Siege of Baghdad (1258)

| Siege of Baghdad (1258) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasions and conquests | |||||||

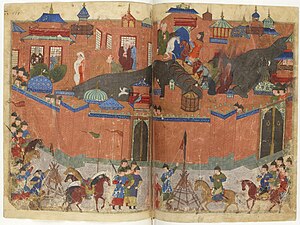

Hulagu's army besieging the walls of Baghdad | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 100,000–150,000[6][7][8] | 50,000[citation needed] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown but believed to be minimal | |||||||

The siege of Baghdad was a siege that took place in Baghdad in 1258, lasting for 13 days from January 29, 1258, until February 10, 1258. The siege, laid by Ilkhanate Mongol forces and allied troops, involved the investment, capture, and sack of Baghdad, which was the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate at that time. Most of the residents were massacred--perhaps hundreds of thousands. The Mongols were under the command of Hulagu Khan, brother of the khagan Möngke Khan, who had intended to further extend his rule into Mesopotamia but not to directly overthrow the Caliphate. Möngke, however, had instructed Hulagu to attack Baghdad if the Caliph Al-Musta'sim refused Mongol demands for his continued submission to the khagan and the payment of tribute in the form of military support for Mongol forces in Persia.

Hulagu began his campaign in Persia against the strongholds of Nizari Ismailis, who lost their stronghold of Alamut. He then marched on Baghdad, demanding that Al-Musta'sim accede to the terms imposed by Möngke on the Abbasids. Although the Abbasids had failed to prepare for the invasion, the Caliph believed that Baghdad could not fall to invading forces and refused to surrender. Hulagu subsequently besieged the city, which surrendered after 12 days.

During the next week, the Mongols sacked Baghdad, committing numerous atrocities. Historians are uncertain about the level of destruction of library books and the Abbasids' vast libraries. The Mongols executed Al-Musta'sim and massacred many residents of the city, which was left greatly depopulated. The siege marked the end of the Islamic Golden Age, during which the caliphs had extended their rule from the Iberian Peninsula to Sindh, and which was also marked by many cultural achievements in diverse fields.[11]

Background[edit source]

Baghdad had for centuries been the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, the third of the caliphates, whose rulers were descendants of Abbas, an uncle of Muhammad. In 751, the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads and moved the Caliph's seat from Damascus to Baghdad. At the city's peak, it was populated by approximately one million people and was defended by an army of 60,000 soldiers. By the middle of the 13th century the power of the Abbasids had declined and Turkic and Mamluk warlords often held power over the Caliphs.[12]

Baghdad still retained much symbolic significance, and it remained a rich and cultured city. The Caliphs of the 12th and 13th centuries had begun to develop links with the expanding Mongol Empire in the east. Caliph an-Nasir li-dini'llah, who reigned from 1180–1225, may have attempted an alliance with Genghis Khan when Muhammad II of Khwarezm threatened to attack the Abbasids.[12] It's possible that some Crusader captives were sent as tribute to the Mongol khagan.[13]

According to The Secret History of the Mongols, Genghis and his successor, Ögedei Khan, ordered their general Chormaqan to attack Baghdad.[14] In 1236, Chormaqan led a division of the Mongol army to Irbil,[15] which remained under Abbasid rule. Further raids on Irbil and other regions of the caliphate became nearly annual occurrences.[16] Some raids were alleged to have reached Baghdad itself,[17] but these Mongol incursions were not always successful, with Abbasid forces defeating the invaders in 1238[18] and 1245.[19]

Despite their successes, the Abbasids hoped to come to terms with the Mongols and by 1241 had adopted the practice of sending an annual tribute to the court of the khagan.[17] Envoys from the caliph were present at the coronation of Güyük Khan as khagan in 1246[20] and that of Möngke Khan in 1251.[21] During his brief reign, Güyük insisted that Caliph Al-Musta'sim fully submit to Mongol rule and come personally to Karakorum. The khagans blamed Baiju for the caliph's refusal and other resistance by the Abbasids to increased attempts by the Mongols to extend their power.

Hulagu's expedition[edit source]

Planning[edit source]

In 1257, Möngke resolved to establish firm authority over Mesopotamia, Syria, and Persia. The khagan gave his brother, Hulagu, authority over a subordinate khanate and army, the Ilkhanate, and instructions to compel the submission of various Muslim states, including the caliphate. Though not seeking the overthrow of Al-Musta'sim, Möngke ordered Hulagu to destroy Baghdad if the Caliph refused his demands of personal submission to Hulagu and the payment of tribute in the form of a military detachment, which would reinforce Hulagu's army during its campaigns against Persian Ismaili states.

