He eventually returned to Paris due to ill-health – probably syphilis – and in 1842, after dining with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Stendhal collapsed in the street and died soon after. His self-composed epitaph was: 'He lived, He wrote, He loved.

23 FEBRUARY 2012

MAIN POSTS / READING / POLITICS

‘Love is a madness most discreet’: The Red and the Black, A Chronicle of 1830 by Stendhal

Jane Gleeson-White

Stendhal’s dazzling, fast-paced The Red and the Black: A Chronicle of 1830is one of my all-time favourite novels. It’s written with an urgency that’s still palpable, almost 200 years on.

Stendhal’s dazzling, fast-paced The Red and the Black: A Chronicle of 1830is one of my all-time favourite novels. It’s written with an urgency that’s still palpable, almost 200 years on.The Red and the Black was published in France in 1830, some 15 years after the fall from power of Napoleon Bonaparte, Stendhal’s lifelong hero. The novel is a fierce attack on France following Napoleon’s demise, the story of a young man determined to find heroism in those vacuous days, and a lament for heroic times gone by:

‘Since the fall of Napoleon, any appearance of gallantry has been strictly banned from provincial mores … Boredom has become acute. The only pleasures are reading and agriculture.’

The hero of The Red and the Black, Julien Sorel, is a young man with a ‘mad passion for Bonaparte’. Inspired by Napoleon, Julien dreams of rising to the glorious heights of French society from his meagre peasant origins. Handsome, proud and overly sensitive, driven by passion and ambition like Napoleon, Julien is convinced a great destiny awaits him. Unlike his older brothers who work in their father’s sawmill, Julien learns to read and write. His prodigious memory and astonishing ability to quote entire passages from the New Testament in Latin secure him his first job, as tutor to the sons of the Mayor of Verrieres, an imaginary town in the foothills of the Jura Mountains where Julien grows up.

Julien soon realises that in post-Napoleonic France the surest path to success for a poor peasant boy is the priesthood, just as the military had been in Napoleon’s day: ‘All right then! he said to himself, laughing like Mephistopheles, I’ve got more intelligence than they have; I can pick the right uniform for my century. And he felt a resurgence of ambition and attachment for the robes of the priesthood.’

But the Church and its uniform are not the only weapons in Julien’s arsenal for his assault on society. He uses another equally potent one: seduction. While struggling with the demands of the priesthood, including the hypocrisy it requires, Julien plans to advance by seducing beautiful, powerful women. Just as his heroes use their intelligence, looks, passion and energy as weapons, Julien intends to do the same.

Stendhal based The Red and the Black on two contemporary court cases he read about in one of his favourite journals, which recorded daily court proceedings. The journal’s extraordinary tales of extreme crimes of passion among ordinary people convinced Stendhal that the energy, passion and imagination required for the future of France lay not in the hands of aristocrats and the bourgeoisie but in those of the workers and peasants like Julien Sorel.

At every turn on Julien’s faltering path to success, he chooses imagination over bland materialism. ‘Like Hercules he found himself with a choice – not between vice and virtue, but between the unrelieved mediocrity of guaranteed well-being, and all the heroic dreams of his youth.’ At the same time, however, Julien wonders if he has what it takes for success, worries that his need to earn a living will exhaust him before he’s achieved glory: ‘I’m not made of the stuff of great men, since I’m afraid that eight years spent earning my living may drain me of the sublime energy which gets extraordinary feats accomplished.’

As well as being a sensitive portrayal of a new kind of hero, The Red and the Black is a brilliant satirical portrait of French society. Stendhal writes fiercely of his contemporary world, the post-Napoleonic reign of the reactionary Charles X. Stendhal lived in Paris from November 1821 to November 1830, and his novel is based on first-hand experience of the corruption, hypocrisy and self-interest that prevailed. In a scene that could come from Yes, Prime Minister, the counter-revolutionary French aristocrats plot the invasion of their own nation, France:

‘Foreign kings will only listen to you when you announce the presence of twenty thousand gentlemen ready to take up arms to open the gates of France to them. Guaranteeing this support is a burden, you’ll tell me; gentlemen, our heads remain on our shoulders at this price.’

