Ancient Roman Homes

Domus

Much of what is known about the Roman Domus comes from excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum. While there are excavations of homes in the city of Rome, none of them retained the original integrity of the structures. The homes of Rome are mostly bare foundations, converted churches or other community buildings. The most famous of the Roman domus is the Domus of Livia and Augustus.

Little of the original architecture survives; only a single multi level section of the vast complex remains. Even in its original state, however, the House of Livia and Augustus is not a good representation of a typical domus, as the home belonged to one of Rome's most powerful, wealthy and influential citizens. In contrast, homes in Pompeii were preserved intact exactly as they were when they were occupied by Roman people 2000 years ago.

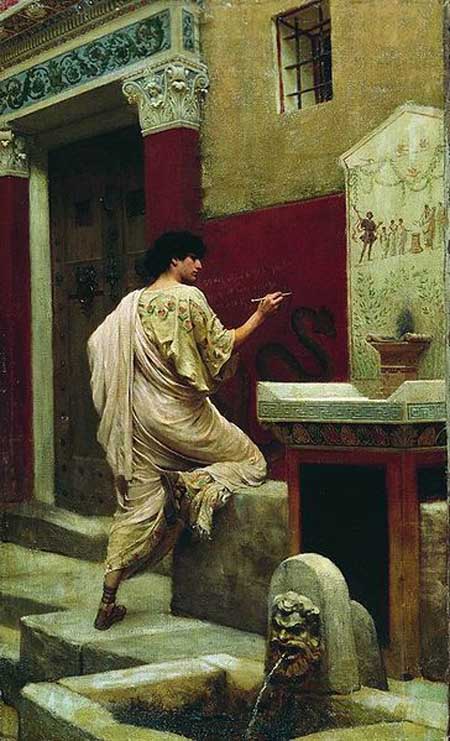

The rooms of the Pompeian domus were often painted in one of four styles: the first style imitated ashlar masonry, the second style represented public architecture, the third style focused on mystical creatures, and the fourth style combined the architecture and mythical creatures of the second and third styles.

The domus was occupied by the upper classes and some wealthy freedmen during the Republican and Imperial eras. It comes from the Ancient Greek word domi meaning structure since it was the standard type of housing in Ancient Greece. It could be found in almost all the major cities throughout the Roman territories. The modern English word domestic comes from Latin domesticus, which is derived from the word domus.

The word dom in modern Slavic languages means "home" and is a cognate of the Latin word, going back to Proto-Indo-European. Along with a domus in the city, many of the richest families of ancient Rome also owned a separate country house known as a villa. While many chose to live primarily, or even exclusively, in their villas, these homes were generally much grander in scale and on larger acres of land due to more space outside the walled and fortified city.

The elite classes of Roman society constructed their residences with elaborate marble decorations, inlaid marble paneling, door jambs and columns as well as expensive paintings and frescoes. Many poor and lower middle class Romans lived in crowded, dirty and mostly rundown rental apartments, known as insulae. These multi-level apartment blocks were built as high and tightly together as possible and held far less status and convenience than the private homes of the prosperous.

The homes of the early Etruscans, predecessors of the Romans, were simple, even for the wealthy or ruling classes. They were small familiar huts constructed on the axial plan of a central hall with an open skylight. It is believed that the Temple of Vesta was, in form, copied from the these early dwellings because the worship of Vesta began in individual homes. The huts were probably made of mud and wood with thatched roofs and a centre opening for the hearth's smoke to escape. This could have been the beginnings of the atrium, which was common in later homes. As Rome became more and more prosperous from trade and conquest, the homes of the wealthy increased in both size and luxury emulating both the Etruscan atrium house and Hellenistic peristyle house.

Interior

Atrium

The domus included multiple rooms, indoor courtyards, gardens and

beautifully painted walls that were elaborately laid out. The vestibulum

(entrance hall) led into a large central hall: the atrium, which was

the focal point of the domus and contained a statue of an altar to the

household gods. Leading off the Atrium were cubicula (bedrooms), a

dining room triclinium where guests could recline on couches and eat

dinner whilst reclining, a tablinum (living room or study) and tabernae

(shops on the outside, facing the street).