In preparation for his invasion, Hulagu raised a large expeditionary force, conscripting one out of every ten military-age males in the entirety of the Mongol Empire, assembling what may have been the most numerous Mongol army to have existed and, by one estimate, 150,000 strong.[22] Generals of the army included the Oirat administrator Arghun Agha, Baiju, Buqa Temür, Guo Kan, and Kitbuqa, as well as Hulagu's brother Sunitai and various other warlords.[23] The force was also supplemented by Christian forces, including the King of Armenia and his army, a Frankish contingent from the Principality of Antioch,[2] and a Georgian force, seeking revenge on the Muslim Abbasids for the sacking of their capital, Tiflis, decades earlier by the Khwarazm-Shahs.[1] About 1,000 Chinese artillery experts accompanied the army,[24] as did Persian and Turkic auxiliaries, according to Ata-Malik Juvayni, a contemporary Persian observer.

Early campaigns[edit source]

Hulagu led his army first to Persia, where he successfully campaigned against the Lurs, the Bukhara, and the remnants of the Khwarezm-Shah dynasty. After subduing them, Hulagu directed his attention toward the Nizari Ismailis and their Grand Master, Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad, who had attempted the murder of both Möngke and Hulagu's friend and subordinate, Kitbuqa. Though the Order of Assassins failed in both attempts, Hulagu marched his army to their stronghold of Alamut, which he captured. The Mongols later executed the Assassins' Grand Master, Imam Rukn al-Din Khurshah, who had briefly succeeded 'Ala al-Din Muhammad from 1255–1256.

Capture of Baghdad[edit source]

Hulagu's march to Baghdad[edit source]

After defeating the Assassins, Hulagu sent word to Al-Musta'sim, demanding his acquiescence to the terms imposed by Möngke. Al-Musta'sim refused, in large part due to the influence of his advisor and grand vizier, Ibn al-Alkami. Historians have ascribed various motives to al-Alkami's opposition to submission, including treachery[25] and incompetence.[26] Either way, it appears that he misled the Caliph about the severity of the invasion and assured Al-Musta'sim that, if the capital of the caliphate were to be endangered by a Mongol army, the Islamic world would rush to its aid.[26]

Although he replied to Hulagu's demands in a manner that the Mongol commander found menacing and offensive enough to break off negotiations,[27] Al-Musta'sim neglected to summon armies to reinforce the troops at his disposal in Baghdad. Nor did he strengthen the city's walls. By January 11 the Mongols were close to the city,[26] establishing themselves on both banks of the Tigris River so as to form a pincer around the city. Al-Musta'sim finally decided to do battle with them and sent out a force of 20,000 cavalry to attack the Mongols. The cavalry were decisively defeated by the Mongols, whose sappers breached dikes along the Tigris River and flooded the ground behind the Abbasid forces, trapping them.[26]

Siege of the city[edit source]

The Abbasid caliphate supposedly called upon 50,000 soldiers for the defense of their capital, including the 20,000 cavalry under al-Musta'sim. However, these troops were assembled hastily, making them poorly equipped and disciplined. Although the caliph technically had the authority to summon soldiers from other Muslim empires to defend his realm, he neglected or lacked the ability to do so. His taunting opposition had lost him the loyalty of the Mamluks, and the Syrian emirs, whom he supported, were busy preparing their own defenses.[28]

On January 29, the Mongol army began its siege of Baghdad, constructing a palisade and a ditch around the city. Employing siege engines and catapults, the Mongols attempted to breach the city's walls, and, by February 5, had seized a significant portion of the defenses. Realizing that his forces had little chance of retaking the walls, Al-Musta'sim attempted to open negotiations with Hulagu, who rebuffed the Caliph. Around 3,000 of Baghdad's notables also tried to negotiate with Hulagu but were murdered.[29] Five days later, on February 10, the city surrendered, but the Mongols did not enter the city until the 13th, beginning a week of massacre and destruction.[citation needed]

Destruction[edit source]

Many historical accounts detailed the cruelties of the Mongol conquerors. Baghdad was a depopulated, ruined city[30][31] for several decades and only gradually recovered some of its former glory.[32]

