swept the decks with a tremendous roar. Momentary flashes of lightning added to the sublimity of the scene. When I looked over the bulwarks, it seemed to me that the horizon was |

flying up in the clouds and whirling round the vessel by turns, and the clouds, as if astonished at such wild pranks, appeared to be shaking their dark heads backward and forward over the horizon. I looked aloft, and there the sky was sweeping to and fro in a most unaccountable manner. The vessel went staggering along, creaking, groaning, and thumping its way through the heavy seas. I grasped the first rope I could get hold of, and held on with the tenacity of a drowning man. For a few moments I could do nothing but gasp for breath, and wipe the salt water out of my eyes with one hand while I held on with the other. The confusion of voices and objects around me, the tremendous seas sweeping over the decks, and the flapping of the sails, impressed me with the belief that we were all about to be lost. I kept my grasp on the rope, thinking it must be fast to something, and, if the ship foundered, I should at least be sure of a piece of the wreck. As for my comrade W–– , I supposed he was still on board, and called for him with all my might, but the wind drove my voice back in my throat. While standing in this unpleasant predicament, the mate came rushing by, shouting to the green hands to "tumble up aloft, and lay out on the yards!" Aloft such a night, and for the first time! Was the man mad? The very idea seemed preposterous. Presently he came dashing back, thundering forth his orders with the ferocity of a Bengal tiger. "Up with you'. Every man |

tumble up!' Don't stand gaping like a parcel of boobies! Aloft there, before the sails are blown to Halifax!" Knowing how useless it would be to remonstrate, and believing I might as well die one way as another, I sprang up on the weather bulwark and commenced the terrible ascent. The darkness was so dense that I could scarcely see the ratlins, and it was only by groping my way in the wake of those before me, that I could at all make out where I was going. A few accidental kicks in the face from an awkward fellow who was above me, and a punch or two from another below me, convinced me that I was in company, at all events. How I contrived to drag myself over the foretop, I do not well remember. By a desperate exertion, however, I succeeded, and holding on to every rope I could get hold of with extraordinary tenacity, I at length found myself on the foot-rope, leaning over the yard, and clinging to one of the reef-points, fully determined not to part company with that in spite of the captain, mate, or whole ship's company. "Haul out to leeward!" roared somebody to my right; "knot away!" This was all Greek to me. A sailor close by good-naturedly showed me what I was to do, and having knotted my reef-point, I looked down to see what was the prospect of getting on deck again. The barque was keeled over at an angle of forty-five degrees, plunging madly through the foam, and I could form no idea of the bearings of the deck. All I could see was a long dark object below, half hid- |

den in the raging brine. My right-hand neighbor gave me a hint to get in out of the way, which required no repetition, for I found my situation any thing but pleasant. By the time I reached the foretop my head was pretty well battered, and my hands were woefully skinned and bruised, the sailors having made free use of me to acelerate their downward progress. I found, on gaining the forecastle, that my friend W–– had passed throngh the ordeal in safety. We said nothing, but looked our unqualified disapprobation of such a life. Thee Portuguese, to make matters still worse, laughed heartily at the sorry figure we cut, and told us all this "was nothing to what we'd see yet." Next day the green hands, including my friend and myself, looked haggard enough. We were all dreadfully sea-sick. Our fare was by no means inviting under such circumstances. For breakfast we had an abominable compound of water, some molasses, and something dignified by the name of coffee, with hard biscuit and watery potatoes; for dinner pork, salt beef, and potatoes; and for supper, a repetition of the biscuit and potatoes, with boiled weeds and molasses as a substitute for tea and sugar. It was perfectly amazing the voracity with which the Portuguese devoured this fare. Had they whetted their appetites for months on raw corn they could not have swallowed such food as was now before them with more relish. I must confess, their digest- |

ive powers excited my envy as well as my astonishment. It made me despair to see them eat. I would have given all I expected to make during the voyage to possess their swinish relish for food. However, before the expiration of two months, I had reason to change my tune. I would have given twice as much to get rid of my appetite! We had on board a Yankee boy, who afforded much amusement to the crew. MacF––, or, as he was called for shortness, Mack, was a down-east chap from "away up Maine," somewhere in the neighborhood of sunrise. Had Nature been in her most whimsical mood, she could not have formed a greater curiosity than Mack, in every respect. He was an odd specimen of the "live Yankee." Imagine a gawky youth of nineteen, with arms reaching down to his knees, tremendous wrist bones and hands, a lank visage, shins like drum-sticks, and feet moulded for a giant, but placed by mistake under the aforesaid shins, and you have a fair representation of his outward man. Mack, notwithstanding these freaks of Nature, was a general favorite. Nothing could ruffle his good humor. His awkwardness and quaint wit were irresistible. I doubt if Yankee Hill or Dan Marble ever had a better model. Mack was woefully sea-sick. The poor fellow's face was the very picture of sorrow. His skin, naturally dark, had assumed a greenish hue, and his lank cheeks and protruded lips formed a most pathetic picture of rueful retrospection. Sick as I was my- |