In cities throughout the Roman Empire, wealthy homeowners lived in buildings with few exterior windows. Glass windows weren't readily available: glass production was in its infancy. Thus a wealthy Roman citizen lived in a large house separated into two parts, and linked together through the tablinum or study or by a small passageway.

To protect the family from intruders, it would not face the streets, only its entrance providing more room for living spaces and gardens behind.

Surrounding the atrium were arranged the master's families' main rooms: the small cubicula or bedrooms, the tablinum or study, and the triclinium or dining-room. Roman homes were like Greek homes. Only two objects were present in the atrium of Caecilius in Pompeii: a small bronze box that stored precious family items and the lararium, a small shrine to the household gods, the Lares.

In the master bedroom was a small wooden bed and couch which usually consisted of some slight padding. As the domus developed, the tablinum took on a role similar to that of the study. In each of the other bedrooms there was usually just a bed. The triclinium had three couches surrounding a table. The triclinium often was similar in size to the master bedroom. The study was used as a passageway. If the master of the house was a banker or merchant the study often was larger because of the greater need for materials. Roman houses lay on an axis, so that a visitor was provided with a view through the fauces, atrium, and tablinum to the peristyle.

Interior Architectural Elements

Vestibulum (Fauces) The vestibulum was the main entryway hall of the

Roman Domus. It is usually only seen in grander structures, however many

urban homes had shops or rental space directly off the streets with the

front door between. The vestibulum would run the length of these front

Tabernae shops. This created security by keeping the main portion of the

domus off the street. In homes that did not have spaces for let in

front, either rooms or a closed area would still be separated by a

separate vestibulum.

Atrium (plural atria) The atrium was the most important part of the house, where guests and dependents (clients) were greeted. The atrium was open in the centre, surrounded at least in part by high-ceilinged porticoes that often contained only sparse furnishings to give the effect of a large space. In the centre was a square roof opening called the compluvium in which rainwater could come, draining inwards from the slanted tiled roof. Directly below the compluvium was the impluvium.

Impluvium An impluvium was basically a drain pool, a shallow rectangular sunken portion of the Atrium to gather rainwater, which drained into an underground cistern. The impluvium was often lined with marble, and around which usually was a floor of small mosaic.

Fauces These were similar in design and function of the vestibulum but were found deeper into the domus. Separated by the length of another room, entry to a different portion of the residence was accessed by these passage way we would call halls or hallways.

Tablinum Between the atrium and the peristyle, the tablinum would be constituted. Sort of office for the dominus, who would receive his clients for the morning salutatio. The dominus was able to command the house visually from this vantage point as the head of the social authority of the paterfamilias.

Triclinium The Roman dining room. The area had three couches, klinai, on three sides of a low square table.

Alae The open rooms on each side of the atrium. Their use is unknown.

Cubiculum Bedroom. The floor mosaics of the cubiculum often marked out a rectangle where the bed should be placed.

Culina The kitchen in a Roman house. It was dark and gloomy and smoke filled the room because there was no chimney. This is where slaves prepared food for their masters and guests in Roman times.

Posticum A servants' entrance also used by family members wanting to leave the house unobserved.

Exterior

The back part of the house was centred around the peristyle much as the

front centered on the atrium. The peristylium was a small garden often

surrounded by a columned passage, the model of the medieval cloister.

Surrounding the peristyle were the bathrooms, kitchen and summer

triclinium. The kitchen was usually a very small room with a small

masonry counter wood-burning stove. The wealthy had a slave who worked

as a cook and spent nearly all his or her time in the kitchen. During a

hot summer day the family ate their meals in the summer triclinium to

stave off the heat. Most of the light came from the compluvium and the

open peristylium.

There were no clearly defined separate spaces for slaves or for women. Slaves were ubiquitous in a Roman household and slept outside their masters' doors at night; women used the atrium and other spaces to work once the men had left for the forum. There was also no clear distinction between rooms meant solely for private use and public rooms, as any private room could be opened to guests at a moment's notice.

Insula

An insula dating from the early 2nd century A.D. in the Roman port town of Ostia Antica

In Roman architecture, an insula (Latin for "island," plural insulae) was a kind of apartment building that housed most of the urban citizen population of ancient Rome, including ordinary people of lower- or middle-class status (the plebs) and all but the wealthiest from the upper-middle class (the equites).