Stendhal’s social commentary is astute. He understands the power of the priesthood and perhaps too the dawning power of the press: ‘Yet men like this [priests] are the only moral teachers available to the common people, and how would the latter fare without them? Will newspapers succeed in replacing priests?’ He also diagnoses the symptom of the increasingly influential new class, the bourgeoisie, which will so nauseate Flaubert: ‘BRINGING IN MONEY: this is the key phrase which settles everything in Verrieres.’

Balzac commented that Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma (1839) ‘often contains a whole book in a single page’, and so it is with The Red and the Black. Stendhal writes with such urgency, cramming his pages with such remarkable, breathtakingly unexpected events, that his novel encompasses the length and breadth of a whole society. His chatty narrator often breaks from the story to engage directly with the reader, discussing current fashions, politics, mores and modes of thought, which gives the novel a topical immediacy that was unheard of in Stendhal’s day:

‘in Paris, love is born of fiction. The young tutor and his shy mistress would have found three or four novels, and even couplets from the Theatre de Madame, clarifying their situation. The novels would have outlined for them the roles they had to play, and given them a model to imitate.’

Stendhal was born Marie-Henri Beyle in Grenoble in 1783. His beloved mother died when he was seven and he was left in the care of his domineering father, a barrister in Grenoble’s high court of justice. As soon as he could, Stendhal left Grenoble for Paris to seek his fortune and escape his father, whom he resented.

Stendhal arrived in Paris at a fateful moment: in 1799, the day after Napoleon Bonaparte took power with the coup d’etat of 18 Brumaire. Napoleon was to be the shaping force not only of the age but of Stendhal’s life and novels. Stendhal had shown an interest in literature and mathematics, and his father expected him to go to Paris’s Ecole Polytechnique. Instead, Stendhal was taken up by his father’s cousin Noel Daru and his sons Pierre and Martial, powerful members of Napoleon’s bureaucracy. Pierre and Martial educated their provincial relative in the ways of a Parisian dandy and found him a position as a clerk in Napoleon’s Ministry of War. When Napoleon decided to attack the Austrians in Italy, Stendhal was offered a commission and travelled through the Alps to join Napoleon’s army. There he discovered the pleasures of Italian culture, especially in Milan, and the hardships of military life. His dreams of a noble military career were dashed by the coarseness of soldiers and in 1802, aged 19, Stendhal returned to Paris and began to write.

In Paris Stendhal was given one of the top government positions in the empire and mixed with the cream of Parisian society, including Napoleon’s sisters, Mme de Stael, Mme Recamier, Prince Metternich and the painter Jacques-Louis David. He even had an audience with the empress, Marie-Louise, before joining Napoleon’s army on its invasion of Russia, where he witnessed the burning of Moscow.

When Napoleon was defeated in 1814, Stendhal could not bring himself to live in Restoration France, so he settled in Milan. Here he published his first books on art, music and travel, under the pseudonym ‘Alexandre Cesar Bombet’. In the climate of fear and opportunism in France at the time, spies and counterfeit activities were rife. Beyle himself adopted about 200 different names, including ‘William Crocodile’, and finally settled with ‘Stendhal’ for his novels, a name that he’d used for the first time in 1817 when he published his first travel book Rome, Naples and Florence in 1817. Stendhal, who never married, had many affairs and fell madly in love with Metilde Dembowski in Milan in 1818. His unrequited passion for her haunted him for the rest of his life.

Stendhal left Milan in 1821 and returned to Paris, where his sharp intellect and original wit were much celebrated in the salons. His first novel, Armance, was published in 1827. Three years later, aged 47, he published The Red and the Black, dedicated ‘To the Happy Few’. The ‘happy few’ were the small group of people who espoused the view of life Stendhal named ‘beylism’, those who believed in the value of passion, energy and originality, who constantly questioned the customs and codes of the day while appearing to conform to them, in order to be happy.