Contemporary accounts state Mongol soldiers looted and then destroyed mosques, palaces, libraries, and hospitals. Priceless books from Baghdad's thirty-six public libraries were torn apart, the looters using their leather covers as sandals.[33] Grand buildings that had been the work of generations were burned to the ground. The House of Wisdom (the Grand Library of Baghdad), containing countless precious historical documents and books on subjects ranging from medicine to astronomy, was destroyed. Claims have been made that the Tigris ran red from the blood of the scientists and philosophers killed.[34][35] Images of violence toward books appear in the 14th century; the tale of the destruction of books – tossed into the Tigris such that the water turned black from the ink – seems to originate from the 16th century.[36][37] Michal Biran argues that this story was likely a literary trope to demonstrate Mongol barbarity.[38]

Citizens attempted to flee, but were intercepted by Mongol soldiers who killed in abundance, sparing no one, not even children. Martin Sicker writes that close to 90,000 people may have died.[39][40] The Mongols in 1262 boasted to king Louis IX of France that they had killed two million in Baghdad, certainly an exaggeration.[41]

The caliph Al-Musta'sim was captured and forced to watch as his citizens were murdered and his treasury plundered. According to most accounts, the caliph was killed by trampling. The Mongols rolled the caliph up in a rug, and rode their horses over him, as they believed that the earth would be offended if it were touched by royal blood.

Hulagu had to move his camp upwind of the city, due to the stench of decay from the ruined city.[42]

The historian David Morgan has quoted Wassaf (who himself was born in 1265, seven years after the razing of the city) describing the destruction: "They swept through the city like hungry falcons attacking a flight of doves, or like raging wolves attacking sheep, with loose reins and shameless faces, murdering and spreading terror...beds and cushions made of gold and encrusted with jewels were cut to pieces with knives and torn to shreds. Those hiding behind the veils of the great Harem were dragged...through the streets and alleys, each of them becoming a plaything...as the population died at the hands of the invaders."[43]

Some modern historians have cast doubt on the vehemently anti-Mongol medieval sources.[44] George Lane (SOAS), for example, doubts the Grand Library was destroyed, as the learned members of the Mongol command such as Nasir al-Din Tusi would not have allowed it, and that disease was the major cause of death.[45] Primary sources state that Tusi saved thousands of volumes and installed them into a building in Marāgheh.[46][47][48]

Causes for agricultural decline[edit source]

Some historians[who?] believe that the Mongol invasion destroyed much of the irrigation infrastructure that had sustained Mesopotamia for many millennia.[citation needed] Canals were cut as a military tactic and never repaired. So many people died or fled that neither the labour nor the organization were sufficient to maintain the canal system. It broke down or silted up. This theory was advanced (not for the first time) by historian Svatopluk Souček in his 2000 book, A History of Inner Asia.

Other historians point to soil salination as the primary cause for the decline in agriculture.[49]

Aftermath[edit source]

Hulagu left 3,000 Mongol soldiers behind to rebuild Baghdad. Ata-Malik Juvayni was later appointed governor of Baghdad, Lower Mesopotamia, and Khuzistan after Guo Kan went back to the Yuan dynasty to assist Kublai's conquest over the Song dynasty. Hulagu's Eastern Christian wife, Dokuz Khatun, successfully interceded to spare the lives of Baghdad's Christian inhabitants.[50] Hulagu offered the royal palace to the Nestorian Catholicos Mar Makikha, and ordered a cathedral to be built for him.[51]

Initially, the fall of Baghdad came as a shock to the whole Muslim world. But after many years of utter devastation, the city gradually became an economic center where international trade, the minting of coins and religious affairs flourished under the succeeding Ilkhanate.[52] The chief Mongol darughachi was thereafter stationed in the city.[53]

Berke, a grandson of Genghis Khan who had converted to Islam in 1252, became enraged that Hulagu destroyed Baghdad. Muslim historian Rashid al-Din Hamadani quoted Berke Khan as sending the following message to Möngke Khan, protesting the attack on Baghdad, (not knowing Möngke had died in China): "He (Hulagu) has sacked all the cities of the Muslims. With the help of God I will call him to account for so much innocent blood."

Although hesitant at first to go to war with Hulagu out of Mongol brotherhood, the economic situation of the Golden Horde led him to declare war against the Ilkhanate. This became known as the Berke–Hulagu war.[54]

See also[edit source]

- Siege of Baghdad (1157)

- Abbasid architecture

- History of Baghdad

- Islamic Golden Age

- Soil salination

- Tigris–Euphrates river system

- Mamluk Sultanate

References[edit source]

Citations[edit source]

- ^ a b Khanbaghi, 60

- ^ a b c Demurger, 80–81; Demurger 284

- ^ John Masson Smith, Jr. Mongol Manpower and Persian Population, p. 276

- ^ Din, Rashid Al. Jami' al-tawarikh [Compendium of Chronicles]. p. 41.