The traditional elite and the very wealthy lived in domus, large single-family residences, but the two kinds of housing were intermingled in the city and not segregated into separate neighborhoods. The ground-level floor of the insula was used for tabernae, shops and businesses, with the living space upstairs. Like modern apartment buildings, an insula might have a name, usually referring to the owner of the building.

Insulae, like domus, had running water and sanitation. But this kind of housing was sometimes constructed at minimal expense for speculative purposes, resulting in insulae of poor construction. They were built in timber, mud brick, and later primitive concrete, and were prone to fire and collapse, as described by Juvenal, whose satiric purpose in writing should be taken into account. Among his many business interests, Marcus Licinius Crassus speculated in real estate and owned numerous insulae in the city. When one collapsed from poor construction, Cicero purportedly stated that Crassus was happy that he could charge higher rents for a new building than the collapsed one.

Living quarters were typically smallest in the building's uppermost floors, with the largest and most expensive apartments being located on the bottom floors. The insulae could be up to six or seven stories high, and despite height restrictions in the Imperial era, a few reached eight or nine stories. The notably large Insula Felicles or Felicula was located near the Flaminian Circus in Regio IX; the early Christian writer Tertullian condemns the hubris of multiple-story buildings by comparing the Felicles to the towering homes of the gods. A single insula could accommodate over 40 people in only 3,600 sq ft; however, the entire structure usually had about 6 to 7 apartments, each had about 1000 sq ft.

Because of safety issues and extra flights of stairs, the uppermost floors were the least desirable, and thus the cheapest to rent. Often those floors were without heating, running water or lavatories, which meant their occupants had to use Rome's extensive system of public restrooms (latrinae). Despite prohibitions, residents would sometimes dump trash and human excrement out the windows and into the surrounding streets and alleys.

The lower class Romans - plebeians - lived in apartment houses, called flats, above or behind their shops. Even fairly well-to-do tradesmen might chose to live in an apartment-building compound over their store, with maybe renters on the upper stories. Their own apartments might be quite roomy, sanitary and pleasant, occasionally with running water. But others were not that nice.

In the apartment houses an entire family (grandparents, parents, children) might all be crowded into one room, without running water. They had to haul their water in from public facilities. Fire was a very real threat because people were cooking meals in crowded quarters, and many of the flats were made of wood. They did not have toilets. They had to use public latrines (toilets).

Villa

A Roman villa was living space during the Roman Republic and the Roman

Empire. A villa was originally a Roman country house built for the upper

class. According to Pliny the Elder, there were two kinds of villas:

the villa urbana, which was a country seat that could easily be reached

from Rome (or another city) for a night or two, and the Villa rustica,

the farm-house estate permanently occupied by the servants who had

charge generally of the estate. The villa rustica centered on the villa

itself, perhaps only seasonally occupied.

Under the Empire there was a concentration of Imperial villas near the Bay of Naples, especially on the Isle of Capri, at Monte Circeo on the coast and at Antium (Anzio). Wealthy Romans escaped the summer heat in the hills round Rome, especially around Frascati (cf. Hadrian's Villa). Cicero is said to have possessed no less than seven villas, the oldest of which was near Arpinum, which he inherited. Pliny the Younger had three or four, of which the example near Laurentium is the best known from his descriptions.

The late Roman Republic witnessed an explosion of villa construction in Italy, especially in the years following the dictatorship of Sulla. In Etruria, the villa at Settefinestre has been interpreted as being one of the latifundia, or large slave-run villas, that were involved in large-scale agricultural production. At Settefinestre and elsewhere, the central housing of such villas was not richly appointed. Other villas in the hinterland of Rome are interpreted in light of the agrarian treatises written by the elder Cato, Columella and Varro, both of whom sought to define the suitable lifestyle of conservative Romans, at least in idealistic terms.

The Empire contained many kinds of villas, not all of them lavishly appointed with mosaic floors and frescoes. Some were pleasure houses such as those - like Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli - that were sited in the cool hills within easy reach of Rome or - like the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum - on picturesque sites overlooking the Bay of Naples.

