|

UNITED STATES COMMISSION OF FISH AND FISHERIES.PART IV.REPORTOFTHE COMMISSIONERFOR1875–1876.A – INQUIRY INTO THE DECREASE OF THE FOOD-FISHES. |

HISTORYOF THEAMERICAN WHALE FISHERYFROMITS EARLIEST INCEPTION TO THE YEAR 1876.BYALEXANDER STARBUCK.PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR.Waltham, Mass.1878. |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

B. – ACCOUNT OF THE WHALE-FISHERY from 1600 to 1700:

|

C. – WHALE-FISHERY from 1700 to 1750:

|

705

D. – WHALE-FISHERY from 1750 TO 1784 – Continued.

|

D. – WHALE-FISHERY from 1750 TO 1784 – Continued.

* The latitude is misprinted in the note. |

E. – WHALE-FISHERY from 1784 TO 1816 – Continued.

|

E. – WHALE-FISHERY from 1784 TO 1816 – Continued.

F. – THE DANGERS OF THE WHALE FISHERY:

|

G. – MISCELLANEOUS – Continued.

H. – INTRODUCTORY TO RETURNS, 166. I. – RETURNS OF WHALING VESSELS from 1715 to 1784, 168. Note: The tabular returns for whaling vessels have not been created for this transcription. Instead, links to the relevant pages in one of the Starbuck editions available via Google Books are found below. Access to Starbuck's Tables Showing |

Selecting the links below will result in the opening of a separate screen. These screens will have to be closed separately as you proceed. |

J. – SUMMARY OF IMPORTATION OF OIL AND BONE from January 1, 1804, to January 1, 1887, 660.

K. – SYNOPSIS OF IMPORTATION, BY PORTS, from 1804 to 1877, with the nature and number of vessels returning, and (from 1839) the class and tonnage of vessels engaged, 662.

L. – EXPORTS FROM THE UNITED STATES, the products of the whale-fishery, from 1791 to July 1, 1876, 700.

Table via Google Books.M. – TONNAGE OF VESSELS ENGAGED IN THE WHALE FISHERY, 702.

M. – AGGREGATE YEARLY TONNAGE OF VESSELS ENGAGED IN THE WHALE-fishery from 1794 to 1816, and from 1818 to 1839, 702. N. – SPECIAL TABLE OF THE YEARLY TONNAGE OF VESSELS ENGAGED IN whaling from New Bedford and Fairhaven from 1820 to 1839, 702. INDEX TO VOYAGES BY VESSELS; names arranged alphabetically, and towns also in alphabetical order, 711. GENERAL ALPHABETICAL INDEX, 764. ERRATA. Page 322. Include both entries to Imogene of Provincetown in one. |

I. HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN WHALE FISHERY FROM ITS EARLIEST INCEPTION TO THE YEAR 1876 *By Alexander StarbuckA. – INTRODUCTION.Few interests have exerted a more marked influence upon the history of the United States than that of the fisheries. Aside from the value they have had in a commercial point of view, they have always been found to be the nurseries of a hardy, daring, and indefatigable race of seamen, such as scarcely any other pursuit could have trained. The pioneers of the sea, whalemen were the advance guard, the forlorn hope of civilization. Exploring expeditions followed after to glean where they had reaped. In the frozen seas of the north and the south, their keels plowed to the extreme limit of navigation, and between the tropics * More than fifty years ago (in 1815) Samuel'H. Jenks, esq., then editor of the Nantucket Inquirer, announced his intention to write the history of whaling, and advertised for material for that purpose, but so little encouragement did he meet, so little material came to hand, that he finally abandoned the design in despair of ever being able to satisfactorily complete it. In the preface to his admirable Report on the Fisheries, published in 1852, Hon. Loenzo Sabine says: " Most] than twenty years have elapsed since I formed the design of writing a work on the American fisheries, and commenced collecting materials for the purpose. My intention embraced the whale-fishery of our flag in distant seas. But increasing cares prevented the consummation of his plans. The difficulties in the way of collection of historical notes increase greatly with the lapse of years. Newspapers, which must always be considered, where they exist, invaluable aids in the prosecution of such matters, pass from the possession of the very few who, when living, treasured them, and fall into the hands of those who only value them at so many cents per pound. Those who were the actors in the scenes which it Is desired to describe die, and with them perishes the source of the information, which ultimately, in the form of tradition, becomes too distorted to be available. In the matter of the whale-fishery still another formidable difficulty is met with, in the absence or destruction of customs-records. During the Revolution many ports were under English control, and very often with the departure of the British also departed the customhouse papers. In other ports, notably Now Bedford and Nantucket, these records have been destroyed by fire. Still again in yet other ports, notably Sag Harbor, mildew and decay have obliterated the writing. About eighteen months ago Prof. Spencer F. Baird, United States Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries, requested the writer to prepare a historical sketch of this indus- |

they pursued their prey through regions never before traversed by the vessels of a civilized community. Holding their lives in their hands, as it were, whether they harpooned the leviathan in the deep, or put into some hitherto unknown port for supplies, no extreme of heat or cold could daunt them, no thought of danger hold them in check. Their lives have ever been one continual round of hair-breadth escapes, in which the risk was alike shared by officers and men. No shirk could find an opportunity to indulge his shirking, no coward a chance to display his cowardice, and in their hazardous life incompetents were speedily weeded out. Many a tale of danger and toil and suffering, startling, severe, and horrible, has illumined the pages of the history of this pursuit, and scarce any, even the humblest of these hardy mariners, but can, from his own experience, narrate truths stranger than fiction. In many ports, among hundreds of islands, on many seas the flag of the country from which they sailed was first displayed from the mast-head of a whale ship. Pursuing their avocation wherever a chance presented, the American flag was first unfurled in an English port from the deck of one American whaleman, and the ports of the western coast of South America first beheld the Stars and Stripes shown as the standard of another. It may be safely alleged that but for them the western try, so far as it related to our own country, and append to it, so far as was practicable, a record of every voyage which has been performed. Of the magnitude of this labor only those who have had similar experience can form any idea. In the one item of marine reports, it comprehended the examination of newspapers covering a period of one hundred and seventy years. The limited time allowed for the work performed is not mentioned l y the writer in any spirit of self -laudation, but as a statement due to himself for any possible errors of omission or commission that may have occurred. Fortunately in the collection of material for a work of an entirely different nature much bad been gathered which had a hearing upon this subject, and much that was absolutely necessary for use in this connection, and, fortunately, the kindness of many friends lightened still more the labor. Wherever the writer has been in search of material the utmost courtesy has been extended, and, with very rare exceptions, whenever application has been made, books and documents have been freely placed at his command. Especially is he under obligations to Charles Eldridge, esq., of Fairhaven; Dennis Wood, esq., the proprietor of the Shipping-List; and R. C. Ingraham, esq., of New Bedford; the late William R. Sleight, esq., of Sag Harbor, N. Y.; the late Hon. Henry P. Haven, and Haven, Williams & Co., of New London, Conn.; Benjamin F. Cook, esq., of Now York; Hon. Lorenzo Sabine, of Boston (who kindly placed all his papers on the subject at the author's disposal) ; F. C. Sanford, J. S. Barney, and W. H. Macy, esqrs., and Miss R. A. Gardner, of Nantucket ; Maj. S. B. Phinney, of Barnstable; R. L. Pease, esq., of Edgartown; Capt. Silas Jones, of Falmouth ; Capt. S. W. Macy, of Newport, R. I.; B. Furnald, esq., custodian of historical records of New York (see numerous quotations, the result mainly of his indefatigable researches); and the collectors and assistants of the ports of Boston and New Bedford. He also acknowledges courtesies from those in charge of the libraries of the Massachusetts Historical, Boston Athen:num, and American Antiquarian Societies. If in the search for facts the historical idols of others have been shattered, it may be a source of satisfaction to them to learn that the writer has been equally iconoclastic with many that he too has reverenced. ALEXANDER STARBUCK. Waltham, Mass., March 1, 1877. |

oceans would much longer have been comparatively unknown,* and with equal truth may it be said that whatever of honor or glory the United States may have won in its explorations of these oceans, the necessity for their explorations was a tribute wrung from the Government, though not without earnest and continued effort, to the interests of our mariners, who, for years before, had pursued the whale in these uncharted seas, and threaded their way with extremest care among these undescribed islands, reefs, and shoals. Into the field opened by them flowed the trade of the civilized world. In their footsteps followed Christianity. They introduced the missionary to new spheres of usefulness, and made his presence tenable. Says a writer in the London Quarterly Review: "The whale fishery first opened to Great Britain beneficial intercourse with the coast of Spanish America; IT LED IN THE SEQUEL TO THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE SPANISH COLONIES." * * * * * "But for our Whalers, we never might have founded our colonies in Van Dieman's Land and Australia – or if we had we could not have maintained them in their early stages of danger and privation. – Moreover, our intimacy with the Polynesians must be traced to the same source. The Whalers were the first that traded in that quarter – they PREPARED THE FIELD FOR THE MISSIONARIES; and the same thing is now in progress in New Ireland, New Britain, and New Zealand." All that the English fishery has done for Great Britain, the American fishery has done for the United States – and more. In war our Navy has drawn upon it for some of its sturdiest and bravest seamen, and in peace our commercial marine has found in it its choicest and most skilful officers. In connection with the cod-fishery it schooled the sons of America to a knowledge of their own strength, and in its protection developed and intensified that spirit of self-reliance, independence, and national power to which the conflict of from 1775 to 1783 was a natural and necessary resultant. The wars carried on between England and France from 1600 * The North American Review, in 1834, in an article on the Whale Fishery, says, "A few years since, two Russian discovery ships came in sight of a group of cold, inhospitable islands in the Antarctic Ocean. The commander imagined himself a discoverer, and doubtless was prepared with drawn sword and with the flag of his sovereign flying over his bead to take possession in the name of the Czar. At this time he was becalmed in a dense fog. Judge of his surprise, when the fog cleared away, to see a little sealing sloop from Connecticut as quietly riding between his ships as if lying in the waters of Long Island Sound. He learned from the captain that the islands were already well known, and that he had just returned from exploring the shores of a new land at the south ; upon which the Russian gave vent to an expression too hard to be repeated, but sufficiently significant of his opinion of American enterprise. After the captain of the sloop, be named the discovery 'Palmer's Land,' in which the American acquiesced, and by this name it appears to be designated on all the recently-published Russian and English charts." A similar experience awaited the English ship Caribou, Captain Cabins, who came in sight of Hurd's Island, and, like the Russian, thought it hitherto unknown land. The similarity was carried still further by the appearance of the schooner Oxford, of Fairhaven (tender to the Arab), the captain of which informed him that the island was discovered by them eighteen months before. |

