3 Oct, 2024 14:25

‘Colonization of the soul’: What made a European power fear this language?

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the colonial system started to collapse. Many countries in Asia and Africa gained independence in accordance with the principles of self-determination stated in the UN Charter of 1945 and a UN declaration adopted in 1960. However, decades of dependence on European powers and their policies had significantly altered the destinies of Afro-Asian peoples and disrupted historical processes that had existed prior to the colonial era.

This is particularly evident in Arab-African relations, which thrived throughout the Middle Ages. Arabic language, culture, and traditions had begun spreading on the African continent in the 7th century AD, shortly after the emergence of Islam.

France’s war against the Arabic language

In the 19th century, many European powers, including France, colonized Africa. From the outset, France waged a fierce campaign against Islamic culture and the Arabic language, striving to eliminate it from social and academic life and replace it with French. Colonial administrator Colonel Paul Marty, who served in Tunisia and Morocco and was an expert in the Arabic language, wrote about this in his book ‘Le Maroc de Demain’ (‘The Morocco of Tomorrow’), published in 1927.

“We must rigorously combat any attempt to provide education in Arabic, any intervention from Sharia scholars, and any manifestation of Islam. Only this way will we attract children, only through our own schools.”

French authorities even prohibited their compatriots in the occupied territories from communicating with the locals in any language other than French. This policy aligned with Paris’s broader educational and linguistic agenda. Following the fall of the Second French Empire in 1870, the Third Republic implemented free, compulsory, secular education under reforms carried out by French Prime Minister Jules Ferry (known as the Jules Ferry Laws). Expanding the use of the language throughout the territories was also French colonial policy.

Where is Arabic spoken in Africa?

Egypt was the first African country to adopt Arabic and then Islam, under the Shiite Fatimid dynasty between the 10th and 12th centuries. Through Egypt and the Red Sea, Arab Islamic influence then spread into Sudan and the Nile Valley.

Subsequent conquests, migration patterns, and trade developments facilitated the spread of Islam across a significant portion of the African continent, and this marked an important shift in cultural relations between Arabs and Africans. While Abyssinia (Ethiopia) remained steadfast in the Christian faith and sought to limit the activities of Arab missionaries, the remaining part of the eastern African coastline was more receptive to the spread of Arab-Islamic culture.

In places like Zanzibar, Kilwa (present-day Tanzania), and the Kenyan city of Mombasa, Arab trading hubs were established. Between the 12th and 15th centuries, Swahili culture flourished along the African coast; this was a result of close interaction with the Arabs. From the eastern shores of Africa, Arab-Islamic influences eventually reached the tropical lakes region which encompasses modern-day Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The Arabization and Islamization of the Maghreb (North Africa) also began during the wave of Arab conquests in the 7th and 8th centuries. In this region, Arabs partially integrated into the local Berber culture and spread the Arabic language and Islam to the western and central parts of the continent through four major trade routes. The first one linked Libya and Tunisia with the Lake Chad region, the second connected Tunisia with Hausa states, the third extended from Algeria to the middle course of the Niger River, and the fourth ran from Morocco to the river’s headwaters.