- ^ John Masson Smith, Jr. Mongol Manpower and Persian Population. pp. 271–99

- ^ a b c L. Venegoni (2003). Hülägü's Campaign in the West (1256–1260) Archived 2012-02-11 at the Wayback Machine, Transoxiana Webfestschrift Series I, Webfestschrift Marshak 2003.

- ^ National Geographic, v. 191 (1997)

- ^ "The Sack Of Baghdad In 1258 – One Of The Bloodiest Days In Human History". 15 February 2019.

- ^ Andre Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Vol.2, (Brill, 2002), 13.

- ^ The different aspects of Islamic culture: Science and technology in Islam, Vol. 4, Ed. A. Y. Al-Hassan, (Dergham sarl, 2001), 655.

- ^ Justin Marozzi, Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood--A History in Thirteen Centuries (2014) ch 4, 5.

- ^ a b Jack Weatherford Genghis Khan and the making of the modern world, p. 135

- ^ Jack Weatherford Genghis Khan and the making of the modern world, p. 136

- ^ Sh.Gaadamba Mongoliin nuuts tovchoo (1990), p. 233

- ^ Timothy May Chormaqan Noyan, p. 62

- ^ Al-Sa'idi,., op. cit., pp. 83, 84, from Ibn al-Fuwati

- ^ a b C. P. Atwood Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p. 2

- ^ Spuler, op. cit., from Ibn al-'Athir, vol. 12, p. 272.

- ^ "Mongol Plans for Expansion and Sack of Baghdad". alhassanain.com. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26.

- ^ Giovanni, da Pian del Carpine (translated by Erik Hildinger) The story of the Mongols whom we call the Tartars (1996), p. 108

- ^ "Wednesday University Lecture 3". depts.washington.edu. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "European & Asian History". telusplanet.net. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ^ Rashiddudin, Histoire des Mongols de la Perse, E. Quatrieme ed. and trans. (Paris, 1836), p. 352.

- ^ L. Carrington Goodrich (2002). A Short History of the Chinese People (illustrated ed.). Courier Dover Publications. p. 173. ISBN 0-486-42488-X. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

In the campaigns waged in western Asia (1253–1258) by Jenghis' grandson Hulagu, "a thousand engineers from China had to get themselves ready to serve the catapults, and to be able to cast inflammable substances." One of Hulagu's principal generals in his successful attack against the caliphate of Baghdad was Chinese.

- ^ Zaydān, Jirjī (1907). History of Islamic Civilization, Vol. 4. Hertford: Stephen Austin and Sons, Ltd. p. 292. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d Davis, Paul K. (2001). Besieged: 100 Great Sieges from Jericho to Sarajevo. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 67.

- ^ Nicolle

- ^ James Chambers, "The Devil's Horsemen," p. 144.

- ^ Fattah, Hala. A Brief History of Iraq. Checkmark Books. p. 101.

- ^ James Chambers, The Devil's Horsemen, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, ç1979, p.145

- ^ Guy Le Strange, Baghdad During the Abbasid Caliphate, Clarendon Press, Oxford, ç1901, p.344

- ^ Timothy Ward, The Mongol Conquests in World History, Reakton Books, London, ç2012, p.126

- ^ Murray, S.A.P. (2012). The library: An illustrated history. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, pp. 54.

- ^ Frazier, I., "Invaders: Destroying Baghdad," New Yorker Magazine, [Special edition: Annals of History], April 25, 2005, Online Issue Archived 2018-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Szczepanski, Kallie. "How the Mongols Took Over Baghdad in 1258." ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/the-mongol-siege-of-baghdad-1258-195801 (accessed February 10, 2021).

- ^ James Raven, Introduction: The Resonances of Loss, in Lost Libraries: The Destruction of Great Book Collections since Antiquity, ed. James Raven (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), p. 11.

- ^ Ibn Khaldūn, Tārīkh Ibn Khaldūn, ed. Khalīl Shaḥḥadāh (Beirut: Dār al-Fikr, 2000), p. 5:613.

- ^ Biran, Michal (18 March 2019). "Libraries, Books, and Transmission of Knowledge in Ilkhanid Baghdad". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 62 (2–3): 464–502. doi:10.1163/15685209-12341485. S2CID 167078796 – via Brill.

- ^ (Sicker 2000, p. 111)

- ^ Rene Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, ç1970 p.356

- ^ Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the Islamic World-from Conquest to Conversion, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2017, pp. 171, 172.

- ^ Henry Howorth, History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century, Part I, Burt Franklin, New York, ç1876, p. 127

- ^ Marozzi, Justin (29 May 2014). Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood. Penguin Books. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0-14-194804-1.