self, I could not repress my risables, when, leaning over the monkey-rail, squaring accounts with old Nep, he paused every moment to exclaim, "There! durn it all, I know'd I was goin' to be sick. Oh, gosh! oh, gosh!" Poor Mack! From the bottom of my heart I sympathized with him as he groaned, "Dod burn the thing! I wouldn't grudge twenty dollars if I was at hum milkin' the keows." "Why, Mack," I inquired, "you are not tired of whaling already, are' you?" "Well, I can't say, exacly; but I guess this child won't be caught in such a snap agin; not soon he won't. Oh, gosh! gosh! Dod blame the luck! 'Tain't no use to try; folks says salt water helps it some, but, durn the thing, I've swallered a bucketful, an' I feel a devilish sight worse an' ever." "Maybe you haven't swallowed enough, Mack," said the cook; "try another bucketful, and, likely as not, it'll cure you." "No, I won't!" retorted Mack; " cause, durn the stuff, 'twarn't never made for nothin' in human shape. I wish I hadn't never seen a drop on't. Salt water! Ugh! Oh, gosh! oh, gosh!" "What induced you to ship on a whaling voyage?" I asked, forgetting my own folly. "Why didn't you stay at home, Mack, where you were better off?" "Well, I don't know. I came because I was a dod-burned fool; an' I s'pose you hadn't no better |

reason. Nobody hadn't oughter leave hum. Folks that be hum can't do better than stay thar." I made no farther attempts to be witty at Mack's expense on this occasion. CHAPTER IV.

Among the foremast hands was a man from Charleston, South Carolina, by the name of Smith. According to his own representation, he had served as steward in some of the schooners running from Charleston to New York. He professed to be well acquainted with ship duties, and his name was down on the papers as ordinary seaman. A boy from Fall River, who had shipped as steward, was so sea-sick as to be unable to do duty. The captain sent the mate forward to procure a temporary substitute from among the crew. Smith was selected, and ordered aft to act as steward until the recovery of the boy. He resolutely refused to act in that capacity, stating that he had shipped as an ordinary seaman, and would remain before the mast. The mate, upon reporting his refusal, was sent forward to make him turn out at all hazards. Smith was very ill at the |

time, and the mate, not wishing to be hard with him, did not resort to force. No threats, however, had any effect upon him. He steadily refused to act as steward, and stated, moreove that he was unable to do duty of any kind, and would not be forced on deck until sufficiently recovered from his illness. The captain then came forward to the scuttle, and called upon him, in a peremptory voice, to turn out. "I'm sick; I'll not go on deck!" said Smith. "Won't you? I'll soon make you!" shouted the captain. "I'll see whether you will or not!" Springing down the ladder, he then grasped Smith by the shirt-collar, and dragged him out of his berth. "Up with you, now, and not another word from you!" "No, sir, I'll not go on deck," said Smith, making a show of resistance. "You'd better mind how you handle me! I'm a Charleston man, myself! Let me go; let me go, sir!" "Are you, hey?" thundered the captain; "a Charleston man? I'll let you know what I am; I'll let you know that I'm captain of this ship!" With these words the captain dragged him up the ladder by main force, and, jerking him through the scuttle, collared him against the foremast. Faint and haggard with sickness, the offender commenced pleading for mercy. "Don't choke me, captain; don't choke me!" "Yes, I'll choke the stubbornness out of you; I'll choke obedience into you!" roared the captain, shaking him by the throat. |

Great God! you'll kill me," groaned the man, nearly black in the face. "Do your duty, then." "I will, sir, I will. Don't kill me." "Go aft, then, and act as steward till I think proper to get one in your place; and remember, if you show any more of your stubbornness, I'll flog it out of you with a rope's end." Smith staggered aft, rubbing his throat, and crying with pain. From that time forth he was the officers' dog. He had earned a bad name for himself, and he kept it during the remainder of his stay on board the vessel. This was the commencement of trouble. It was deemed an appropriate occasion to "lay down the law." All hands were called aft. The captain deliberately stalked the quarter-deck, exulting in the "pomp and circumstance" of his high and responsible position. Every step he took be spoke the internal workings of a man swelling with authority. The proud glance of his eye; the severe frown-of his heavy eyebrows; the haughty curl of his lip; even the peculiar twist of his long, nasal protuberance seemed to say, "Behold, and wonder! I stand before you arrayed in a halo of glory. I am commander of the great barque styx! Authority is mine! Look upon me, all ye who have eyes to see, and tremble, all ye who have ears to hear!" With his hands stuck in his breeches pockets, he then approached the break of the quarter-deck, and, strad- |

dling out his legs to guard against lee-lurches, asked if all hands were present. One of the officers replied in the affirmative. The scene was at once grotesque and impressive. Fourteen men, comprising he whole crew, were huddled together in the waist, at the starboard gangway. Of these four were Portuguese, two Irish, and eight Americans; and certainly a more uncouth-looking set, including my friend and myself, never met in one group. The Portuguese wore sennet hats with sugar-loaf crowns, striped bed-ticking pantaloons patched with duck, blue shirts, and knives and belts. They were all barefooted, and their hands and faces smeared with tar. On their chins they wore black, matted beards, which had apparently never been combed. The color of their skin was a dark, greenish-brown, if the reader can imagine such a color, and was calculated to create the impression that they never made use of soap and water. The variety of dress in which the rest of the crew were habited was fully as striking as that of the Portuguese. Some wore Scotch caps, duck trowsers, red shirts, and big horse-leather boots; others, tarpaulin hats, Guernsey frocks, tight-fitting cloth pantaloons, and red neckerchiefs. Several were bareheaded and barefooted; having lost, their hats and shoes in the late gale. All the green hands, which included most of the Americans and the two Irishmen, were still cadaverous and ghastly after their sea-sickness, and not more than two had yet entirely "squared ac- |