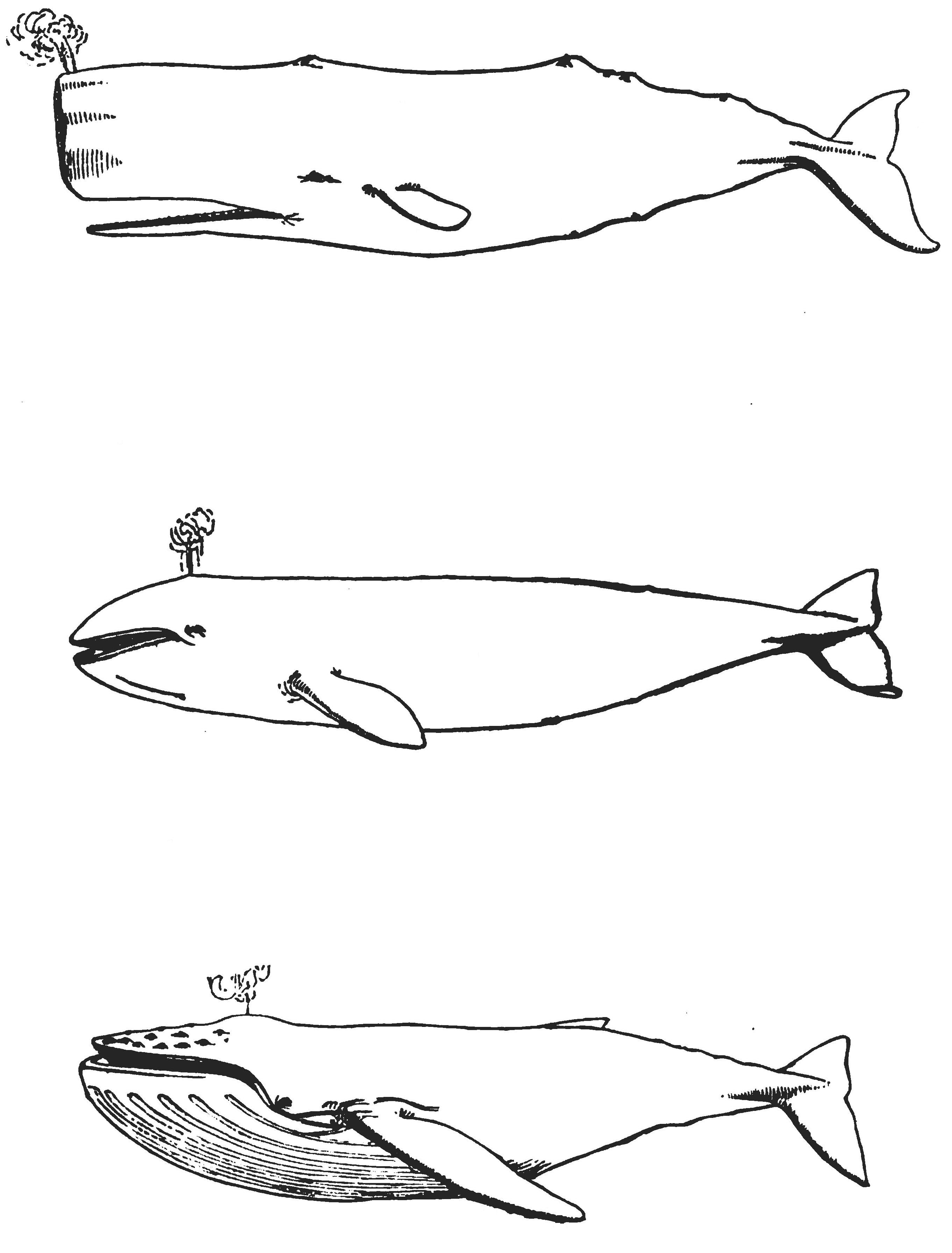

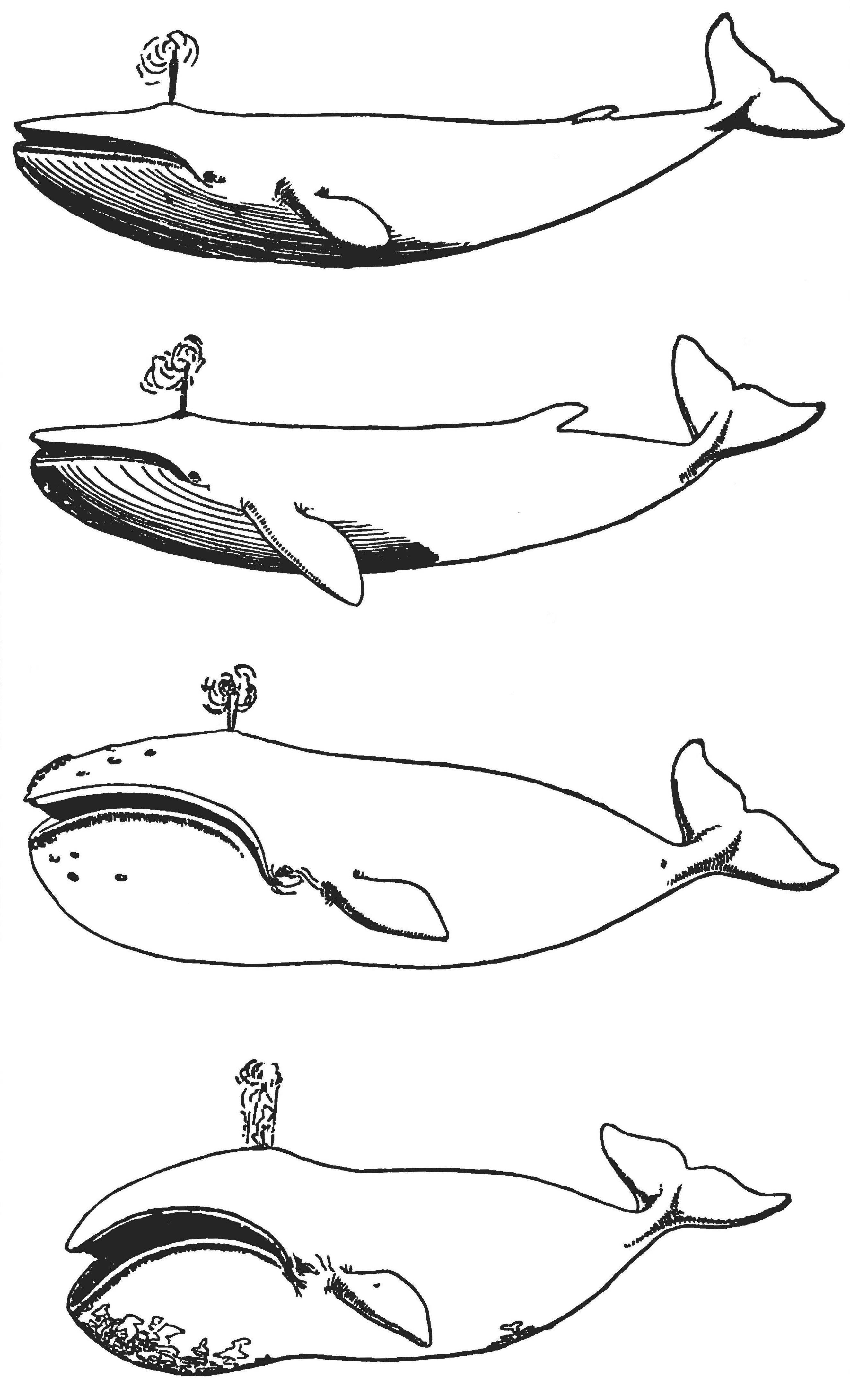

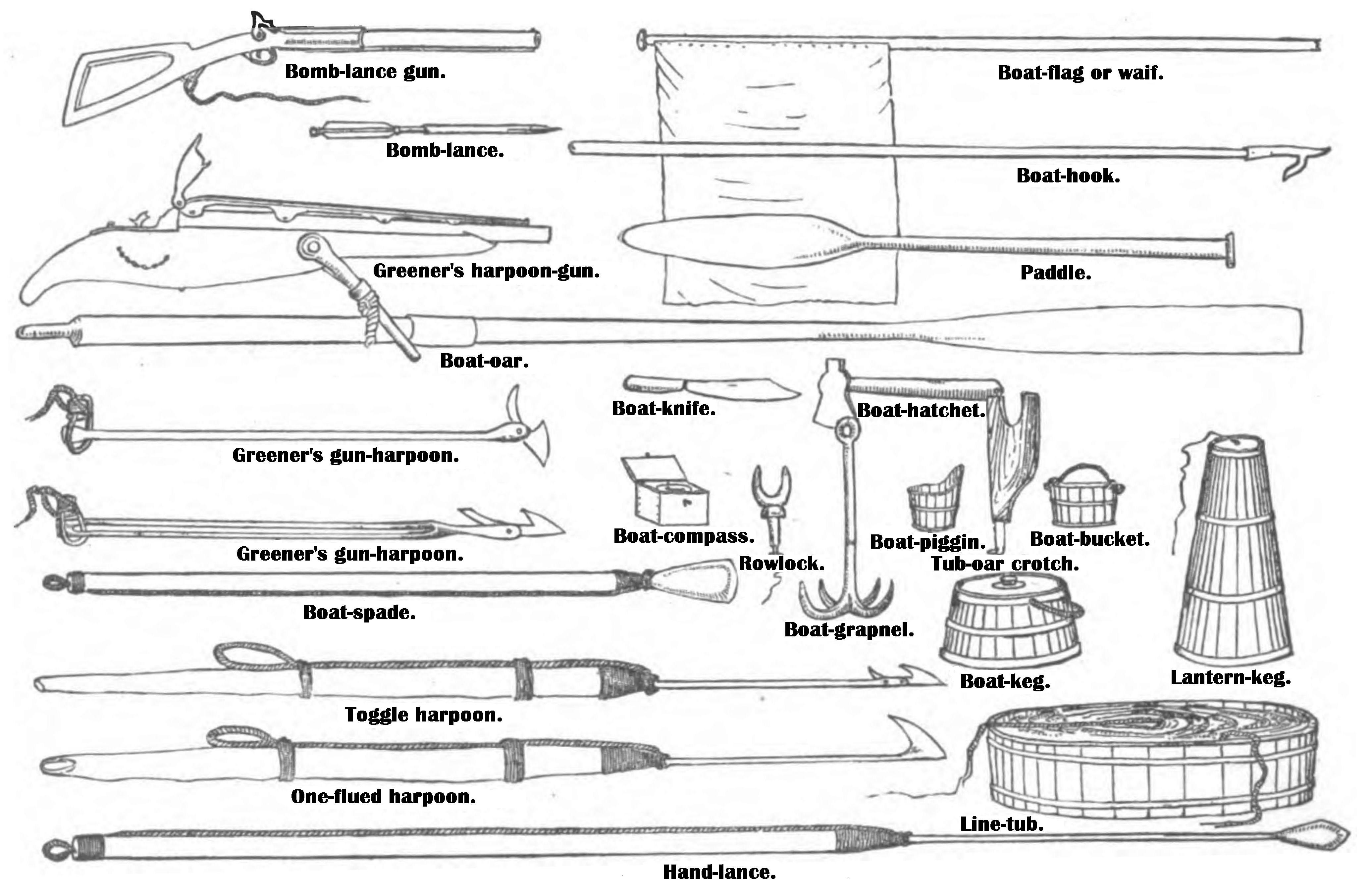

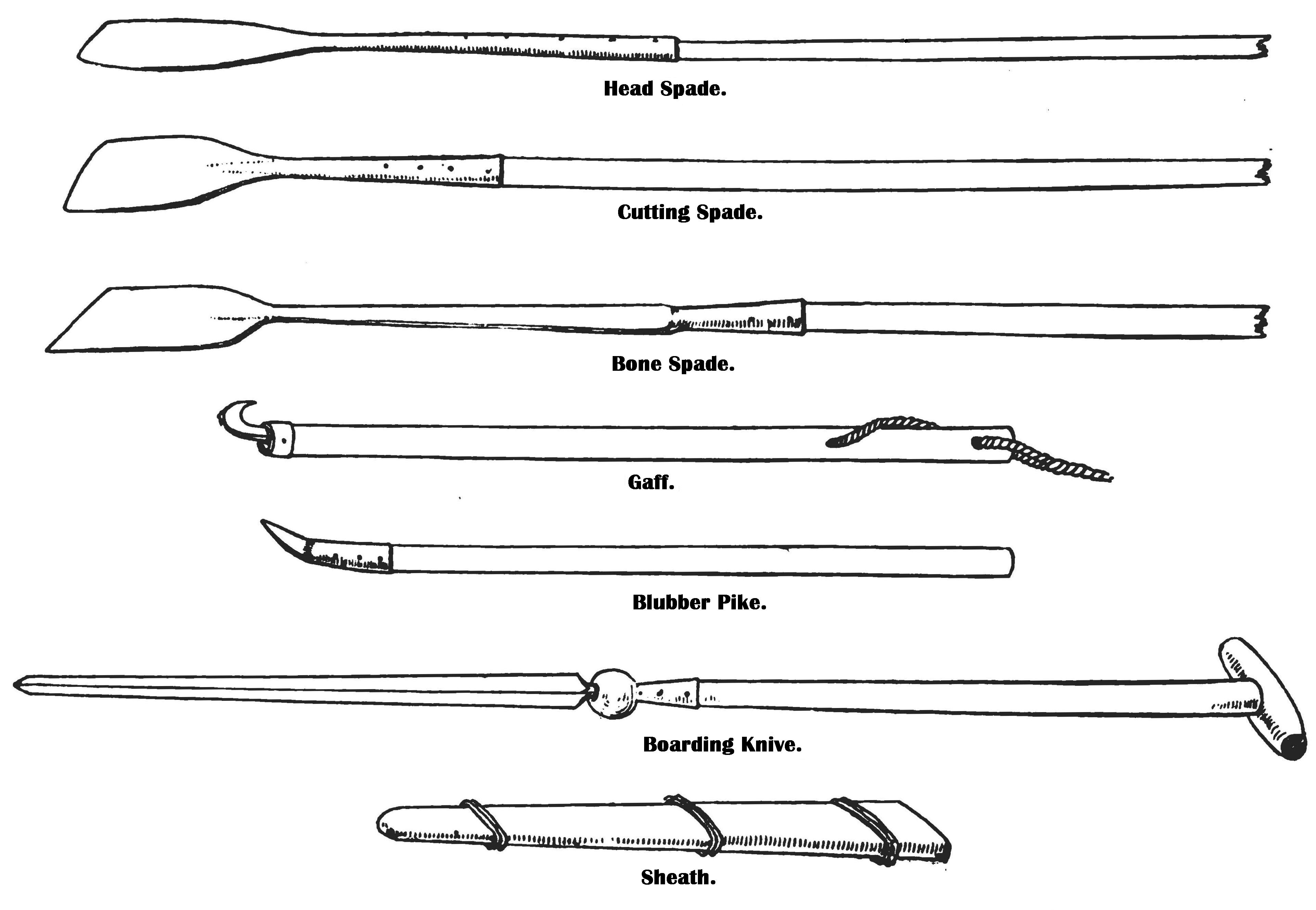

oil and bone came daily alongside and played about the ship. The master and his mate, and others experienced in fishing, preferred it to the Greenland whale fishery, and asserted that were they provided with the proper implements, £300 or £400 worth of oil might be obtained?" 4th. The situation was healthy, secure, and defensible. 5th. It was in the depth of winter and inexpedient to look further.* Coming from England, as the vast majority of the early settlers did, where the value of the fisheries had already assumed considerable importance, it would have been strange if they had failed to have appreciated this important feature of their surroundings. At this time the whales were very numerous both along the coast and in deep water.† Their habits seem to have been somewhat migratory, as the boat-whaling season usually commenced very regularly early in November and ceased in March or April. According to some writers, the Indians, before the advent of the whites, were accustomed to pursue the whales in their canoes, and occasionally succeeded in harassing them to death. Their weapons consisted of a rude wooden harpoon, to which was attached a line with a wooden float at the end,‡ and the method of attack was to plunge their instruments of torture into the body of the whale whenever he came to the surface of the water to breathe. In Waymouth's journal of his voyage to America in 1605,§ in describing the Indians on the coast, he says: "One especial thing is their manner of killing the whale, which they call powdawe; and will describe his form; how he bloweth up the water; and that he is twelve fathoms long and that they go in company of their king with a multitude of their boats; and strike him with a bone made in fashion of a harping iron fastened to a rope, which they make great and strong of the bark of trees, which they veer out after him; then all their boats come about him as he riseth above water, with their arrows they shoot him to death; when they have killed him and dragged him to shore, they call all their chief lords together, and sing a song of joy: and those chief lords, whom they call sagamores, divide the spoil and give to every man a share, which pieces so distributed, they hang up about their houses for provisions; and when they boil them they blow off the fat and put to their pease, maize, and other pulse which they eat." Among the Indians of Rhode Island it was the custom when a whale was cast ashore or killed within their jurisdiction, to cut the flesh into pieces and send to the * Thatcher's list. of Plymouth, p. 21. † Capt. John Smith, in 1614, found whales so plentiful along the coast that he turned aside from the primary object of his voyage to pursue them. Richard Mather, who came over to the Massachusetts Bay in 1635, records in his journal of the voyage seeing near New England " mighty whales spewing up water in the air, like the smoke of a chimney, and making the sea about them white and hoary, as is said in Job, of such incredible bigness that I will never wonder that the body of Jonas could be in the belly of a whale." (Sabine's Report, p. 42.) ‡ "Etchings of a Whaling Cruise," Browne, p. 522. § Mass. Hist. Soc. Coll., iii series, viii vol., 156 p. |