Following the July Revolution of 1830 and the ascendancy of ‘the bourgeois monarch’ Louis-Philippe, Stendhal was appointed French consul in the port of Civitavecchia in the Papal States. He eventually returned to Paris due to ill-health – probably syphilis – and in 1842, after dining with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Stendhal collapsed in the street and died soon after. His self-composed epitaph was: ‘He lived, He wrote, He loved.’

Stendhal predicted that his work would not be appreciated for another fifty years. His novels, with their penetrating, ironic portraits of contemporary society, were shocking in his day and his genius was not widely appreciated until after his death. Many later writers of the 19th and 20th centuries were influenced by his vision, including Nietzsche, Proust and Camus. In his novel Vertigo (published in English in 1999), the German writer WG Sebald draws on Beyle’s recollections of his youthful military adventures in Napoleon’s army. The opening section of the novel is called ‘Beyle, or Love is a Madness Most Discreet’.

The widely documented ‘Stendhal syndrome’ is named after Stendhal’s ecstatic, hallucinatory response to the frescoes in a chapel of the church of Santa Croce in Florence, about which he wrote: ‘Absorbed in the contemplation of sublime beauty … I reached the point where one encounters celestial sensations … Everything spoke so vividly to my soul.’ From the early 19th century on there have been many stories of people fainting before the beautiful art of Florence, but the syndrome was only named in 1979 by Italian psychiatrist Dr Graziella Magherini (at the time, chief of psychiatry at Florence’s Santa Maria Nuova Hospital), who saw over 100 cases of the syndrome, ranging from panic attacks to cases of madness that lasted days.

Cross-posted from bookish girl.

Overland is a not-for-profit magazine with a proud history of supporting writers, and publishing ideas and voices often excluded from other places.

If you like this piece, or support Overland’s work in general, please subscribe or donate.

RELATED ARTICLES & ESSAYS

24 FEBRUARY 2023

MAIN POSTS

Final Results of the 2022 Judith Wright Poetry Prize

Editorial Team

Overland, the judges and the Malcolm Robertson Foundation are thrilled to announce the final results of the 2022 Judith Wright Poetry Prize.

24 FEBRUARY 2023

MAIN POSTS

Final Results of the 2022 Neilma Sidney Short Story Prize

Editorial Team

Overland, the judges and the Malcolm Robertson Foundation are thrilled to announce the final results of the 2022 Neilma Sidney Short Story Prize.

CONTRIBUTE TO THE CONVERSATION

Ben Eltham says:

23 February 2012 at 10.53 am

I love this novel so much

REPLY

Clare says:

23 February 2012 at 12.04 pm

“I can pick the right uniform for my century.” Gotta love a man who knows the power of costume. Such a good read, thanks Jane.

REPLY

Dennis Garvey says:

23 February 2012 at 7.42 pm

Bourgeois to the Hilton, but yep, one my all time favourites too. Oh happy days…

REPLY

Jane GW says:

28 February 2012 at 6.13 pm

Yes Clare I love the whole costume for the century thing too. It must have been the suit – or the lab coat – for the 20th century, and I’m going for a green dress for the 21st.

And sorry for neglecting all accents on French words above, my symbols gadget wouldn’t add them.

REPLY

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

COMMENT *

Name

Website

The Red and the Black

Henri Dubouchet's illustration for an 1884 edition of Le Rouge et le Noir, Paris: L. Conquet | |

| Author | Stendhal (Henri Beyle) |

|---|---|

| Original title | Le Rouge et le Noir |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Bildungsroman |

| Publisher | A. Levasseur |

Publication date | November 1830 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 2 vol. |

| ISBN | 0-521-34982-6 (published before the ISBN system) |

| OCLC | 18684539 |

| 843/.7 19 | |

| LC Class | PQ2435.R72 H35 1989 |

Original text | Le Rouge et le Noir at French Wikisource |

| Translation | The Red and the Black at Wikisource |

Le Rouge et le Noir (French pronunciation: [lə ʁuʒ e l(ə) nwaʁ]; meaning The Red and the Black) is a historical psychological novel in two volumes by Stendhal, published in 1830.[1] It chronicles the attempts of a provincial young man to rise socially beyond his modest upbringing through a combination of talent, hard work, deception, and hypocrisy. He ultimately allows his passions to betray him.