counts with old Nep." Altogether we were the most extraordinary looking set of half-sailor nondescripts possible to conceive. Thus situated, and thus equipped for sea life, we stood gaping at the captain in silent admiration. The mates and boat-steerers, consisting of the chief mate, an Englishman, the second mate, an American, two Portuguese boat-steerers, and an American of the same grade, stood near the mainmast, looking on with the air of men who were used to such things, and took no particular interest in them. The captain, after considerable deliberation, and a great show of contempt toward every body within range of his visual rays, then addressed is in a sharp nasal voice, fixing his eyes upon each man alternately. I had listened to many speeches, but never to one more pointed than this. No doubt he will be surprised to find it literally reported: "I suppose you all know what you came a whaling for? If you don't, I'll tell you. You came to make a voyage, and I intend you shall make one. You didn't come to play; no, you came for oil; you came to work." [Here he took a turn on the quarter-deck, and while concentrating his ideas for another burst of eloquence, amused himself in an undertone, partly addressed to himself individually, and partly to the mate, by letting us know that it should be "a greasy voyage, and a monstrous greasy one too."] "You must do as the officers tell you, and work when there's work to be done. We didn't ship you |

to be idle here. No, no, that ain't what we shipped you for, by a grand sight. If you think it is, you'll find yourselves mistaken. You will that – some, I guess." [Here he lost the idea, or, to use a more expressive phrase, "got stumpef."] "I allow no fighting aboard this ship. Come aft to me when you have any quarrels, and I'll settle 'em. I'll do the quarreling for you – I will." [Another turn on the quarter-deck.] "If there's any fighting to be done, I want to have a hand in it. Any of you that I catch at it, 'll have to FIGHT ME!" [A frightful doubling up of the fists, and a most ferocious gnashing of the teeth.] "I'11 have no swearing, neither. I don't want to hear nobody swear. It's a bad practice – an infernal bad one. It breeds ill will, and don't do no kind o' good. If I catch any one at it, damme, I'll flog him, that's all." [A nod of the head, as much as to say he meant to be as good as his word.] "When it's your watch below, you can stay below or for'ed, just as you please. When it's your watch on deck, you must stay on deck, and work, if there's work to be done. I won't have no skulking. If I see sogers here, I'll soger 'em with a rope's end. Any of you that I catch below, except in cases of sickness, or when it's your watch below; shall stay on deck and work till I think proper to stop you." [A stride or two aft, and a glance to windward.] "You shall have good grub to eat, and plenty of it. I'll give you vittles if you work; if you don't work, you may starve. Don't grumble |

about your grub neither. You'd better not, I reckon." [A mysterious shake of the head, which implied a vast deal of terrific meaning.] "If you don't get enough, come aft and apply to me. I'm the man to apply to; I'm the captain." [Here he surveyed himself with a look of exultation, which seemed to say that he was not only the captain – the very man to whom he had special reference, but that it was a source of infinite satisfaction to him to be the captain.] "Now, the sooner you get a cargo of oil, the sooner you'll get home. You'll find it to your interest to pay attention to what I say. Do your duty, and act well your part toward me, and I'll treat you well; but if you show any obstinacy or cut up any extras, I'll be d––d if it won't be worse for you! Look out! I ain't a man that's going to be trifled with. No, I ain't – not myself, I ain't! The officers will all treat you well, and I intend you shall do as they order you. If you don't, I'll see about it." [Three or four strides to and fro on the quarter-deck, and a portentous silence of five minutes.] "That's all. Go for'ed, where you belong!" Had the captain made good all his promises, we would have had no just cause for complaint; but we soon discovered that his speech was merely designed to intimidate us. From that time forth we had the poorest fare, and in the scantiest quantities. The owners had given us positive assurance that there never had sailed from that port a vessel better fitted in every respect. For their misrepresentations, we |