neighboring tribes as a present of peculiar value.* Scammon says:† "It has been stated by several writers that the American colonists followed up the Indian mode of capturing the whale, by first striking it with a harpoon having a log of wood attached to it by a line, even as late as the commencement of the Sperm Whale fishery." It is quoted that the Hon. Paul Dudley stated: "Our people formerly used to kill the whale near the shore, but now they go off to sea in sloops and whale-boats. Sometimes the whale is killed by a single stroke, and yet at other times she will hold the whalemen in play near half a day together, with their lances; and sometimes they will get away after they have been lanced and spouted thick blood, with irons in them, and drags (droges) fastened to them, which are thick boards about fourteen inches square." * * * "We are of the opinion, however, that the colonial whalers did not follow the Indian mode of whale-fishing; for it is well known that the British whalers, as early as 1670, used the line attached to the boat, and, so far as the drags or 'droges' are concerned, they are used at the present day in cases of emergency.‡ As early as 1639, Massachusetts, with an eye to the importance of the fisheries, passed an act to encourage them. By its provisions all vessels employed in taking or transporting fish were exempted from all duties and taxes for the term of seven years, and all fishermen were exempted from military service during the fishing season. As important as the pursuit of whaling seemed to have been considered by the first settlers, many years seem to have elapsed before it was followed as a business, though probably something was attempted in that direction prior to any recorded account that we have. The subject of drift-whales appears to have attracted considerable importance both in the Plymouth and the Massachusetts Bay colonies. The colonial government claimed a portion, a portion was allowed to the town, and the finder, if no other * Arnold's Hist. R. I., i, p. 65. Among the Montauk Indians the most savory sacraflee to their deity was the tail or flu of the whale. (Hedge's Address, p. 35.) The Greenlander's idea of Heaven, according to Father Hcnnepin, was a place where there would be an immense cauldron continually boiling, and each could take as much seal blubber, ready cooked, as he wanted. † Marine Mammalia and American Whale Fishery, p. 204, note. ‡ It would appear from Purchas' account that lines were used to attach the boat to the whale as early as 1613. He writes: "I might hero recreate your wearied eyes with a hunting spectacle of the greatest chase which nature yieldeth; I mean the killing of a whale. When they espy him on the top of the water (which he is forced to for to take breath), they row toward him in a shallop, in which the harponcer stands ready with both his hands to dart his harping iron, to which is fastened a line of such length that the whale (which suddenly feeling himself hurt, sinketh to the bottom,) may carry it down with him, being before fitted that the shallop be not therewith endangered; coming up again, they strike him with lances made for that purpose, about twelve feet long, the iron eight thereof, and the blade eighteen inches-the harping iron principally serving to fasten hint to the shallop, and thus they hold him in such pursuit, till after streams of water, and next of blood, cast up into the air and water, (as angry with both elements, which have brought thither such weak hands for his destruction,) be at length yieldeth tip his slain carcass as weed to the conquerors." |

