‘More than a song’: the enduring power of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah

In a new documentary, fans and experts explore the legacy of a song originally shunned before becoming a timeless classic

Wed 29 Jun 2022 07.19 BST

Last modified on Wed 29 Jun 2022 22.17 BST“I can’t think of another song with a trajectory of anything like what happened with Hallelujah,” said the author Alan Light of Leonard Cohen’s ubiquitous magnum opus. “When you think of universal global anthems like Imagine or Bridge Over Troubled Water, they were immediate hits. But Hallelujah was first rejected by the record company, and then completely ignored when it came out.”

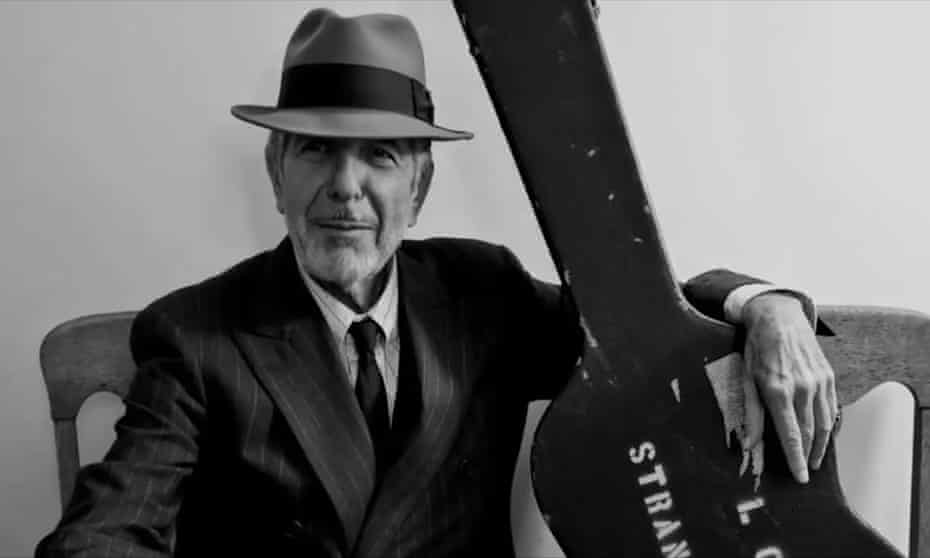

So goes the legend of Cohen’s hallmark track, which has captivated generations of listeners with a mystique and weight that set it apart. Perhaps that’s why the aforementioned Light wrote a book entirely about the track: 2012’s The Holy Or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and the Unlikely Ascent of Hallelujah. It’s that book which serves as the basis for the new documentary Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival earlier this month. Directed and produced by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller, the film takes both a micro and macro view of the song and Cohen, along with their respective and deeply intertwined places in culture.

“Leonard Cohen, in short, was a prophet,” said Goldfine, who, along with Geller, has assembled a stacked career directing expansive documentaries focusing on music including 2005’s Ballets Russes, about the early 20th-century Russian ballet company. “Leonard [was known for] timeless writing and timeless poetry that floats outside of any particular epoch,” Goldfine said. “It addressed the deepest of our human concerns about longing for connection and longing for some sort of hope, transcendence and acknowledgment of the difficulties of life.”

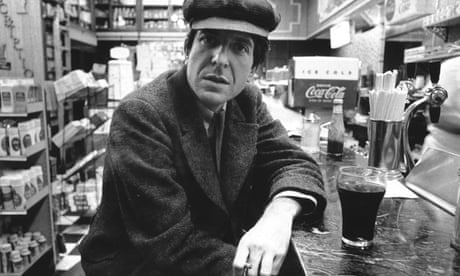

While Hallelujah may sound like an old standard, or some ancient hymn passed down through the ages, it was actually written in 1983 using a measly electric Casio keyboard. “There isn’t another songwriter like Cohen,” says Light, of the language Cohen brought to his art. “His approach to language and craft feel unlike the work of anybody else. And they sound rooted in poetry and literature because he studied as a poet and a novelist first.” Cohen wrote ceaselessly, writing a reported 180 verses alone for Hallelujah during the writing process. Adding to its inherent drama are the original version’s deep vocals, with Cohen’s voice deepened after years of cigarette smoking.