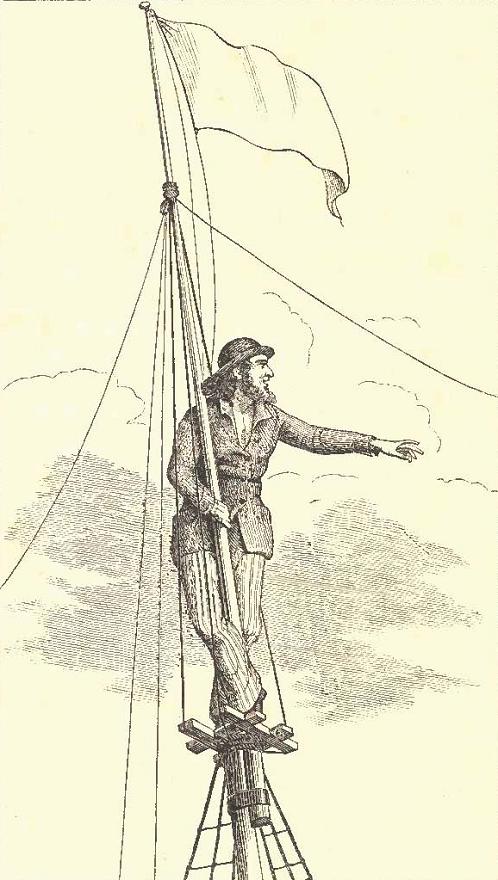

heartily wished them a berth in their own barque, believing that the severest punishment that could be inflicted upon them. A month's trial at it would make them exercise more humanity toward their fellow-creatures. Next in the routine of business was the choosing of watches. We were all called to the waist that evening, and examined like a parcel of bullocks about to be butchered. The mate and second mate made the selections. Among others, I was chosen for the larboard or mate's watch, and my friend for the starboard or second mate's watch. The watch on deck was then set to work on the whaling gear. Our duties from that time till we arrived on the western whaling ground were, working ship, grinding harpoons, spades, lances, boarding knives, &c., making deck brooms, washing decks every morning, clearing the rubbish away every afternoon, stowing away loose casks, steering and standing mast-heads. Whenever the weather was fine we lowered the boats and practiced at pulling, backing, and all the maneuvers necessary in the capture of a whale. All this severe labor was very hard upon those who had not been accustomed to great physical exertion. |

CHAPTER V.

Nothing of interest transpired after the difficulty with Smith, till July 27th. – I had afternoon watch below, and had turned in to forget my troubles in sleep. About two o'clock I was roused by the steward, who informed me that W–– had suddenly fallen upon the deck in a fit of convulsions. I immediately sprang up the ladder and ran aft. Language can not depict, the shocking spectacle that met my eyes. There was my bosom friend, sitting up against one of the scuttle-butts, his shirt open, his hat lying on the deck, and his eyes ready to start from their sockets. The captain stood by him, holding him by the hand. I felt sick and giddy, when W–– stared at me with the vacant gaze of an idiot. Bursting into a wild laugh, he attempted to spring up. It was a fearful laugh – a laugh that rang like a death-knell in my ears. I grasped him by the hand; the terrible thought struck me that he had gone mad! His voice was wild and unnatural, and his whole appearance awful in the extreme. Gazing vacantly in my face, he burst into tears, and sobbed as if his heart would break. I called him by name; I implored |

him to speak to me. Without noticing my appeals, he turned to the captain and inquired my name. Upon receiving an answer, he begged me, in the most piteous tones, to convey a message home to his mother, that he never should see her again. "Before another hour," he said, "I shall be food for the sharks. 0 God, must I die so soon? Am I never to see home again? I have kind, good parents; tell them I died thinking of them. It is horrible – horrible to be thrown overboard in a sack!" No effort to console him had the slightest effect. The fearful idea that he was about to be devoured by the sharks seemed to drive him mad. He raved of strange things which he had seen at the masthead; talked incoherently of birds with beautiful plumage, curiously-formed fishes, and called upon us wildly to save him from the sharks. It was a scene of horror that I shall never forget. When he became somewhat composed, one of the hands, assisted by myself, carried him forward to the forecastle, and laid him in his berth. For three hours he lay in a trance, with his eyes wide open, not moving a muscle. He looked like one that was dead. It appeared, from the statements of the watch on deck, that he had just come down from the masthead, where the rays of the sun poured down with an intense heat. On reaching the deck, he walked aft toward the captain, who was parading the quarter-deck. After passing the break of the deck he |

stood still, and while in the act of addressing the captain, fell down in convulsions. From all these circumstances, and from the fact that he was not subject to fits, it was quite evident that it was a sunstroke. He had suffered severely from sea-sickness, and was greatly debilitated. A burning sun beating down upon his head for two hours could very easily have produced the terrible effects described. I thought it very hard that a man, really suffering from illness, should be compelled by the captain to stand two hours a day at the mast-head. It was, in this case at least, little better than murder. W–– never recovered from the effects of this fearful affliction. Better, far better would it have been for him, had he fallen from his post and found a watery grave. There are things connected with this event that weigh heavily upon my heart; things not rudely to be touched – affections tried and hearts broken. It is needless to dwell upon his sufferings during the remainder of his stay on board the ship. The Portuguese were mere brutes, and, with two or three exceptions, the rest of the crew were little better. Sympathy for the sick was a weakness unknown to them. No temptation mould induce them to refrain from smoking, swearing, and blackguarding. I attempted to purchase peace by giving them my clothes, but my exertions were of no avail. I saw that it was useless to expostulate, and finding that the noise increased W––'s malady, I appealed to the captain to exert his influence over them. His |