claimant appeared to dispute his title, might presume to claim the other third. Evidently at times some disposition to rebel was manifested, for in 1661, the general court of Plymouth Colony sent to Sandwich, Barnstable, Yarmouth, and Eastham the following proposition: "Oct. 1, 1661. – Loueing Frinds: Whereas the Generall Court was pleased to make some proposition to you respecting the drift fish or whales; in case you should refuse theire proffer, they impowered mee, though vnfitt, to farme out what should belonge vnto them on that account; and seeing the time is expired, and it fales into my hands to dispose of, I doe therefore, with the advice of the Court, in answare to your remonstrance, say, that if you will duely and trewly pay to the countrey for euery whale that shall come one hogshead of oyle att Boston, where I shall appoint, and that current and merchantable, without any charge or trouble to the countrey.* – I say, for peace and quietness sake you shall have it for this present season, leaueing you and the Election Court to settle it soe as it may bee to satisfaction on both sides; and in case you accept not of this tender, to send it within fourteen dayes after the date heerof and if I heare not from you, I shall take it for graunted that you will accept of it, and shall expect the accomplishment of the same. "Youers to vse, "CONSTANT SOUTHWORTH TREASU."† The offer was accepted and indorsed as follows: "The sixt of the first month 61-62. "Agreement to give 2 bbls of oyle from each whale according to proposition made for yeare past, to end all troubles. "ANTHONY THACHER. "ROBERT DENIS. "THOMAS BOARDMAN. "RICHARD TAYLER." Numerous instances of orders relating to drift-whales occur in the records of Plymouth, Massachusetts, and New York. In 1662, the town of Eastham voted that a part of every whale cast ashore should be appropriated for the support of the ministry.‡ Many were the disputes that the general court was called upon to adjust in regard to stranded whales, but the decisions seem to be, if not generally satisfactory, at least universally acquiesced in. The earliest account of whale-killing by the people of Cape Cod comes to us in the form of a tradition, and quite an unsatisfactory and improba- * By an order of court, June 6, 1654, whales cast up on lands of purchasers belonged to said proprietors. (Plym. Col. Rec. iii, p. 53.) This being much more satisfactory than the order compelling tribute to the government, probably caused ill-feeling when the general court preferred a claim. † Plym. Col. Rec., vol. iv, p. 6. ‡ Freeman's Hist. Cape Cod, ii, p. 362. |

ble tradition, too. It is to the effect that one William Hamilton was the first to kill these fish from that region, and be was obliged to remove from that section of country, as his fellow-citizens persecuted him for his skill, attributing his success to undue familiarity with evil spirits. Hamilton is said to have removed to Rhode Island, and from thence to Connecticut, where he died in 1746, aged 103 years. Several things militate against this story. Neither the annals of the Cape* nor genealogical registers contain any record of him. Naturally the courts would take some cognizance of an offense so heinous that the offender was openly persecuted, but we do not find him noted as a criminal. The people who settled on the Cape were too familiar with fishing to attribute success to aught but skill and natural causes, and the Cape was more an asylum for the persecuted than the source of persecution. It is far more probable that at the time of his birth, if he ever existed there, there were people familiar with this art in that region. It had certainly become a pursuit of much importance in other sections of the country long before he was old enough to handle a harpoon, and the product of this fishery had found its way to Boston while he was yet a young man. In 1683 Secretary Randolph writes home from Massachusetts: "New Plimouth Colony have great profit by whale killing. I believe it will be one of our best returnes, now beaver and peltry fayle us."† In March of the same year there was placed on the colonial records of Massachusetts Bay a memorandum embodying the universally recognized law of whalemen that "craft claims the whale." It specifies: "furst: if aney pursons shall find a Dead whael on the streem And have the opportunity to toss herr on shoure; then ye owners to alow them twenty shillings; 2ly: if thay cast hur out & secure ye blubber & bone then ye owners to pay them for it 30s (that is if ye whael ware lickly to be loast;) 3ly, if it proves a floate son not killed by men then ye Admirall to Doe thaire in as he shall please; — 4ly; that no persons shall presume to cut up any whael till she be vewed by toe persons not consarned; that so ye Right owners may not be Rongged of such whael or whaels; 5ly, that no whael shall be needlessly or fouellishly lansed behind ye vitall to avoid stroy; 6ly, that each companys harping Iron & lance be Distinckly marked on ye heads & socketts with a poblick mark: to ye prevention of strife; 7ly, that if a whale or whalls be found & no Iron in them: then thay that lay ye neerest claime to them by thaire strokes & ye natoral markes to haue them; 8ly, if 2 or 3 companyes lay equal claimes, then thay eqnelly to shear."‡ In November, 1690, the colony of New Plymouth appointed "Inspectors of Whale," in order to the "prevention of suits by whalers." The * It is scarcely probable that so careful a historian as Freeman would have omitted to make mention of Hamilton, if this story of him had any foundation in fact. † Hutchinson's Coll., p. 558. ‡ Mass. Col. MSS., Treasury, iii, p. 80. |

rules governing them were:" 1. All whales killed or wounded & left at sea the killers to repaire to the inspectors & give marks, time, place, which shall be recorded. 2. All whales brought or cast ashore to be viewed by inspector or deputy before being cut & marks & wounds recorded with time & place. 3. Any person cutting or defacing whale before being viewed unless necessary shall lose right to it, & pay 10£ to county, & fish to be seized by inspectors for owners' use. Inspectors to have power to make deputy and allow 6s. per whale. 4. Those finding whale a mile from shore not appearing to be killed by man shall be first to secure them, pay 1 hogshead of oyle to ye county for each whale."* In 1647 (May 25) at a meeting of the general court held at Hartford, Conn., the following resolve was passed: "Yf Mr. Whiting, wth any others shall make tryall and prsecute a designe for the takeing of whale wthin these libertyes, and if vppon tryall wthin the terme of two yeares, they shall like to goe on, noe others shalbe suffered to interrupt the, for the tearme of seauen yeares."† Whether Mr. Whiting, who seems to have been quite a prominent man and a merchant at Hartford, ever did "prosecute his designe," or not, we are left to conjecture; but so far as we at present know, this is the earliest official document showing any intention in that direction, and many years elapse before Connecticut again claims attention upon this subject. It is probably safe to assert that the first organized prosecution of the American whale-fishery was made along the shores of Long Island. The town of Southampton, which was settled in 1640 by an offshoot from the Massachusetts Colony at Lynn,‡ was quick to appreciate the value of this source of revenue. In March, 1644, the town ordered the town divided into four wards of eleven persons to each ward, to attend to the drift-whales cast ashore. When such an event took place two persons from each ward (selected by lot) were to be employed to cut it up. "And every Inhabitant with his child or servant that is above sixteen years of age shall have in the Division of the other part," (i. e. what remained after the cutters deducted the double share they were, ex officio, entitled to) "an equall proportion provided that such person when yt falls into his ward a sufficient man to be imployed aboute yt."§ Among the names of those delegated to each ward are many whose descendants became prominent in the business as masters or owners of vessels – the Coopers, the Sayres, Mulfords, Peirsons, Hedges, Howells, Posts, and others. A few years later the number of "squadrons" was increased to six. * Plym. Col. Rec. vi, pp. 252-3. † Conn. Col. Rec., i, p. 154. ‡ Southampton was settled under a patent from the Earl of Sterling, and the privileges accorded were essentially those of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1664 the commissioners to adjust the colonial bounds decided this and the adjacent towns to be within the jurisdiction of the Duke of York. § Howell's Hist. of Southampton, p. 179. |