The novel's full title, Le Rouge et le Noir: Chronique du XIXe siècle (The Red and the Black: A Chronicle of the 19th Century),[2] indicates its twofold literary purpose as both a psychological portrait of the romantic protagonist, Julien Sorel, and an analytic, sociological satire of the French social order under the Bourbon Restoration (1814–30). In English, Le Rouge et le Noir is variously translated as Red and Black, Scarlet and Black, and The Red and the Black, without the subtitle.[3]

The title is taken to refer to the tension between the clerical (black) and secular (red)[4] interests of the protagonist but it could also refer to the then-popular card game "rouge et noir," with the card game being the narratological leitmotiv of a novel in which chance and luck determine the fate of the main character.[5] There are other interpretations as well.[6]

Background[edit]

Le Rouge et le Noir is the Bildungsroman of Julien Sorel, the intelligent and ambitious protagonist. He comes from a poor family[1] and fails to understand much about the ways of the world he sets out to conquer. He harbours many romantic illusions, but becomes mostly a pawn in the political machinations of the ruthless and influential people about him. The adventures of the hero satirize early 19th-century French society, accusing the aristocracy and Catholic clergy of being hypocritical and materialistic, foretelling the radical changes that will soon depose them from their leading roles in French society.

The first volume's epigraph, "La vérité, l'âpre vérité" ("The truth, the harsh truth"), is attributed to Danton, but like most of the chapters' epigraphs it is fictional. The first chapter of each volume repeats the title Le Rouge et le Noir and the subtitle Chronique de 1830. The title refers to the contrasting uniforms of the army and the church. Early in the story, Julien Sorel realistically observes that under the Bourbon Restoration it is impossible for a man of his plebeian social class to distinguish himself in the army (as he might have done under Napoleon), hence only a church career offers social advancement and glory.

In complete editions, the first book ("Livre premier", ending after Chapter XXX) concludes with the quotation "To the Happy Few" from The Vicar of Wakefield by Oliver Goldsmith, parts of which Stendhal had memorized in the course of teaching himself English. In The Vicar, "the happy few" read the title character's obscure and pedantic treatise on monogamy—alone.[7]

Plot[edit]

In two volumes, The Red and the Black: A Chronicle of the 19th Century tells the story of Julien Sorel's life in France's rigid social structure restored after the disruptions of the French Revolution and the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Book I[edit]

Julien Sorel, the ambitious son of a carpenter in the fictional village of Verrières, in Franche-Comté, France, would rather read and daydream about the glorious victories of Napoleon's long-disbanded army than work in his father's timber business with his brothers, who beat him for his intellectual pretensions.[1] He becomes an acolyte of the Abbé Chélan, the local Catholic prelate, who secures for Julien a job tutoring the children of Monsieur de Rênal, the mayor of Verrières. Although representing himself as a pious, austere cleric, Julien is uninterested in religious studies beyond the Bible's literary value and his ability to use memorized Latin passages to impress his social superiors.

He begins a love affair with Monsieur de Rênal's wife, which ends when her chambermaid, Elisa, who is also in love with Julien, makes it known to the village. The Abbé Chélan orders Julien to a seminary in Besançon, which he finds intellectually stifling and populated by social cliques. The initially cynical seminary director, the Abbé Pirard, likes Julien and becomes his protector. When the Abbé, a Jansenist, leaves the seminary, he fears Julien will suffer for having been his protégé and recommends Sorel as private secretary to the diplomat Marquis de la Mole, a Catholic legitimist.

Book II[edit]

In the years leading up to the July Revolution of 1830, Julien Sorel lives in Paris as an employee of the de la Mole family. Despite his sophistication and intellect, Julien is condescended to as an uncouth plebeian by the de la Moles and their friends. Meanwhile, Julien is acutely aware of the materialism and hypocrisy that permeate the Parisian elite and that the counterrevolutionary temper of the time renders it impossible for even well-born men of superior intellect and aesthetic sensibility to participate in the nation's public affairs.