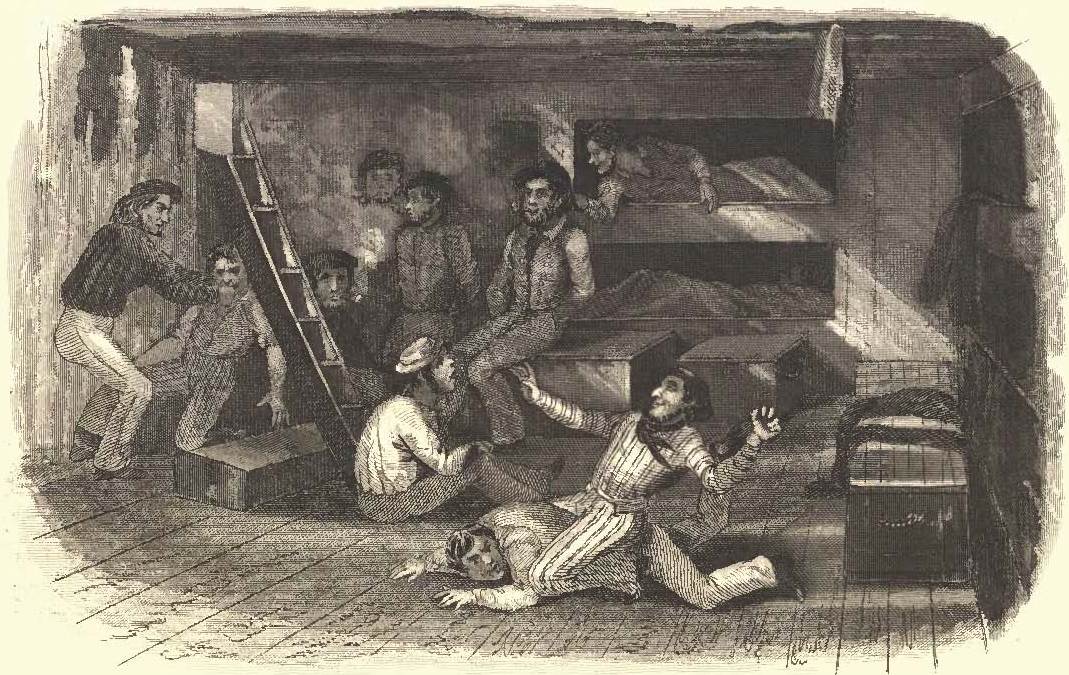

reply was characteristic, and just such as I might have expected had I known him better. "He had nothing to do with the forecastle. The Portuguese, as well as the Americans, were at liberty to do as they pleased in it. He had no control over them after they went below. W–– had no business coming to sea to get sick, and be a trouble to all on board. He had seen such fellows before, and would not put himself out of his way to pamper to their wants. Now that he was in a scrape, let him make the best of it, and not trouble folks with his complaints. If he wanted medicine, he might have it, and that was all that could be done for him." Where such an example was set by the captain, I could not expect the crew to do otherwise than follow it. For FIFTY-TWO days W–– lay in the forecastle, suffering such tortures of body and mind as can not be described. The captain gave him to understand that he should not leave the vessel the whole voyage; he might die in the forecastle, for what he cared. During all this time, my unfortunate comrade had nothing to eat but hard biscuit, and occasionally, a piece of butter about the size of a dollar; so reduced was he that nothing else allowed the crew would remain on his stomach. The hot, close atmosphere of the forecastle, rendered still more suffocating by the fumes of old pipes and bad cigars, was not very well calculated to promote his recovery. It would be difficult to give any idea of our fore- |

castle. In wet weather, when most of the hands were below, cursing, smoking, singing, and spinning yarns, it was a perfect Bedlam. Think of three or four Portuguese, a couple of Irishmen, and five or six rough Americans, in a hole about sixteen feet wide, and as many, perhaps, from the bulk-heads to the fore-peak; so low that a full-grown person could not stand upright in it, and so wedged up with rubbish as to leave scarcely room for a foothold. It contained twelve small berths, and with fourteen chests in the little area around the ladder, seldom admitted of being cleaned. In warm weather it was insufferably close. It would seem like exaggeration to say, that I have seen in Kentucky pig-sties not half so filthy, and in every respect preferable to this miserable hole: such, however, is the fact. In this loathsome den, the Portuguese were in their element, revelling in filth, beating harsh discord on an old viola, jabbering in their native language, smoking, cursing, and blackguarding. Their chief recreation, however, was quarreling, at which they were incessantly engaged. Nor was it confined to week-days, for not the slightest regard was paid to the Sabbath. The most horrible profanity was indulged in, and to an excess that was truly revolting. They did not seem aware even of the existence of a Supreme Being. And yet these Christians chattered a paternoster over their beads every night! What mockery! I asked Enos, the most intelligent of them, if he had ever read a book called the Bible. |