In February, 1645, the town ordered that if any whale was cast ashore within the limits of the town no man should take or carry away any part thereof without order from a magistrate, under penalty of twenty shillings. Whoever should find any whale or part of a whale, upon giving notice to a magistrate, should have allowed him five shillings, or if the portion found should not be worth five shillings the finder should have the whole. "And yt is further ordered that yf any shall finde a whale or any peece thereof upon the Lord's day then the aforesaid shillings shall not be due or payable."* "This last clause" says Howell, "appears to be a very shrewd thrust at 'mooning' on the beach on Sundays." It was customary a few years later to fit out expeditions of several boats each for whaling along the coast, the parties engaged camping out on shore during the night. These expeditions were usually gone about one or two weeks.† Indians were usually employed by the English, the whites furnishing all the necessary implements, and the Indians receiving a stipulated proportion of oil in payment. In Easthampton on the 6th of November, 1651, "It was Ordered that Goodman Mulford shall call out ye Town by succession to loke out for whale"‡ Easthampton, however, like every other town where whales were obtainable, seems to have had its little unpleasantnesses on the subject, for in 1653 the town "Ordered that the share of whale now in controversie between the Widow Talmage and Thomas Talmage" (alas for the old-time Chesterfieldian gallantry) "shall be divided among them as the lot is."§ In the early deeds of the town the Indian grantors were to be allowed the fins and tails of all drift-whales; and in the deed of Montauk Island and Point, the Indians and whites were to be equal sharers in these prizes.¡ In 1672 the towns of Easthampton, Southampton, and Southwold presented a memorial to the court at Whitehall "setting forth that they have spent much time and paines, and the greatest part of their Estates, in settling the trade of whale-fishing in the adjacent seas, having endeavoured it above these twenty yeares, but could not bring it to any perfection till within these 2 or 3 yeares last past. And it now being a hopefull trade at New Yorke, in America, the Governor and the Dutch there do require ye Petitioners to come under their patent, and lay very heavy taxes upon them beyond any of his Maties subjects in New England, and will not permit the petitioners to have any deputys in Court,¶ but being chiefe, do impose what Laws they please upon them, and insulting very much over the Petitioners threaten to cut down their timber which is but little they have to Casks for oyle, altho' the Petrs purchased their landes of the Lord Sterling's deputy, above 30 yeares since, and have till now under the Government and Pat- * Ibid., p. 184. † Ibid., p. 183. ‡ Bi-Centennial Address at Easthampton, 1850, by Henry P. Hedges, p. 8. § Ibid., p. 8. ¡ Ibid. ¶ In this petition is an early assertion of the twiuship of taxation and representation, for which Massachusetts and her offshoots were ever strenuous. |

ent of Mr. Winthrop, belonging to Conitycut Patent, which lyeth far more convenient for ye Petitioners assistance in the aforesaid Trade." They desire, therefore, either to continue under the Connecticut government, or to be made a free corporation. This petition was referred to the "Council on Foreign Plantations." This would make the commencement of this industry date back not far from the year 1650. In December, 1652, the directors of the Dutch West India Company write to Director General Peter Stuyvesant, of New York: "In regard to the whale fishery we understand that it might be taken in hand during some part of the year. If this could be done with advantage, it would be a very desirable matter, and make the trade there flourish and animate many people to try their good luck in that branch.*" In April, (4th,) 1656, the council of New York "received the request of Hans Jongh, soldier and tanner, asking for a ton of train-oil or some of the fat of the whale lately captured.† In April, 1669, Mr. Samuel Mavericke writes to Colonel Nicolls:‡ "On ye Eastend of Long Island there were 12 or 13 whales taken before ye end of March, and what since wee heare not; here are dayly some seen in the very harbour, sometimes within Nutt Island. Out of the Pinnace the other week they struck two, but lost both, the iron broke in one, the other broke the warpe.§ The Governor hath encouraged some to follow this designe. Two shallops made for itt, but as yett wee doe not heare of any they have gotten?' In 1672, the town of Southampton passed an order for the regulation of whaling, which, in the latter part of the year, received the following confirmation from Governor Lovelace: "Whereas there was an ordinance made at a Towne-Meeting in South Hampton upon the Second Day of May last relating to the Regulation of the Whale ffishing and Employment of the Indyans therein, wherein particularly it is mentioned. That whosoever shall Hire an Indyan to go a-Whaling, shall not give him for his Hire above one Trucking Cloath Coat, for each whale, hee and his Company shall Kill, or halfe the Blubber, without the Whale Bone under a Penalty therein exprest: Upon Considerac'on had thereupon, I have thought good to Allow of the said Order, And do hereby Confirm the same, untill some inconvenience therein shall bee made appeare, And do also Order that the like Rule shall bee followed at East Hampton and other Places if they shall finde it practicable amongst them. "Given under my hand in New Yorke, the 28th of November, 1672. [Sign.] "FRAN: LOVELACE."¡ * N. Y. Col., MSS., vi, p. 75. † N. Y. Col., MSS., vi, p. 354. ‡ N. Y. Col., Rec. iii, p. 183. § It would seem by this that as early as 1669 American whaleman were accustomed to fasten to the whale with their line. ¡ N. Y. Col., MSS. |

Upon the same day that the people of Southampton passed the foregoing order, Governor Lovelace also issued an order citing that in consequence of great abuse to his Royal Highness in the matter of drift-whales upon Long Island, he had thought fit to appoint Mr. Wm. Osborne and Mr. John Smith, of Hempstead, to make strict inquiries of Indians and English in regard to the matter.* It was early found to be essential that all important contracts and agreements, especially "between the English and Indians relating to the killing of whales should be entered upon the town books, and signed by the parties in presence of the clerk and certified by him. Boat-whaling was so generally practiced and was considered of so much importance by the whole community, that every man of sufficient abilits in the town was obliged to take his turn in watching for whales from some elevated position on the beach, and to sound the alarm on one being seen near the coast."† In April, (2d,) 1668, an agreement was entered on the records of Easthampton, binding certain Indians of Montauket in the sum of £10 sterling to go to sea, whaling, on account of Jacobus Skallenger and others, of Easthampton, beginning on the 1st of November and ending on the 1st of the ensuing April, they engaging "to attend dilligently with all opportunitie for ye killing of whales or other fish, for ye sum of three shillings a day for every Indian: ye sayd Jacobus Skallenger and partners to furnish all necessarie craft and tackling convenient for ye designe." The laws governing these whaling-companies were based on justice rather than selfishness. Among the provisions was one passed January 4, 1669, whereby a member of one company finding a dead whale killed by the other company was obliged to notify the latter. A prudent proviso in the order was that the person bringing the tidings should be well rewarded. If the whale was found at sea, the killers and finders were to be equal sharers. If irons were found in the whale, they were to be restored to the owners.‡ In 1672, John Cooper desired leave to employ some "strange Indians" to assist him in whaling, which leave was granted;§ but these Indian allies required tender handling, and were quite apt to ignore their contracts when a fair excuse could be found, especially if their hands had already closed over the financial consideration. Two or three petitions relating to cases of this kind are on file at New York. One of them is from "Jacob Skallenger, Stephen Hand, James Loper and other adjoined with them in the Whale Designe at Easthampton," and was presented in 1675. It sets forth that they had associated together for the purpose of whaling, and agreed to hire twelve Indians and man two boats. Having seen the natives yearly employed both by neighbors and those in surrounding towns, they thought there could be no objec- * N. Y. Col., MSS., General Entries iv, p. 123, Francis Lovelace. † Howell's Southampton. ‡ This code was very similar to that afterward adopted in the Massachusetts Bay. § N. Y. Col. MSS.; General Entries, iv, p. 235. |

tion to their doing likewise. Accordingly, they agreed in June with twelve Indians to whale for them during the following season. "But it fell out soe that foure of the said Indians (competent & experienced men) belonged to Shelter-Island whoe with the rest received of your peticonrs in pt. of their hire or wages 25s. a peece in hand at the time of the contract, as the Indian Custome is and without which they would not engage themselves to goe to Sea as aforesaid for your Peticonrs." Soon after this there came an order from the governor requiring, in consequence of the troubles between the English and the aborigines, that all Indians should remain in their own quarters during the winter. "And some of the towne of Easthampton wanteing Indians to make up theire crue for whaleing they take advantage of your honrs sd Ordre thereby to hinder your peticonrs of the said foure Shelter-Island Indians. One of ye Overseers being of the Company that would soe hinder your peticonrs. And Mr. Barker warned yor peticonrs not to entertaine the said foure Indians without licence from your hour. And although some of your peticoners opposites in this matter of great weight to them seek to prevent yor peticonrs from haveing those foure Indians under pretence of zeal in fullfilling yr honrs order, yet it is more then apparent that they endeavor to break yor peticonrs Company in yt mater that soe they themselves may have opportunity out of the other eight Easthampton Indians to supply theire owue wants." After representing the loss liable to accrue to them from the failure of their design and the inability to hire Easthampton Indians, on account of their being already engaged by other companies, they ask relief in the premises,* which Governer Andross, in an order dated November 18, 1675, grants them, by allowing them to employ the aforesaid Shelter-Island Indians.† Another case is that of the widow of one Cooper, who in 1677 petitions Andross to compel some Indians who had been hired and paid their advance by her late husband to fulfill to her the contract made with him, they having been hiring out to other parties since his decease.‡ The trade in oil from Long Island early gravitated to Boston and Connecticut, and this was always a source of much uneasiness to the authorities at New York. The people inhabiting Easthampton, Southampton, and vicinity, settling under a patent with different guarantees from those allowed under the Duke of York, had little in sympathy with that government, and always turned toward Connecticut as their natural ally and Massachusetts as their foster mother. Scarcely had what they looked upon as the tyrannies of the New York governors reduced them to a sort of subjection when they were assailed by a fresh enemy. A sudden turn of the wheel of fortune brought them, in 1673, a second time under the control of the Dutch. During this interregnum, which lasted from July, 1673, to November, 1674, they were summoned, by their then * N. Y. Col. MSS., xxv, Sir Ed. Andross, p. 41. † Warrants, Orders, Passes, &c., 1674-1679, p. 161. ‡ N. Y. Col. MSS., xxvi, p. 153. |