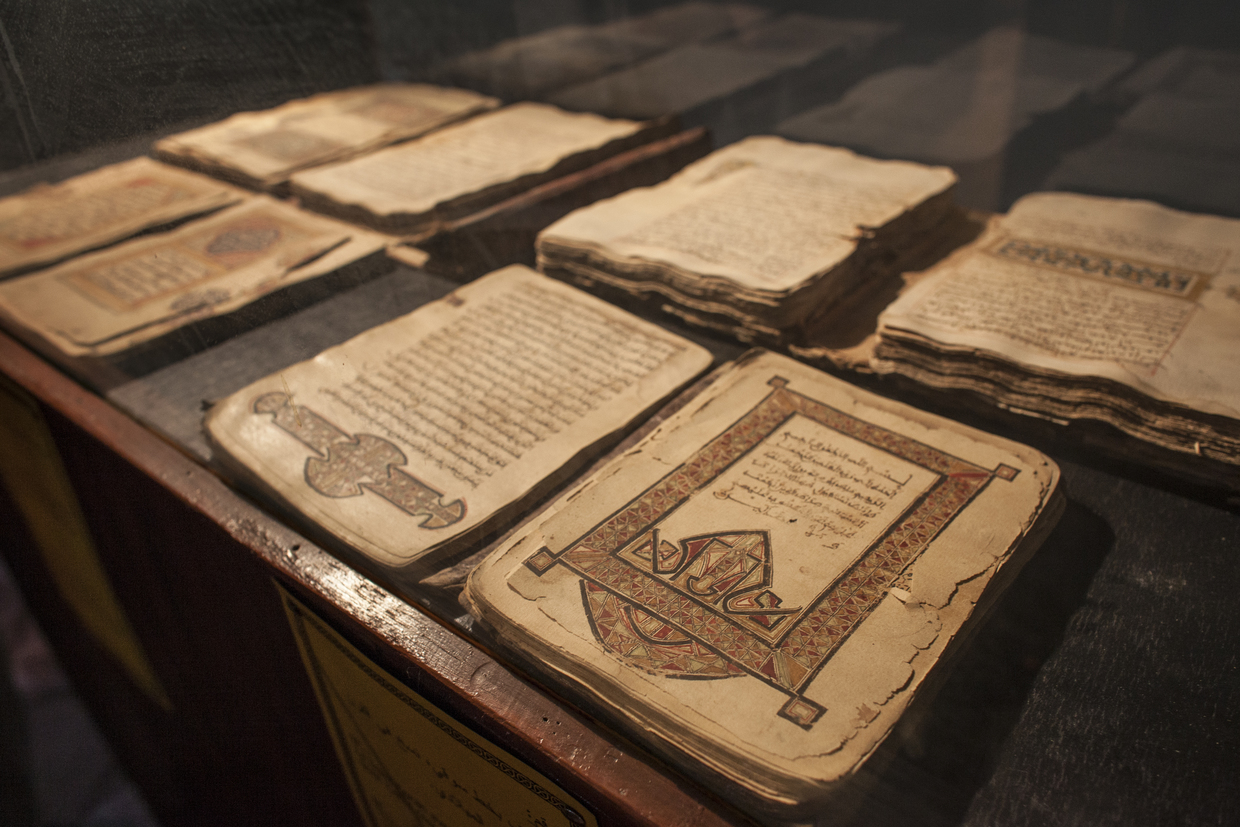

Over time, Arabic evolved from a language of religious worship to one of commerce, science, and culture, and eventually, the language of administration and law. Gradually, it became the official language of Arab countries along Africa’s northern coast. It was most widespread in the 15th-16th centuries during the era of the Songhai Empire (present-day Mali, Niger, and Nigeria).

For centuries, Arabic remained the dominant language in most Sahara-Sahel countries, and significantly influenced the languages and dialects of the indigenous populations. For instance, the languages of the Hausa, Fulani, and other peoples contain hundreds of words of Arabic origin, and Arabic script was also used for writing.

The spread of Arabic language and culture in Africa was quite different from the spread of the French language during the colonial period, since those were absolutely different historical eras. While colonialism encouraged domination over economically less developed nations in order to exploit their people and resources, medieval Arab conquests occurred in more culturally and economically advanced regions. Moreover, in the southern parts of Africa, Arabic language and culture spread in a natural way, being driven by active trade and the spread of Islam among the local population.

Francophonie as a tool for dominance

In 1970, France established the International Organization of Francophonie (Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, OIF), which brings together over 50 French-speaking countries around the world, including former colonies, along with seven associate members and 27 observer states. Notably, the primary criterion for joining the OIF is not the prevalence of the French language among the population but historical and cultural ties to France.

The term ‘Francophonie’ was coined by French geographer and writer Onésime Reclus (1837–1916) as a way to classify the world’s peoples. He was particularly interested in issues related to France and its colonies, especially Algeria, and believed that language was a factor that could unite diverse cultures. For instance, mainland France is strongly tied with countries in the Caribbean and Africa that were once under its control. Although the term became widespread only in the latter half of the 20th century, it reflects a concept in which language serves as a tool for cultural dominance.

Establishing complete control over Africa and exploiting its natural resources would have been impossible without the marginalization of Arabic and other major national languages. Critics of Francophonie argue that the French language, which European colonizers promoted as a gateway to culture and civilization, actually served the interests of colonialism and racism.

Algerian writer Latifa Ben Mansour, in her novel “Le Chant du Lys et du Basilic” (The Song of Lily and Basil) describes the introduction of French education on the African continent as an attempt to “colonize the soul.” The new educators systematically erased Arab history and literature from the collective memory of the people by instilling pride in France’s military victories and glorifying French poets and writers.

Linguistic dictatorship

Primary and higher education became a powerful tool that helped educate a generation that would loyally serve the interests of France. The students were taught to think and act like Frenchmen; then, the most suitable candidates were selected from among the graduates to hold important leadership posts in their countries.

Based on this policy, France began imposing the French language in its colonies, while at the same time marginalizing Arabic and other local languages. One of Paris’s most notorious methods was to instill the idea that other cultures and languages were inferior to French, and to foster hostility towards the Arabic language and Islam. France strived to remove Arabic from the scientific, intellectual, and political arena, rendering it unpopular and even shameful for the local elites.

Even today, French cultural and educational institutions in Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, and the Maghreb promote dialects at the expense of the classical Arabic language, which serves as a unifying factor in the Arab world.

Conversely, on its own territory, France fiercely fought to promote the official French language, disregarding all local dialects. According to the French Constitution, the only official language of the Fifth Republic is French, despite the historical existence of other indigenous languages such as Breton, Occitan, Lorraine Franconian, and others. To reinforce this status, the so-called Toubon Law was imposed in 1994, mandating the use of French in official government publications, advertisements, office communications, commercial contracts, all state-funded schools, and various other fields.