But it was Columbia Records, in a choice akin to Decca Records turning down the then fledgling Beatles for a record contract in 1962, who made the decision that Hallelujah and the album it came from, Various Positions, didn’t have the commercial cachet they were seeking. As the documentary chronicles, Cohen was crushed and it was eventually released by an independent label. “Leonard looked with a certain amazement and amusement that this song that had been cast off and spurned by his record label went on to become his signature song,” says Light of Cohen’s reaction to its later success. “He talked several times about feeling a sense of revenge or justice about how the song was later recognized and regarded.” Cohen’s version didn’t register on the Billboard charts until his death in 2016 at 82.

Why Hallelujah reached the heights it did is due to a unique mix of inventive cover versions, cultural happenstance and a magic-in-a-bottle quality the song no doubt possesses. Search the track on Spotify today and it’s Jeff Buckley’s version, not Cohen’s, which is the top result; the pairing of the song’s seemingly haunting subject matter and Buckley’s raw 1994 recording, coupled with the singer-songwriter’s drowning death aged just 30, adds another layer of weight. Buckley’s version was inducted into the Library of Congress’s national registry in 2013. Then there’s John Cale’s popular take on the tune, the first artist to cover the track in 1991.

But oddly enough, the song’s modern ubiquity can be traced to its prominent placement in Shrek, the second-highest grossing movie of 2001, which effectively launched Hallelujah into the upper echelons of popular culture. (The film features Cale’s version while the soundtrack includes Rufus Wainwright’s cover). Perhaps it’s fitting that an animated comedy would propel Cohen’s legend, considering that according to Geller the biggest misconception about Cohen himself is that he was originally considered the singer of gloom and doom. “Instead, we found a man who was so funny and so dry,” Geller explained. “Almost everything he said came out with a twinkle in his eye.”

In recent years, Hallelujah has had dozens of placements in TV and movies (from Scrubs to Zack Snyder’s Justice League) and has been sung by everyone from Bob Dylan to Bono, Brandi Carlile to Il Divo. The comedian Kate McKinnon sang it in character as Hillary Clinton to open the first episode of Saturday Night Live following the 2016 election of Donald Trump. Meanwhile, last year Yolanda Adams performed her take on National Covid Remembrance Day at the Lincoln Memorial. That’s not to mention the plethora of singing competition contestants from The X Factor to American Idol who sang of majors and minors falling, for better or for worse.

“It’s a Rorschach test,” says Light of the various interpretations of its lyrics, including the idea that it’s meant to be a Christian song. In reality, as the film chronicles, Cohen was Jewish. “The word Hallelujah appears across religions and faiths. Even though clearly Leonard’s own Judaism informs so much of what he put into the song, it’s one that people take what they need from it and what they want it to be. I think that’s why it’s played everywhere from weddings to funerals and births.” Adds Geller of Cohen’s musical output: “He has these lyrics and very beautiful musical arrangements that step out of time and can last and be relevant for audiences of all ages.”

For the film-makers, it was footage of Cohen singing Hallelujah on stage during a performance in Oakland, California, that partly inspired them to concoct the documentary. “I just couldn’t stop thinking of it,” says Goldfine. “It is more than a song. [This is a] documentary about one’s own center, and one’s own role and place in life.”

Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, A Journey, A Song is out in US cinemas on 1 July, Australian cinemas on 14 July, and in the UK later this year

… as you’re joining us today from Canada, we have a small favour to ask. Tens of millions have placed their trust in the Guardian’s fearless journalism since we started publishing 200 years ago, turning to us in moments of crisis, uncertainty, solidarity and hope. More than 1.5 million supporters, from 180 countries, now power us financially – keeping us open to all, and fiercely independent.

Unlike many others, the Guardian has no shareholders and no billionaire owner. Just the determination and passion to deliver high-impact global reporting, always free from commercial or political influence. Reporting like this is vital for democracy, for fairness and to demand better from the powerful.

And we provide all this for free, for everyone to read. We do this because we believe in information equality. Greater numbers of people can keep track of the events shaping our world, understand their impact on people and communities, and become inspired to take meaningful action. Millions can benefit from open access to quality, truthful news, regardless of their ability to pay for it.