conquerors, to send delegates to an assembly to be convened by the temporary rulers. In reply the inhabitants of Easthampton, Southampton, Southold, Seatoocook, and Huntington returned a memorial setting that up to 1664 they had lived quietly and prosperously under the government of Connecticut. Now, however, the Dutch had by force assumed control, and, understanding them to be well disposed, the people of those parts proffer a series of ten requests. The ninth is the particular one of interest in this connection, and is the only one not granted. In it they ask, "That there be ffree liberty granted ye 5 townes afresd for ye procuring from any of ye united Collonies (without molestation on either side:) warpes, irons or any other necessaries ffor ye comfortable carring on the whale design" To this reply is made that it "cannot in this conjunction of time be allowed." "Why," says Howell,* "the Council of Governor Colve chose thus to snub the English in these five towns in the matter of providing a few whale-irons and necessary tackle for capturing the whales that happened along the coast, is inconceivable;" but it must be remembered that the English and Dutch had long been rivals in this pursuit, even carrying their rivalry to the extreme of personal conflicts. The Dutch assumed to be, and practically were, the factors of Europe in this business at this period, and would naturally be slow to encourage any proficiency in whaling by people upon they probably realized that their lease of authority would be brief. Hence, although they were willing to grant them every other right in common with those of their own nationality, maritime jealousy made this one request impracticable. How the people of Long Island enjoyed this state of affairs is easy to infer from their petition of 1672. The oppressions alike of New York governors and Dutch conquerors could not fail to increase the alienation that difference of habits, associations, interests, and rights had implanted within them. Among other arbitrary laws was one compelling them to carry all the oil they desired to export to New York to be cleared, a measure which produced so much dissatisfaction and inconvenience that it was beyond a doubt "more honored in the breach than in the observance." At times some captain, more scrupulous than the rest, would obey the letter of the law or procure a remission of it. Thus, in April, 1678, Benjamin Alford, of Boston, in New England, merchant, petitioned Governor Brockholds for permission to clear with a considerable quantity of oil that he had bought at Southampton, directly from that port to London, he paying all duties required by law. This he desires to do in order to avoid the hazard of the voyage to New York and the extra danger of leakage thereby incurred. He was accordingly allowed to clear as he desired.† * Hist. of Southampton, p. 62. † N. Y. Col. MSS., xxvii, pp. 6i, 66. Accompanying the order is a blank clearance reading as follows: "Permitt & suffer the good ____ of ____ A. B. Commander, bound for the Port of London in Old England to passe from the Harbor at the North-Sea near Southton at the East End of Long Isl. with her loading of Whale Oyl & |

In 1684 an act for the "Encouragement of trade and Navigation" within the provinco of New York was passed, laying a duty of 10 per cent. on all oil and bone exported from New York to any other port or place except directly to England, Jamaica, Barbadoes, or some other of the Caribbean Islands. In May, 1688, the Duke of York instructs his agent, John Leven, to inquire into the number of whales killed during the past six years within the province of New York, the produce of oil and bone, and "about his share."* To this Leven makes reply that there has been no record kept, and that the oil and bone were shared by the companies killing the fish. To Leven's statement, Andross, who is in England defending his colonial government, asserts that all those whales that were driven ashore were killed and claimed by the whalers or Indians.† In August, 1688, we find the first record of an intention to obtain sperm oil. Among the records in the State archives at Boston is a petition from Timotheus Vanderuen, commander of the brigantine Happy Return, of New Yorke, to Governor Andross, praying for "Licence and Permission, with one Equipage Consisting in twelve mariners, twelve whalernen and six Diuers – from this Port, upon a fishing design about the Bohames Islands, And Cap florida, for sperma Coeti whales and Racks: And so to returne for this Port."‡ Whether this voyage was ever undertaken or not we have no means of knowing, but the petition is conclusive evidence that there were men in the country familiar even then with some of the haunts of the sperm whale and with his capture. Francis Nicholson, writing from Fort James, December, 1688, says: "Our whalers have had pretty good luck, killing about Graves End three large whales. On the Easte End aboute five or six small ones."§ During this same year the town of Easthampton being short of money, debtors were compelled to pay their obligations in produce, and in order to have some system of exchange the trustees of the town "being Legally met March 6, 1688-9 it was agreed that this year's Towne rate should be held to be good pay if it be paid as Follows:

Whalebone without any manner of Lett Hindrance or Molestation, shee having hectic cleared by order from the Custom house here & given security accordingly. Given under my hand in N. Y. this 20th day of April in the 30th yeare of his Maties raigne Ao Domini 1678. "To all his Maties Officrs whom this way Concerne." * N. Y. Col. Records, iii, p. 282. † Ibid., p. 311. ‡ Mass. Col. MSS., Usurpation, vi, p. 126. § Ibid., iv, p. 303. ¡ Bi-Centennial Address at Easthampton, p. 41. |

The first whaling expedition in Nantucket "was undertaken," says Macy,* "by some of the original purchasers of the island; the circumstances of which are handed down by tradition, and are as follows: A whale, of the kind called 'scragg,' came into the harbor and continued there three days. This excited the curiosity of the people, and led them to devise measures to prevent his return out of the harbor. They accordingly invented and caused to be wrought for them a harpoon, with which they attacked and killed the whale. This first success encouraged them to undertake whaling as a permanent business; whales being at that time numerous in the vicinity of the shores" In 1672 the islanders, evidently desirous of making further progress in this pursuit, recorded a memorandum of a proposed agreement with one James Loper, in which it is said that the said James >"doth Ingage to carrey on a Designe of Whale Catching on the Island of Nantucket that is to say James Ingages to be a third in all Respects, and som of the Town Ingages also to carrey on the other two thirds with him in like manner – the town doth also consent that first one company shall begin, and afterwards the rest of the freeholders or any of them have Liberty to set up another Company provided they make a tender to those freeholders that have no share in the first company and if any refuse the rest may go on themselves, and the town doth engage that no other Company shall be allowed hereafter; also, whoever kill any whales, of the Company or Companies aforesaid, they are to pay to the Town for every such whale five shillings and for the Incoragement of the said James Loper the Town doth grant him ten acres of Land in sume Convenant place that lie may chuse in (Wood Land Except) and also liberty for the commonage of three cows and Twenty sheep and one horse with necessary wood and water for his use, on Conditions that he follow the trade of whalling on this Island two years in all seasons thereof beginning the first of March next Insuing; also he is to build upon his Land and when he leaves Inhabiting upon this Island then he is first to offer his Land to the Town at a valuable price and if the Town do not buy it he may sell it to whom he please; the commonage is granted only for the time of his staying here."† At the same meeting John Savidge had a * Hist. Nantucket, p. 28. † There are most excellent reasons for concluding that Loper never went to Nantucket. When the parties to whom grants were made settled there, their lots were surveyed and laid out to them and the survey recorded. In Loper's case no after-mention occurs of him in any place or manner, and in the list of proprietors and their grants, made np in 1674, and forwarded to New York, his name is not mentioned. Notwithstanding the islanders, in, their desire to honor and perpetuate his name, called two of their ships after him, those who are best judges in the matter concede that be never had a residence there. One James Loper (or Looper) resided at Easthampton and carried on whaling from there prior to 1675 (see petition of Shallenger, Hand & Loper). Undoubtedly this is the man referred to in the Nantucket records. Up to the year 1678, however, be still owned property in Easthampton. In regard to the Loper mentioned by Felt (Annals of Salem, p. 223), and who has been supposed (see Savage's |

grant made to him, upon condition that lie took up his residence on the island for the space of three years, and also that he should "follow his trade of a cooper upon the island as the Town or whale Company have need to employ him." Loper beyond a doubt never improved this opportunity offered him of immortalizing himself, but Savidge did, and a perverse world has, against his own will, banded down to posterity the name of Loper, who did not come, while it has rather ignored that of Savidge, who did remove to that island. The history of whaling upon Nantucket from that time until 1690 is rather obscure. There is a tradition among the islanders that in this year several persons were standing upon what was afterward known as Folly House Hill, observing the whales spouting and sporting in the sea. One of these people, pointing to the ocean, said to the others: "There is a green pasture, where our children's grandchildren will go for bread."* It would be a matter of interest to know the name of the individual to whom this prophetic vision was revealed, but tradition is almost always lame somewhere. In 1690 the people of Nantucket, "finding that the people of Cape Cod had made greater proficiency in the art of whale-catching than themselves," sent thither and employed Ichabod Paddock to remove to the island and instruct them in the best method of killing whales and obtaining the oil.† Judging from subsequent events, he must have come and proved himself a good teacher and they most admirable pupils. The earliest mention of whales at Martha's Vineyard occurs in November, 1652, when Thomas Daggett and William Weeks were appointed "whale cutters for this year." The ensuing April it was "Ordered by the town that the whale is to be cut out freely, four men at one time, and four at another, and so every whale, beginning at the east end of the town." In 1690 Mr.‡ Sarson and William Vinson were appointed by "the proprietors of the whale" to oversee the cutting and sharing of all whales cast on shore within the bounds of Edgartown, "they to have as much for their care as one cutter." genealogical dictionary) to be the one spoken of, the petition (Mass. Col. MSS., Usurpation, ii, p. 136) gives his name as Jacobus Loper, and it is by this name alone be is known. Thus in 1686 the constable of Eastbam was ordered to attach Jacobus Loper to find sureties for good behavior and appearance at the next court, and at the October term Jacobus Loper was acquitted of a criminal charge. In no place does the Latin name undergo a change, and accompanying circumstances would scarcely seem to imply that the appellation was ever intended to be James. On the contrary the Nantucket document plainly says James, as also do the MSS. relating to Easthampton, and in no place is the Latinized form used. * Macy's Nantucket, p. 33. † Macy's Nantucket, pp. 29-30. No record exists of this save in the form of tradition, but many circumstances give it an appearance of far greater probability than the story concerning Loper. Among other things, it is related as an historical fact by Zaccheus Macy (Mass. Hist. Soc., Col. iii, p. 155), who died in 1797, aged 83 years, and hence was cotemporary with some of the men living in Paddock's time. He, however, makes no mention of Loper. ‡ Richard L. Pease, esq., in Vineyard Gazette. |