"No," said he, "I don't sabe how to read." "Did you ever hear of it?" "I don't know." "Do the people on the Western Islands pay any regard to Sunday?" "Oh yes. When Sunday come, dey go to chapel. In de morning dey pray, in the evening dey dance and play cards; dey have fandango. Old padre say dat bad; we say, here ten cent. Den padre laugh and say no more 'bout it." Here the Portuguese all set up a laugh, and commenced singing, in whining voices, "Dominus vobiseo;" &c. As soon as we arrived on the western whaling ground, boat watches were set. In a small vessel like the styx, with three boats, besides a spare boat aft, there are usually three watches, consisting of the larboard, starboard, and waist boat's crew. Each watch is under the command of a boat-steerer after sail is shortened, which is generally about sundown. In our watches there were four men, and the boat-steerer. The mate and second mate sleep all night, and remain on duty all day. The alternate hours of duty and rest with the crew are arranged thus: Say the larboard and starboard boat's crews go below after sail is taken- in; the waist boat's crew remains on deck till ten o'clock, when it is relieved by the larboard boat's crew, and turns in till the hands are called in the morning. The watch then on deck is relieved at one by the starboard boat's crew, which |

remains on deck till all below are called in the morning. The starboard watch then has forenoon watch below, the larboard the afternoon, and the waist boat's crew all day on deck. In making a passage, there are but two watches, the larboard and starboard, which are headed by the first and second mate, who take the same hours of rest allowed the crew. So much of my time was taken up at the helm and mast-head, that I had but few hours every day to devote to my unfortunate friend, who could look to me alone for aid. Each day he became more exhausted from want of proper nourishment and care. August 3d. – We had now prepared all the whaling gear, and were daily on the look-out for whales. August 5th. – The boats were lowered for black-fish. I took my place, for the first time, at the aft oar in the waist boat. After rowing about two miles, we came up with the school.* It was an unusually large one, but the day was so calm that they were very shy. We made several unsuccessful attempts to get a dart at them, and continued the chase for six or eight hours under a burning sun. I was pretty well tired of my oar by the time we turned toward the vessel. The Portuguese consoled me with the remark, that I bad not begun to see "a hard pull yet," and enjoyed my cadaverous looks with great satisfaction. * The term generally used by whalemen when speaking of a gang or company of whales or smaller fish. |

From seven till nine o'clock we usually spent on deck, amusing ourselves at the various pastimes common among sailors. When the weather permitted, we had dancing, singing, and spinning yarns. The Portuguese had a guitar, or viola, as they called it, with wire strings, upon which they produced two or three melancholy minors, accompanying their performance with a harsh, unmusical chant. Four of them formed couples, and while one of the by-standers played the guitar, those forming the set moved backward and forward like hyenas in a cage, pawing the deck with their feet, and using their fingers by way of castanets; all chanting, in a whining tone, two or three monotonous notes, which they repeated till it became fairly distracting. While the Portuguese amused themselves in this way, the American portion of the crew had songs, yarns, and dances after their own fashion. As all human enjoyments are comparative, so many an hour of real pleasure was thus passed on board the styx by myself and others, who had seen worse times since we had left New Bedford. |

CHAPTER VI.

I alluded, in the preceding chapter, to the difficulty with Smith as the beginning of trouble on board. Soon after that a disease of long standing attacked him, and confined him to the forecastle for some time. He was abused by the Portuguese, and hazed by the officers for not getting well. The captain, disappointed in procuring oil, became so morose that, for days in succession, he spoke not a kind word to any of the crew. He swore, one morning, that if Smith would not come on deck and go to work, he'd drag him out of the forecastle. Between the abuse of the Portuguese on the one hand, and threats on the other, Smith thought it best to attempt to go on duty; and the same evening he crawled up the ladder, and staggered aft, so weak that he could scarcely walk. In all vessels the invalids, who are able to do any thing, take the helm, which was the duty assigned to this man. The captain was sitting on the gunwale of the larboard boat, close by. It should be remarked that he had an inveterate ill will against Smith ever since the |

morning of the difficulty; and on several occasions observed, that he "might rot in the forecastle, and be d––d, before any trouble should be taken about such a worthless rascal!" I was in the waist at work grinding irons, when I was attracted by the harsh voice of the captain ordering him to "luff." Ignorant of the custom which requires the helmsman to repeat the order (for it appeared that he had never been to sea before), Smith put the wheel to leeward, supposing that to obey was sufficient. "Luff, I tell you, luff!" roared the captain, in a savage voice. "Do you hear, there?" Weak and nervous from the effects of his disease, the poor fellow continued to luff, muttering that she was coming up. "Luff! will you luff?" was the reply. Without any answer, Smith put the wheel hard down. "You scoundrel, luff!" thundered the captain, frantic with rage. "Do you hear me? you sheep-head, do you hear me?" "Yes, sir, I hear," said the man, quietly; and, indeed, it would have been difficult to avoid hearing, for the captain's voice was like the braying of an ass. "The devil take you, then, why don't you answer?" "I answered once, sir." "No, you didn't; don't tell me that! don't tell me that, I say. Now, I tell you to meet her." |

