Commercial Whaling in Newfoundland and Labrador to 1900

Less than 40 years after Cabot's discovery of North America, seasonal whaling stations were established on the Labrador side of the Strait of Belle Isle. The coastal waters of Newfoundland and Labrador are among the best suited places in the world for cetacea, the family to which whales belong. Of the approximately 80 species of cetacea, which also includes dolphins and porpoises, about 20 can be found in the North-west Atlantic.

Whales hunted in Newfoundland and Labrador prior to 1972 include the blue, fin, southern and Greenland right whales, humpback and minke, also known locally as "herring hog" and "grampus". These are baleen whales which feed by filtering small prey through modified plates which have hair-like fringes called "whalebone" and "baleen". Pilot whales or "potheads", the most common inshore species in Newfoundland and the only toothed whale hunted commercially, were killed by driving pods (herds) ashore.

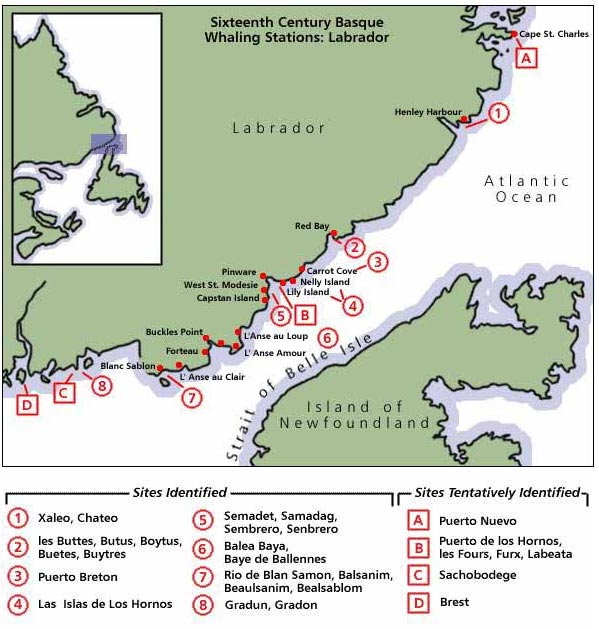

Commercial whaling began in North America during the second quarter of the 16th century, when the Basques began to hunt Greenland and black right whales from at least a dozen harbours along the Labrador coast in strategic proximity to migration routes.

Using small open boats and hand thrown harpoons, the industry expanded significantly during the 1560s and 1570s, when more than 20 ships participated annually. The subsequent decline of the industry was influenced by the reduction of stocks by possible over-hunting and migration changes, the development of a more lucrative whale fishery at Spitsbergen, growing competition from Dutch and English whalers, and domestic strife in Spain.

By the early 1580s, the overseas Basque whale fishery had virtually ended, although records exist of individual voyages being fitted out simultaneously to prosecute the Labrador whale and cod fisheries as late as the summer of 1632.

Although the growing 18th and early 19th century resident population of Newfoundland depended primarily upon the cod and seal fisheries, whale carcasses washed ashore or chanced upon at sea were rich prizes for their oil, baleen and meat. On 8 July 1768, for example, a whale towed into Trinity by Thomas Keen "made 11 tons of oil" (Lester Diaries), and in 1897 James and John Rourke of Mall Bay sold a carcass to M. Tobin of St. Mary's who then had it rendered into oil. The whale had been found "dead between Crapaud Point and [Cape] St. Mary's Bank" (Evening Herald: 9 July 1897).

There is additional evidence that some of the larger 19th century merchant houses were also active in small-scale commercial whaling. A whaling company, for example, was established at Gaultois by Newman and Company. At the height of this operation in the late 1870s, 40 to 50 whales were captured annually. It is therefore clear that some Newfoundlanders were engaged in small-scale seasonal inshore whaling during the late 19th century. Their limited whaling activity, in turn, was fostered by two Scottish sealing and whaling companies involved in the Newfoundland seal fishery between 1874 and 1900. They sometimes used Newfoundlanders on whaling voyages to the Davis Strait and Baffin Bay hunting grounds, and their St. John's factories often processed those occasional carcasses obtained by indigenous "whalers".

These relatively small-scale traditional whaling operations were superseded and dramatically enhanced following the results of experiments in Norway. Svend Foyn, a Norwegian sealing master, introduced fast steam-powered catchers fitted with grenade-firing harpoon guns, a new hunting technology which allowed for the exploitation of heretofore ignored fast-swimming species such as blue and fin whales.

Subsequent over-hunting off Norway caused whaling entrepreneurs to look elsewhere for unexploited stocks. As a result they constructed whaling stations in Iceland in 1883, and in the Faeroes in 1894, before turning to Newfoundland. With the arrival of the Norwegians, the modern era of commercial shore-station whaling began.