In 1692 came the inevitable dispute of proprietorship. A whale was cast on shore at Edgartown by the proprietors, "seized by Benjamin Smith and Mr. Joseph Norton in their behalf," which was also claimed by "John Steel, harpooner, on a whale design, as being killed by him." It was settled by placing the whale in the custody of Richard Sarson, esq., and Mr. Benjamin Smith, as agents of the proprietors, to save by trying out and securing the oil; "and that no distribution be made of the said whale, or effects, till after fifteen days are expired after the date hereof, that so such persons who may pretend an interest or claim, in the whale, may make their challenge; and in case such challenge appear sufficient to them, then they may deliver the said whale or oyl to the challenger; otherwise to give notice to the proprietors, who may do as the matter may require." Mr. Felt, in his History of Salem,* says that James Loper, of that town, in 1688, petitioned the colonial government of Massachusetts for a patent for making oil. In his petition Loper represents that he has been engaged in whale-fishing for twenty-two years. On the 12th of March, 1692, John Higginson and Timothy Lindall, of Salem, wrote to Nathaniel Thomas: "We have been jointly concerned in severall whale voyages at Cape Cod, and have sustained greate wrong and injury by the unjust dealing of the inhabitants of those parts, especially in two instances: ye first was when Woodbury and company, in our boates, in the winter of 1690, killed a large whale in Cape Cod harbour. She sank and after rose, went to sea with a harpoon, warp, etc. of ours, which have been in the hands of Nicholas Eldredge. The second case is this last winter, 169t. William Edds and company, in one of our boates, struck a whale, which came ashore dead, and by ye evidence of the people of Cape Cod was the very whale they killed. The whale was taken away by Thomas Smith, of Eastham, and unjustly detained."† Nor was the art of whaling unknown or unpracticed by our Canadian neighbors in these early years, for M. de Denonville writes to M. de Seignelay, in 1690, that the Canadians are adroit in whaling, and that the "last ships have brought to Quebec, from Bayonne, some harpooners for Sieur Riverin."‡ * Vol. ii, p. 224. † Ibid. ‡ Memoir on Acadia, &c., N. Y. Col. Rec., ix, pp. 444-5. Holmes, in his "American Annals" (vol. i, p. 133), says: "Other English ships went this year (1593) to Cape Breton. This is the first mention, that we find, of the whale-fishery by the English. Although they found no whales in this instance, yet they discovered on an island eight hundred whale fins where a Biscay ship bad been three years before; and this is the first account we have of whale fins or whale bone by the English." So it appears that for a long term of years Canadian waters were the whaleman's garden. |

C. – 1700 TO 1750. |

encouragement they soon became experienced whalemen and conversant with all the details of the business.* The first sperm whale taken by Nantucket whalemen was captured by Christopher Hussey, about the year 1712, and the capture, destined to effect a radical change in the pursuit of this business, was the result of an accident. "He was cruising," says Macy,† "near the shore for Right whales, and was blown off some distance from the land by a strong northerly wind, where he fell in with a school of that species of whales, and killed one and brought it home. * * * * This event gave new life to the business, for they immediately began with vessels of about thirty tons to whale out in the 'deep,' as it was then called, to distinguish it from shore whaling. They fitted out for cruises of about six weeks, carried a few hogsheads, enough probably to contain the blubber of one whale, with which, after obtaining it, they returned home. The owners then took charge of the blubber, and tried out the oil, and immediately sent the vessels out again."‡ In 1715 Nantucket had six sloops engaged in this fishery, producing oil to the value of £1,100 sterling, the shore fishery being, in the mean time, still continued. There was no perceptible diminution in the number of whales taken from along the coast for quite a number of years after the establishment of the fishery. In 1720 the inhabitants of Nantucket made a small shipment of oil to London in the ship Hanover, of Boston, William Chadder, master.§ * Macy's Hist., p. 30. † Ibid., p. 36. ‡ The first sperm whale known to Nantucket "was found dead, and ashore, on the southwest part of the island. It caused considerable excitement, some demanding a part of the prize under one pretence, some under another, and all were anxious to behold so strange an animal. There were so many claimants of the prize, that it was difficult to determine to whom it should belong. The natives claimed the whale because they found it" (not a bad reason surely); "the whites, to whom the natives made known their discovery, claimed it by a light comprehended, as they affirmed, in the purchase of the island." (Ah! what lawyers they must have been!) "An officer of the crown" (here steps in the lion) "made his claim, and pretended to seize the fish in the name of His Majesty, as being property without any particular owner. " * * * It was finally settled that the white inhabitants who first found the whale, should share the prize equally amongst themselves." (Alas for royalty, and alas for the finders!). The teeth, considered very valuable, bad been prudently taken care of by a white man and an Indian before the discovery was made public. The decision iu regard to ownership certainly justified their precaution. This compromise made, the whale was cut up and the oil extracted. What the amount of it was is unknown. "The sperm procured from the head was thought to be of great value for medical purpose.s It was used both as an internal and an external application; and such was the credulity of the people, that they considered it a certain cure for all diseases; it was sought with avidity, and, for a while, was esteemed to be worth its weight in silver."-(Macy's Hist.) § [N. S.] "Shipped by the grace of God, in good order and well conditioned, by Paul Starbuck, in the good ship called the Hanover, whereof is master under God for thepresent voyage, William Chadder and now riding in the harbour of Boston, and by God's grace bound for London; to say: – six barrels of |

Whether this was the first adventure of this kind or not we have no means of ascertaining, and we are in a similar state of uncertainty in regard to its success. As the fishery became more important, and vessels were used, it became necessary to select the site where there was the best harbor, and the location where the town of Nantucket now stands was selected.* As the number of vessels increased it was also found necessary to replace the old landing-places, which at best were only temporary, and often destroyed by winter storms, with more subtantial wharves, and accordingly, in 1723, the "Straight" wharf was built.† At this time the usual custom in winter was to haul the vessels and boats up on shore, as being safer and less expensive than lying at the wharf. The boats were placed bottom upwards and lashed together to prevent accidents in gales of wind, and the whaling "craft" was carefully stored in the warehouses. In the early days of whaling each vessel carried two boats, one of which seems to have been held in reserve in case of accident to the one lowered for whales. In 1730 Nantucket employed in the fishery twenty-five vessels of from traine oyle, being on the proper account & risque of Nathaniel Starbuck, of Nantucket, and goes consigned to Richard Patridge merchant in London. [Prin. Paid.] Being marked & numbered as in the margin & to be delivered in like good order & well conditioned at the aforesaid port of London (The dangers of the sea only excepted) unto Richard Partridge aforesaid or to his assignees, He or they paying Freight for said goods, at the rate of fifty shillings per tonn, with primage & average accustomed. "In witness whereof the said Master or Purser of said Ship bath affirmed to Two Bills of Lading all of this Tener and date, one of which two Bills being Accomplished, the other to stand void. "And so God send the Good Ship to her desired Port in safety. Amen! "Articles & contents unknown to "(Signed) WILLIAM CHADDER. "Dated at Boston the 7th 4th me. 1720." (From original bill of lading in possession of F. C. Sanford, esq.) * The place first settled was at Maddeket, at the west end of the island. According to the records in the state-house at Boston, the following vessels were registered as belonging to Nantucket up to the year 1714: April 28, 1698, Richard Gardner, trader, registers sloop Mary, 25 tons, built in Boston, 1694; August 11, James Coffin, trader, registers sloop Dolphin, 25 tons, built in Boston, 1697; September 1, Richard Gardner, mariner, registers sloop Society, 15 tons, built in Salem, 1695; April 4, 1710, Peter Coffin, registers sloop Hope, 40 tons, built in Boston, 1709; April 24, 1711, Silvanus Hussey, sloop Eagle, 30 tons, built at Scituate, 1711; July 30, 1713, Silvanus Hussey, sloop Bristol, 14 tons, built at Tiverton, 1711; April 27, 1713, Abigail Howse, sloop Thomas, 12 tons, built at Newport, R. I., 1713; May 4, 1714, Ebenezer Coffin, sloop Nonsuch, 25 tons, built at Boston, 1714. (The Nonsuch is registered as of Boston; Coffin, however, was of Nantucket); 1714, Geo. Coffin, sloop Speedwell, 25 tons, built at Charlestown. This, then, was the character of their vessels up to 1715; among them the Hope, of 40 tons, was a very giant. In 1732, however, the size had very greatly increased, for by a petition (Mass. Col. MSS. Maritime, v, p. 510), it appears that Isaac Myrick built at Nantucket a snow of 118 tons. † Macy's Hist., p. 37. According to the Boston News Letter, European advicos of August 3, 1724, reported that the Emperor of Russia bad ordered the directors of the India Company 11 newly erected there" to get twelve vessels ready against the opening |

38 to 50 tons burden each, and the returns were about 3,700 barrels of oil, worth, at £7 per ten, £3,200. Holmes says:* "The whale-fishery on the North American coasts must, at this time" (1730), "have been very considerable; for there arrived in England from these coasts, about the month of July, 151 tons of train and whale oil, and 9,200 of whale bone." At this time there were nearly five hundred ships, manned by four thousand sailors, engaged in foreign traffic from Massachusetts.† The culminating point of shore-whaling at Nantucket was probably reached in 1726. During that year there were 86 whales taken by boats, and the Coffins and Gardners, the Folgers, the Husseys, the Swains and Paddacks, the progenitors of that race of men who carried the name and fame of the little island of Nantucket to every accessible port on the globe, are chief among those who gathered this harvest.‡ The first recorded loss of a whaling-vessel from the island occurred in 1724, when a sloop, of which Elisha Coffin was master, was lost at sea with all on board.§ The second loss was that of another sloop, Thomas of the spring, to sail for the Greenland whaling-ground, promising to them both protection and monopoly, "by which it will be prohibited, under severe penalties, to bring for the future any Oil or Whalebone into any Part of His Majesty's Dominions from Foreign Countries." Early in 1725 the directors of the English South Sea Company ordered 12 more ships for whaling in these seas. (The inference is that as early at least as the previous year, 1724, the company had vessels there.) Under date of London, July 24, 1725, the ships are reported all returned. The English ships took 25 whales, producing 1,000 puncheons of blubber and oil and 26 tons of fins, worth £450 per ton. In the Dutch fishery, the Hollanders, with 144 ships took 240 whales; the Hamburgbers with 43 ships took 463 whales; the Bremenese with 23 ships took 29 whales; the Bergenese with 2 ships took none, and two other ships returned empty. In the spring of 1726, Sweden also looked with longing eyes upon this pursuit, and designed sending twelve ships in the summer of that year to Greenland. * American Annals, i, p. 126. † Ibid. ‡ The names of the parties (probably captains of boats or vessels), with the number of whales taken by each, may be of interest in this connection: John Swain took 4, Andrew Gardner 4, Jonathan Coffin 4, Paul Paddack 4, Jas. Johnston 5, Clothier Pierce 3, Sylvanus Hussey 2, Nathan Coffin 4, Peter Gardner 4, Wm. Gardner 2, Abisbai Folger 6, Nathan Folger 4, John Bunker 1, Shaubael Folger 5, Shubael Coffin 3, Nath'l Allen 3, Edw'd Heath 4, Geo. Hussey 3, Benj. Gardner 3, Geo. Coffin 1, Rich'd Coffin 1, Nath'l Paddack 2, Jos. Gardner 1, Matthew Jenkins 3, Bartlett Coffin 4, Daniel Gould 1, Ebenezer Gardner 4, ______ Staples 1; total 86. The largest number of whales taken in one day was eleven. In the New England Weekly Journal of December 21,1730, appears an advertisement, informing the public that there has been "Just Reprinted, The Wonderful Providence of God, Exemplified in the Preservation of William Walling who was drove out to Sea from Sandy Hook near New York in a leaky Boat, and was taken up by a Whaling Sloop & brought to Nantucket after he bad floated on the Sea eight Days without Victuals or Drink." In 1732, according to a petition in the Mass. Col. MSS. (Maritime, iv, p. 510), a vessel of 118 tons burden was built at Nantucket, the ruling price being then £8 5s. per ton. § Zaccheus Macy, in a brief sketch of Nantucket, published in val. iii of the Mass. Hist. Soc.'s Coll., says (p. 157) that up to 1760 no man had been killed or drowned while whaling, and this error Obed Macy, in his History of Nantucket, perpetuates. It must have been intended by the former to include only shore-whaling, since prior to the |