Cultural events organized by the OIF often promote the notion that Arabic is a dead language, similar to Latin. It is portrayed as complex and incomprehensible, unsuitable for communication or modern civilization, and as a language that can only be used for religious worship.

A new alphabet

One of the consequences of the colonial language policy was the replacement of the Arabic script with the Latin alphabet. The Arabic alphabet had been widely used in several African languages, including the Berber languages, Harari, Hausa, Fulani, Mandinka, Wolof, and Swahili. However, French and British colonizers systematically eradicated the Arabic script, and in the 1930s, books in major West and East African languages like Hausa and Swahili were first published using the Latin alphabet.

Starting in the 19th century, efforts emerged to standardize the use of the Latin alphabet for African languages. Notable examples include the Lepsius Standard Alphabet, developed in the mid-19th century for transcribing Egyptian hieroglyphs and later expanded for African languages, as well as the International African Alphabet, developed in the 1920s and 1930s by the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures.

In the 1960s and 1970s, UNESCO organized several “expert meetings” on this topic, including one in Bamako in 1966 and another in Niamey in 1978. At the latter meeting, the African Reference Alphabet was developed. Additionally, various national standardizations were proposed, such as the Pan-Nigerian Alphabet and the Berber Latin alphabet, specifically developed for the Northern Berber languages.

Arabic as an anti-colonial language

One of France’s most notorious strategies in its campaign against the Arabic language was the closure of Islamic educational institutions that taught the Quran and Sharia (religious law). The French sought to impose a classical European teaching system in Africa, and frequently sent educational missions to Paris, selecting the most distinguished people from the occupied territories to take part in them.

Efforts to Westernize traditional Islamic schools, the ‘madrasas’, and introduce the French language were met with staunch opposition from local Muslim communities, since the Sharia strictly forbids the use of any language other than Arabic during religious worship and Quranic recitation. In 1911, William Ponty, the Governor-General of French West Africa, issued a decree banning the use of Arabic in the Islamic courts in Dakar, Saint-Louis, and other cities. He also prohibited the publication of Islamic literature in order to suppress anti-colonial sentiments.

The fight against Arabic was also sealed in the legislature of African countries. In Algeria, following the start of the French occupation in 1830, activities like teaching Arabic, publishing books and newspapers, and even communicating in the language were forbidden. On March 8, 1938, then-Prime Minister of France Camille Chautemps issued a degree that banned the use of Arabic and classified it as a foreign language in Algeria. This law was one of the many decrees issued during the French occupation that significantly impacted Algerian society.

French postcolonialism

Today, French is the fifth most widely spoken language in the world, with 321 million speakers, 61.8% of whom reside in Africa. It is an official language in over 20 countries.

Apart from the OIF, France has many tools at its disposal for preserving its influence in Africa. These include television and radio programs as well as print media that focus exclusively on African issues while promoting French interests. For many years, citizens of the former French colonies could travel only using Air France or British Airways. Many Africans only discovered the existence of other countries when more airlines came to operate in Africa.

French companies control vital economic assets in the former colonies. In Côte d’Ivoire for instance, French companies control all essential services such as the water supply, electricity, telecommunications, transportation, ports, and major banks. The same holds true for trade, construction, and agriculture.

The currency used in West and Central Africa remains the CFA franc, which is printed in France and its purchasing power determined by Paris. Despite having a fixed exchange rate against the euro, the West African CFA franc cannot be used in Central Africa, and vice versa – the Central African CFA franc cannot be used in West Africa.

According to the agreement of the Financial Community of Africa (la Communauté Financière Africaine), the central banks of all African countries must keep at least 85% of their foreign exchange reserves in a so-called “trading account” at the French Central Bank, under the control of the French Ministry of Finance. However, the African nations cannot fully utilize these funds; Paris allows them access to just 15% of their reserves each year. If they require more, they have to borrow additional funds from the French Treasury.

Since 1961, France has kept the national reserves of 14 African countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon.

Rejection of the French language

In light of France’s weakening political influence, several African countries are abandoning the use of the French language. French is no longer the official language in Maghreb region countries like Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria, although it is still extremely widespread in the fields of education, trade, the economy, etc. Algeria is a particularly outspoken critic of the French language, especially since its relations with Paris have deteriorated in recent years.

In the Sahel region, following recent coups, many countries have distanced themselves from Paris in political, economic, trade, and military matters. In Mali, French ceased to be the official language in the summer of 2023, and became simply a language used for work. In contrast, Arabic and 12 other national languages were granted official status. On December 31, 2023, Burkina Faso’s Transitional National Assembly made a similar decision, amending the constitution and stripping French and English of their official status, and instead enshrining national languages as official languages.