Smith obeyed, but made no reply. "Curse you! I'll teach you to answer! I'll flog the stubbornness out of you! You hear well enough; but it's your stubbornness!" With that the captain sprang down on deck, and, rushing upon Smith, struck him several times across the face with his open hand. Haggard and faint, the poor wretch clung to the wheel to avoid falling. "I'll whale the stubbornness out of you! I'll have you answer me when I speak to you. Now, when I tell you to do a thing, you'll do it;" and, with other polished expressions of the kind, he walked to and fro on the quarter-deck, chafing with rage. "How does she head?" next came, in a gruff voice. "East, sir." "You lie! you lie!" There was no answering such an accusation as this; for, if the captain says black is white, it must be so. "How does she head?" (louder and fiercer.) "East." "You lie! I tell you, you lie! Don't you lie to me! If I catch you lying, I'll warm you!" "She heads so, according to the compass." "Don't tell me that; I know better. You'll be larning me the compass next! Look sharp, there! I'll warm your back!" No doubt this treatment was intended to impress the man at the wheel as well as the spectators with |

a sense of awe toward the captain, and a proper respect for his authority and personal dignity. To me, however, there was something horribly brutal in it. I vowed in my heart he should be sorry for such cowardly conduct toward one who was unable to resent it. The time, I hoped, would come when I would have it in my power to show him that even a foremast hand may have feeling, and is not to be abused with impunity. This was but an everyday incident, after all. It may be that I have wasted time in describing it. I know there are some whose nicer feelings will revolt at such scenes. It should be borne in mind, however, that incidents of this kind form a great part of a sailor's life. To some readers, who derive their ideas of things aboard ship from sea novels, in which the valor of the heroes consists in a heroic contempt of all authority, and a superabundance of impertinence, it may seem that to submit tamely to the over-bearing bullying of a brute, without retort or resentment, shows a want of manly spirit. I would ask, what is to be done in such cases? A man has no right to strike his commander, however well justified he may be in so doing, according to our notions of right and wrong. Nor must he use language that can be termed insolent or mutinous. This might do ashore, where one man can meet another upon equal terms; but it can not be carried out at sea. If the captain can not manage Jack, the officers are ready to lend their aid; and, to my thinking, it would be |

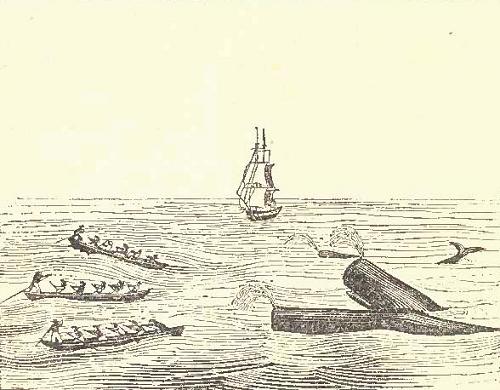

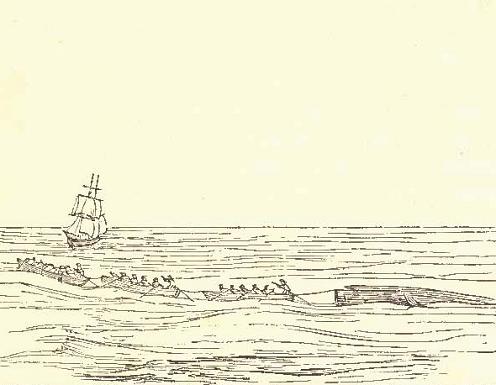

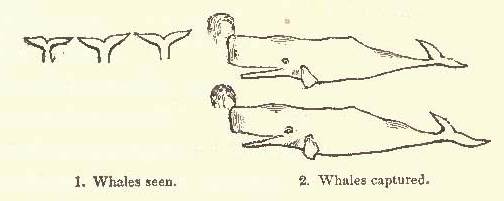

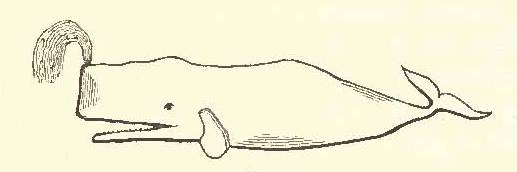

poor satisfaction to be seized up by main force and flogged like a negro. Until masters are taught, by the severest punishment, that their little brief authority does not justify them in acts of tyranny and cruelty, poor Jack must quietly submit to all his woes! August 16th. – Chased a school of whales all day. At 6 o'clock P.M. their spouts were seen about two miles off the lee bow. The larboard and starboard boats, headed by the captain and the mate, were lowered. At 10 P.M. the boats came alongside with a twenty-barrel whale in tow. All hands set to work rigging up the cutting tackle, and getting the try-works ready. The appearance of this, our first whale, was hailed by a general cheer. After the watches were set, and the decks cleared, I had an opportunity of examining our prize. It was about thirty-five feet in length, of a rather light color, and had a strong, disagreeable smell of oil. Though considered a very small whale, its proportions seemed gigantic enough to me. It was surrounded by sharks eagerly awaiting their prey. No correct. idea can be formed of the process of capturing whales and trying out their blubber, without some knowledge of the instruments employed. I shall take pains to make my information on this subject as intelligible as possible to the "unlearned" landsman, taking it for granted he is not versed in the mysteries of the craft. |