Hathaway master, in 1731. These losses were a serious matter for a small whaling-port, where nearly all the inhabitants were related by birth or marriage. In the year 1742 still another sloop, commanded by Daniel Paddack, was lost while on a whaling-voyage, with all on board. An increase in the business brought with it an increase in the number and size of the vessels employed. Schooners were added, and the size of the vessels increased to between 40 and 50 tons. Whales began to grow scarce in the vicinity of the shore, and still larger vessels were put into the service and sent to the "southward" as it was termed, cruising on that ground till about the first of July, when they returned, refitted, and cruised to the eastward of the Grand Bank during the remainder of the whaling season, unless, as was often the case, they filled sooner. Vessels for this service were generally "sloops of 60 or 70 tons; their crews were made up, in part, of Indians,"* there being generally from four to eight natives to each vessel. But the time came when Nantucket did not furnish men enough to man the whaling-vessels which the islanders desired to fit out, and Cape Cod, and even Long Island, were called in to supply the deficiency of seamen. It naturally occurred that, with the limited colonial demand, the business became at times overdone, the market glutted, and what oil was sold was disposed of at too low a price to be as remunerative as the islanders thought it should be. The people began to think of another market. For a series of years they had made Boston their factor, selling there their oil and drawing from thence their supplies.† Probably period named at least nine vessels with their crews had been lost, and these facts must have been well known Whim. There is on file at the State-house in Boston (Domestic Relations, vol. 1, p. 181), a petition to the general court from Dinah Coffin, of Nantucket, setting forth that "her Husband, Elisha Coffin did on the Twenty `evcnth Day of April Annoq Dom: 1722 Sail from sd Island of Nantucket in a sloop: on a whaling trip intending to return in a month or six weeks at most, And Instantly a hard & dismall Storm followed; which in all probability Swallowed him and those with him up: for they were never heard of." She prays that she may now (1724) be allowed to marry again. * Zaccheus Macy writes (Mass. Hist. Soc. Coll., iii, p. 157), "It happened once, when there were about thirty boats about six miles from the shore, that the wind came round to the northward, and blew with great violence, attended with snow. The men all rowed hard, but made but little headway. In one of the boats were four Indians and two white men. An old Indian in the head of the boat, perceiving that the crew began to be disheartened, spake out load in his own tongue and said, "Momadich-chator auqua sarshkee sarnkee pinchee eynoo sememoochkee chaquanks wihchee pinches eynoo;' which in English is, 'Pull ahead with courage; do not be disheartened; we shall not be lost now; there are too many Englishmen to be lost now.' His speaking in this manner gave the crew new courage. They soon perceived that they made headway; and after long rowing they all got safe on shore." In 1744 a Nantucket Indian struck a blackfish, and was caught by a foul line and carried down and drowned. – (Boston News-Letter.) † It would be inferred that the shipment made in 1720 did not prove entirely satisfactory. The Boston News-Letter reports that Captain Churchman arrived at Portsmouth, Eng., December 8, 1729, from New England for London, with a cargo of log-wood and oil. |

had their oil commanded the price which they considered it should have brought, this state of affairs might long have continued, but such was not the case. "It was found," says Macy,* "that Nantucket had in many places become famed for whaling, and particularly so in England, where partial supplies of oil had been received through the medium of the Boston trade. The people, finding that merchants in Boston were making a good profit by first purchasing oil at Nantucket, then ordering it to Boston, and thence shipping it to London, determined to secure the advantages of the trade to themselves, by exporting their oil in their own vessels. They had good prospects of success in this undertaking, yet, it being a new one, they moved with great caution, for they knew that a small disappointment would lead to embarrassments that would, in the end, prove distressing. They, therefore, loaded and sent out one vessel, about the year 1745. The result of this small beginning proved profitable, and encouraged them to increase their shipments by sending out other vessels. They found, in addition to the profits on the sales, that the articles in return were such as their business required, viz, iron, hardware, hemp, sailcloth, and many other goods, and at a much cheaper rate than they had hitherto been subjected to." This naturally gave renewed life to the enterprise, and induced the fitting of new vessels and the development of new adventurers. The sky was not always fair, not every voyage proved remunerative, but the business as a whole steadily increased in importance and profit. At about this time (1746), according to Macy's History, whaling was commenced by our people in Davis's Straits.† The transfer of the trade of Long Island to Boston and Connecticut was a source of great uneasiness to the early governors of New York. They were repeatedly stirred up on the subject by the lords of trade in England, but with all their trouble and skill and efforts they were unable to alienate the sympathies of the Long Islanders from those who were their friends both by birth and association. They had but little in common with the New York government, which seemed to them only the symbol of wrong, injustice, and oppression. The governors of that * Page 51. The Boston News-Letter of October 5, 1738, reports from Nantucket that an Indian plot to fire the English houses and kill the inhabitants of the island, had been disclosed by a friendly Indian. In consequence of the warning the plot had been abandoned, but fears were entertained for the safety of several whaling-vessels which sailed in the spring, and of the crews, of which the natives formed an essential part. † Page 54. Davis's Straits were visited by whalemen as early as 1732, when a Captain Atkins, returning from a whaling voyage thence, brought a Greenland bear. Captain Atkins went as far as 66° north. Among the entries and clearances at the Boston custom-house as recorded in the Boston News-Letter as early as 1737 we find several to and from this locality. Beyond a doubt these vessels are whalemen, and in fact some of the names are common in the annals of this industry at Nantucket. The clearances were usually in March or April, and the arrivals from September to November, varying according to the degree of success, the season, &c. In July, 1737, Capt. Atherton Hough took a whale f° in the Straits," and in 1739, Under date of August 2, the Boston News-Letter says: "There is good Prospect of Success in the Whale Fishery to Greenland |

province were numerous and tyrannical, and the people had no redress. The boast of one of them that be would tax them so high that they would have no time to think of anything else but paying these duties, seemed to be resolved into a motto adopted by the majority, and the groanings and writhings of the people only seemed to serve as the excuse for another turn of the screws of executive tyranny. In June, 1703, Lord Conbury, in a letter to the lords of trade,* speaking of the difficulties the commerce of New York had to contend with from the position of some parts of its territory in relation to Connecticut and Massachusetts, writes that Connecticut fills that part of Long Island with European goods cheaper than New York can, since New York pays a duty which is not assessed by Connecticut; "nor will they" (the inhabitants of the east end of Long Island) "be subject to the Laws of Trade nor to the Acts of Navigation, by which means there has for some time been no Trade between the City of New Yorke and the East end of Long Island, from whence the greater quantity of Whale oyle comes." He adds that the people are full of New England principles, and would rather trade with Boston, Connecticut, and Rhode Island than with New York. In 1708, however, under Lord Cornbury, an act was passed for the "Encouragement of Whaling," in which it was provided, 1st, that any Indian, who was bound to go to sea whale-fishing, should not "at any time or times between the First Day of November and the Fifteenth Day of April following, yearly, be sued arrested, molested, detained or kept out of that Imployment by any person or persons whatsoever, pretending any Contract, Bargain Debt or Dues unto him or them except and only for or concerning any Contract, Debt or Bargain relating to the Undertaking and Design of the Whale-fishing and not otherwise under the penalty of paying treble Costs to the Master of any such Indian or Indians so to be sued, arrested, molested or detained." Section 2 provided that "if any person or persons shall purchase, take to pawn or anyways get or receive any Cloathing, Gun or other Necessaries that his Master shall let him, from any such Indian or Indians or suffer any such Indian to be drinking or drunk in or about their Houses, when they should be at Sea, or other business belonging to that this Year, for several vessels are come in already, deeply laden, and others expected." This is not mentioned as by any means an extraordinary circumstance, and when it is remembered that the English had already pursued the whale in those seas for fifteen years, and at that time had some forty or fifty ships tbore engaged in this pursuit, it would scarcely be likely to excite surprise. In 1744, a whale 40 feet long was found ashore on Nantucket, by three men, who, for lack of more proper instruments, killed it with their jack-knives. (News-Letter October 4.) * N. Y. Col. Rec. iv, p. 1058. An order was passed in the New York Council, March 2,1702, directing Thomas Clark and John Crosier, of Suffolk County, to secure three drift whales ashore in said county, they to have one-third of the oil and bone and to deliver the remaining two-thirds to the New York custom-house clear of charge. (Council Minutes, viii, p. 323.) |