Julien accompanies the Marquis de la Mole to a secret meeting, then is dispatched on a dangerous mission to communicate a letter from memory to the Duc d'Angoulême, who is exiled in England; but the callow Julien is distracted by an unrequited love affair and learns the message only by rote, missing its political significance as part of a legitimist plot. Unwittingly, he risks his life in service to the monarchists he most opposes; to himself, he rationalises these actions as merely helping the Marquis, his employer, whom he respects.

Meanwhile, the Marquis's languorous daughter, Mathilde de la Mole, has become emotionally torn between her romantic attraction to Julien for his admirable personal and intellectual qualities and her revulsion at becoming sexually intimate with a lower-class man. At first Julien finds her unattractive, but his interest is piqued by her attentions and the admiration she inspires in others; twice, she seduces and rejects him, leaving him in a miasma of despair, self-doubt, and happiness (for having won her over her aristocratic suitors). Only during his secret mission does he learn the key to winning her affections: a cynical jeu d'amour (game of love) taught to him by Prince Korasoff, a Russian man-of-the-world. At great emotional cost, Julien feigns indifference to Mathilde, provoking her jealousy with a sheaf of love-letters meant to woo Madame de Fervaques, a widow in the social circle of the de la Mole family. Consequently, Mathilde sincerely falls in love with Julien, eventually revealing to him that she carries his child; nevertheless, while he is on diplomatic mission in England, she becomes officially engaged to Monsieur de Croisenois, an amiable and wealthy young noble, heir to a duchy.

Learning of Julien's liaison with Mathilde, the Marquis de la Mole is angered, but he relents before her determination and his affection for Julien and bestows upon Julien an income-producing property attached to an aristocratic title as well as a military commission in the army. Although ready to bless their marriage, the marquis changes his mind after receiving a character-reference letter about Julien from the Abbé Chélan, Julien's previous employer in Verrières. Written by Madame de Rênal at the urging of her confessor priest, the letter warns the marquis that Julien is a social-climbing cad who preys upon emotionally vulnerable women.

On learning that the marquis now withholds his blessing of his marriage, Julien Sorel returns with a gun to Verrières and shoots Madame de Rênal during Mass in the village church; she survives, but Julien is imprisoned and sentenced to death. Mathilde tries to save him by bribing local officials, and Madame de Rênal, still in love with him, refuses to testify and pleads for his acquittal, aided by the priests who have looked after him since his early childhood. Yet Julien is determined to die, for the materialistic society of Restoration France has no place for a low-born man, whatever his intellect or sensibilities.

Meanwhile, the presumptive duke, Monsieur de Croisenois, one of the fortunate few of Bourbon France, is killed in a duel over a slur upon the honour of Mathilde de la Mole. Her undiminished love for Julien, his imperiously intellectual nature and romantic exhibitionism render Mathilde's prison visits to him a duty to endure and little more.

When Julien learns that Madame de Rênal survived her gunshot wound, his authentic love for her is resurrected, having lain dormant throughout his Parisian sojourn, and she continues to visit him in jail. After he is guillotined, Mathilde de la Mole reenacts the cherished 16th-century French tale of Queen Margot, who visited her dead lover, Joseph Boniface de La Mole, to kiss the forehead of his severed head. Mathilde then erects a shrine at Julien's tomb in the Italian fashion. Madame de Rênal, more quietly, dies in the arms of her children only three days later.

Structure and themes[edit]

Le Rouge et le Noir is set in the latter years of the Bourbon Restoration (1814–30) and the days of the 1830 July Revolution that established the Kingdom of the French (1830–48). Julien Sorel's worldly ambitions are motivated by the emotional tensions between his idealistic Republicanism and his nostalgic allegiance to Napoleon, and the realistic politics of counter-revolutionary conspiracy by Jesuit-supported legitimists, notably the Marquis de la Mole, whom Julien serves for personal gain. Presuming a knowledgeable reader, Stendhal only alludes to the historical background of Le Rouge et le Noir—yet did subtitle the novel Chronique de 1830 ("Chronicle of 1830"). The reader who wants an exposé of the same historical background might wish to read Lucien Leuwen (1834), one of Stendhal's unfinished novels, posthumously published in 1894.