- ^ Michal Biran, The Mongols’ Middle East, ed. De Nicola & Melville, Brill, Boston, 2016 pp. 140–141

- ^ George Lane (Society of Ancient Sources), Iran After the Mongols: The Idea of Iran, Vol.8, ed. S. Babaie, I.B. Tauris, London, ç2019, pp. 17–18

- ^ Ibn Taymiyyah, Majmū’ al-Fatāwa (Dār al-Wafā’, 2005), p. 13:111.

- ^ Khạlīl b. Aybak al-̣Safadī, Kitāb al-Wāfī bi’l-Wafayāt (Beirut: Dār Ihyā’ al-Turāth al-Islāmī, 2000), p. 1:147, #114.

- ^ Abdulhadi Hairi, "Nasir al-Din Tusi-His Supposed Political Role in the Mongol Invasion of Baghdad", Islamic Studies-Univ. of Montreal, ç1968

- ^ "Saudi Aramco World : The Greening of the Arab East: The Planters". saudiaramcoworld.com. Archived from the original on 2006-01-25. Retrieved 2006-02-03.

- ^ Maalouf, 243

- ^ Foltz, 123

- ^ Coke, Richard (1927). Baghdad, the City of Peace. London: T. Butterworth. p. 169.

- ^ Kolbas, Judith G. (2006). The Mongols in Iran: Chingiz Khan to Uljaytu, 1220–1309. London: Routledge. p. 156. ISBN 0-7007-0667-4.

- ^ Johan Elverskog (6 June 2011). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 186–. ISBN 978-0-8122-0531-2.

Sources and further reading[edit source]

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven. 1998. Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281 (first edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46226-6.

- Demurger, Alain. 2005. Les Templiers. Une chevalerie chrétienne au Moyen Âge. Éditions du Seuil.

- ibid. 2006. Croisades et Croisés au Moyen-Age. Paris: Groupe Flammarion.

- Falagas, Matthew E., Effie A. Zarkadoulia, and George Samonis. "Arab science in the golden age (750–1258 CE) and today." The FASEB Journal 20.10 (2006): 1581-1586. online

- Fancy, Nahyan, and Monica H. Green. "Plague and the Fall of Baghdad (1258)." Medical history 65.2 (2021): 157-177. online

- Hassan, Mona F. "Loss of caliphate: The trauma and aftermath of 1258 and 1924" (PhD dissertation, Princeton University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2009. 341296).

- Howorth, Henry. History of the Mongols (1888) 3:113 to 133. online

- Khanbaghi, Aptin. 2006. The fire, the star, and the cross: minority religions in medieval and early modern Iran. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Marozzi, Justin. Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood--A History in Thirteen Centuries (2014) ch 5. excerpt

- Morgan, David. 1990. The Mongols. Boston: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17563-6.

- Neggaz, Nassima. "The falls of Baghdad in 1258 and 2003: A study in Sunnī-Shī'ī clashing memories" (PhD dissertation, Georgetown University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2013. 3606870).

- Nicolle, David, and Richard Hook (illustrator). 1998. The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-407-9.

- Saunders, J.J. 2001. The History of the Mongol Conquests. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1766-7.

- Sicker, Martin. 2000. The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96892-8.

- Souček, Svat. 2000. A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-65704-0.

- Wu. Pai-nan Rashid. "The Fall of Baghdad and the Mongol Rule in Al-Iraq, 1258-1335' (PhD dissertation, U of Utah, 1974)

Primary sources[edit source]

- Gilli-Elewy, Hend. "Al-awādi al-ğāmia: A Contemporary Account of the Mongol Conquest of Baghdad, 656/1258." Arabica 58.5 (2011): 353-371.

External links[edit source]

- article describing Hulagu's conquest of Baghdad, written by Ian Frazier, appeared in the April 25, 2005 issue of The New Yorker.

- 1258 in the Mongol Empire

- Baghdad under the Abbasid Caliphate

- Battles involving the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia

- Battles involving the Kingdom of Georgia

- Sieges involving the Mongol Empire

- Conflicts in 1258

- Invasions by the Mongol Empire

- 13th-century massacres

- Sieges involving the Abbasid Caliphate

- Sieges of Baghdad

- 13th century in the Kingdom of Georgia

- 13th century in the Abbasid Caliphate

- Battles involving the Principality of Antioch

- Hulagu Khan

- Book burnings

- Battles involving the Ilkhanate

- Looting

- Razed cities

- Massacres of Muslims