Some villas were more like the country houses of England or Poland, the visible seat of power of a local magnate, such as the famous palace rediscovered at Fishbourne in Sussex. Suburban villas on the edge of cities were also known, such as the Middle and Late Republican villas that encroached on the Campus Martius, at that time on the edge of Rome, and which can be also seen outside the city walls of Pompeii.

These early suburban villas, such as the one at Rome's Auditorium site or at Grottarossa in Rome, demonstrate the antiquity and heritage of the villa suburbana in Central Italy. It is possible that these early, suburban villas were also in fact the seats of power (maybe even palaces) of regional strongmen or heads of important families (gentes). A third type of villa provided the organizational center of the large holdings called latifundia, that produced and exported agricultural produce; such villas might be lacking in luxuries.

By the 4th century, villa could simply connote an agricultural holding: Jerome translated the Gospel of Mark (xiv, 32) chorion, describing the olive grove of Gethsemane, with villa, without an inference that there were any dwellings there at all (Catholic Encyclopedia "Gethsemane").

Some sumptuous Roman villas featured complex floor mosaics

Architecture

By the first century BC, the "classic" villa took many architectural

forms, with many examples employing atrium or peristyle, for enclosed

spaces open to light and air. A villa might be quite palatial, such as

the imperial villas built on seaside slopes overlooking the Bay of

Naples at Baiae; others were preserved at Stabiae and Herculaneum by the

ashfall and mudslide from the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, which also

preserved the Villa of the Papyri and its libraries.

Deeper in the countryside, even non-commercial villas were largely self-supporting with associated farms, olive groves, and vineyards. Roman writers refer with satisfaction to the self-sufficiency of their villas, where they drank their own wine and pressed their own oil, a commonly used literary topos. An ideal Roman citizen was the independent farmer tilling his own land, and the agricultural writers wanted to give their readers a chance to link themselves with their ancestors through this image of self-sufficient villas. The truth was not too far from it, either, while even the profit-oriented latifundia probably grew enough of all the basic foodstuffs to provide for their own consumption.

Large villas dominated the rural economy of the Po valley, Campania, and Sicily, and were also found in Gaul. Villas were centers of a variety of economic activity such as mining, pottery factories, or horse raising such as those found in northwestern Gaul. Villas specializing in the sea-going export of olive oil to Roman legions in Germany were a feature of the southern Iberian province of Hispania Baetica. Some luxurious villas have been excavated in North Africa in the provinces of Africa and Numidia, or at Fishbourne in Britannia.

Certain areas within easy reach of Rome offered cool lodgings in the heat of summer. Maecenas asked what kind of house could possibly be suitable at all seasons. The emperor Hadrian had a villa at Tibur (Tivoli), in an area that was popular with Romans of rank. Hadrian's Villa (123 AD) was more like a palace, as Nero's palace, his Domus Aurea on the Palatine Hill in Rome, was disposed in groupings in a planned rustic landscape, more like a villa.

Cicero had several villas. Pliny the Younger described his villas in his letters. The Romans invented the seaside villa: a vignette in a frescoed wall at the house of Lucretius Fronto in Pompeii still shows a row of seafront pleasure houses, all with porticos along the front, some rising up in porticoed tiers to an altana at the top that would catch a breeze on the most stifling evenings (Veyne 1987 ill. p 152)

Late Roman owners of villae had luxuries like hypocaust-heated rooms with mosaic floors. As the Roman Empire collapsed in the fourth and fifth centuries, the rustic villas were more and more isolated and came to be protected by walls. Though in England the villas were abandoned, looted, and burned by Anglo-Saxon invaders in the fifth century, in other areas large working villas were donated by aristocrats and territorial magnates to individual monks, often to become the nucleus of famous monasteries. In this way, the villa system of late Antiquity was preserved into the Early Middle Ages.

Saint Benedict established his influential monastery of Monte Cassino in the ruins of a villa at Subiaco that had belonged to Nero; Around 590, Saint Eligius was born in a highly-placed Gallo-Roman family at the 'villa' of Chaptelat near Limoges, in Aquitaine. The abbey at Stavelot was founded ca 650 on the domain of a former villa near Liege and the abbey of Vezelay had a similar founding. As late as 698, Willibrord established an abbey at a Roman villa of Echternach, in Luxembourg near Trier, which was presented to him by Irmina, daughter of Dagobert II, king of the Franks.