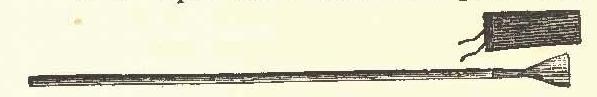

First in importance is the harpoon. This instru-

ment, called, in whaling parlance, an "iron," is generally between three and four feet long, with a bearded head, and a shaft or handle of hickory, oak, or dog-wood, about a foot longer than the iron, pointed at the end so as to fit in the socket of the harpoon. A strap, or piece of tarred rope, fastened to the pole and firmly woven over the socket, keeps them together, and forms a loop to which the tub-line is attached. The harpoon is the first instrument made use of in the capture of a whale. Instances, however, have occurred, in which whales have been taken by the skillful thrusts of a lance. In ordinary cases, only one harpoon is made use of, but should it "draw," or the whale prove difficult to manage, it is not unusual to dart three or four. Each boat is provided with that number. The head of the harpoon, when not in immediate use, is preserved from rust by a wooden cover, the inside of which is formed to fit it closely. It is the province of the boat-steerer to keep the whaling gear in good order, and he takes particular pride in the sharpness and polish of his "irons." The name of the vessel or captain is usually stamped on the thick part of the harpoon so that, in case of a dispute between two captains in relation to their right to a whale struck by both, the matter may be determined by reference to the |

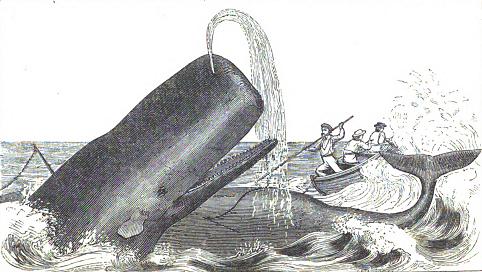

brand. The first fast harpoon, if still attached to the line in the boat, forms an indisputable right to the whole whale; but if the line be cut or broken, and the last save the loose whale, then the oil is equally shared, or the claimant yields his right by courtesy, or for a suitable consideration. The lance is somewhat longer than the harpoon,

without beards, and shaped at the head not unlike a spoon, but convex on both sides, and very sharp on the edges and at the point. The handle is perfectly straight and handsomely rounded, and varies from five to seven feet in length. A small line, about the thickness of a ratlin, is attached to it, for the purpose of drawing it back to the boat after a "dart" The lance is made use of to dispatch the whale, after having first secured him with the harpoon. When the whale becomes sufficiently quiet from exhaustion caused by exertion or loss of blood, the boat from which the harpoon has been darted draws up by the line, and the chief officer in command exchanges places with the harpooneer, being of a higher grade, and presumed to be more experienced in the business, and begins the responsible task of lancing. This is the most dangerous part of the contest. It is often difficult to get the boat in a favorable position, and a slight error of judgment, or a want of skill in the officer, may occasion the loss of the whole boat's crew. Two or three skillful darts |

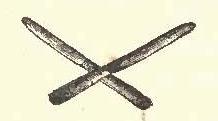

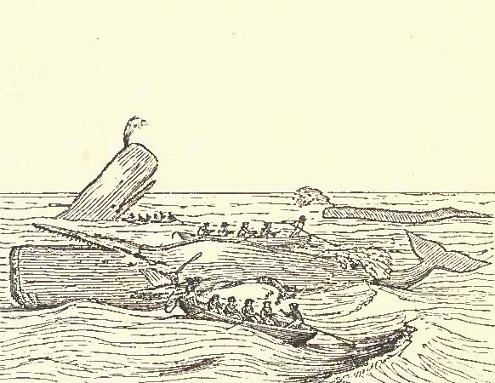

will bring the life-blood in a few minutes, and I have known cases in which, by a single well-directed dart, the whale was almost instantly killed. To strike a whale in the "life," or vitals, the first dart, is the ambition of all good whalemen. This cut represents the form of the spade. It is

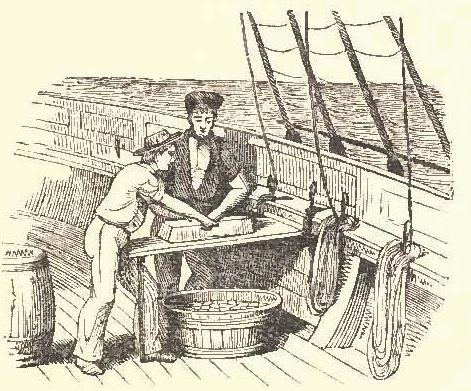

an instrument much used in the process of whaling. Each boat is provided with a spade, though it does not immediately come into requisition. It is employed to cut holes in the blubber after the capture of the whale, in which to fasten the tow-rope, or to plant the "whift," or small flag, by which the position of the dead whale may be ascertained, in case the boat puts off after others in the school. When the lines of two or more boats become entangled out of the reach of the hatchet, the spade is sometimes used to cut away. It is also convenient in case the sharks become troublesome. On board the ship it is made use of to cut the blubber from the carcass of the whale; and, in the hold blubber-room, spades (having short shafts). are the instruments employed to cut the large sheets of blubber called "blanket pieces" into blocks or "horse pieces" for the mincing knife. The boarding knife requires no explanation. The above cut gives a correct representation of it. In |

"cutting in" it is used to make holes in the blanket pieces for the blubber hook, and to cut them off when they have been drawn up to the blocks by the tackle attached to the windlass. Blubber knives are similar to the common knives