Stendhal repeatedly questions the possibility and the desirability of "sincerity," because most of the characters, especially Julien Sorel, are acutely aware of having to play a role to gain social approval. In that 19th-century context, the word "hypocrisy" denoted the affectation of high religious sentiment; in The Red and the Black it connotes the contradiction between thinking and feeling.

In Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque (Deceit, Desire and the Novel, 1961), philosopher and critic René Girard identifies in Le Rouge et le Noir the triangular structure he denominates as "mimetic desire"; that is, one desires a person only when he or she is desired by someone else. Girard's proposition is that a person's desire for another is always mediated by a third party. This triangulation thus accounts for the perversity of the Mathilde–Julien relationship, which is most evident when Julien begins courting the widow Mme de Fervaques to pique Mathilde's jealousy, and also accounts for Julien's fascination with and membership in the high society he simultaneously desires and despises. To help achieve a literary effect, Stendhal wrote most of the epigraphs—literary, poetic, historic quotations—that he attributed to others.

Literary and critical significance[edit]

André Gide said that The Red and the Black was a novel ahead of its time, that it was a novel for readers in the 20th century. In Stendhal's time, prose novels included dialogue and omniscient narrator descriptions; Stendhal's great contribution to literary technique was the describing of the psychologies (feelings, thoughts, and interior monologues) of the characters. As a result, he is considered the creator of the psychological novel.

In Jean-Paul Sartre's play Les Mains sales (1948), the protagonist Hugo Barine suggests pseudonyms for himself, including "Julien Sorel", whom he resembles.

In the afterword to her novel them, Joyce Carol Oates wrote that she had originally entitled the manuscript Love and Money as a nod to classic 19th-century novels, among them The Red and the Black, "whose class-conscious hero Julien Sorel is less idealistic, greedier, and crueler than Jules Wendall but is clearly his spiritual kinsman."[8]

A passage describing Julien Sorel's sexual indifference is deployed as the epigraph to Paul Schrader's screenplay of American Gigolo, whose protagonist is also named Julien: "The idea of a duty to be performed, and the fear of making himself ridiculous if he failed to perform it, immediately removed all pleasure from his heart."[9]

U.S. Vice President Al Gore named The Red and the Black as his favorite book.[10]

Translations[edit]

Le Rouge et le Noir, Chronique du XIXe siècle (1830) was first translated into English ca. 1900; the best-known translation, The Red and the Black (1926) by C. K. Scott Moncrieff, has been, like his other translations, characterised as one of his "fine, spirited renderings, not entirely accurate on minor points of meaning . . . Scott Moncrieff's versions have not really been superseded."[11] The version by Robert M. Adams for the Norton Critical Editions series is also highly regarded; it "is more colloquial; his edition includes an informative section on backgrounds and sources, and excerpts from critical studies."[12] Other translators include Margaret R. B. Shaw (as Scarlet and Black for Penguin Classics, 1953), Lowell Blair (Bantam Books, 1959), Lloyd C. Parks (New York, 1970), Catherine Slater (Oxford World's Classics, first published 1991), and Roger Gard (Penguin Classics, 2002).

The 2006 translation by Burton Raffel for the Modern Library edition generally earned positive reviews, with Salon.com saying, "[Burton Raffel's] exciting new translation of The Red and the Black blasts Stendhal into the twenty-first century." Michael Johnson, writing in The New York Times, said, "Now 'The Red and the Black' is getting a new lease on life with an updated English-language version by the renowned translator Burton Raffel. His version has all but replaced the decorous text produced in the 1920s by the Scottish-born writer-translator C.K. Scott-Moncrieff".[13]

Burned in 1964 Brazil[edit]

Following the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état, General Justino Alves Bastos, commander of the Third Army, ordered, in Rio Grande do Sul, the burning of all "subversive books." Among the books he branded as subversive was The Red and the Black.[14]

Film adaptations[edit]

- Der geheime Kurier (The Secret Courier) is a silent 1928 German film by Gennaro Righelli, featuring Ivan Mosjoukine, Lil Dagover, and Valeria Blanka.

- Il Corriere del re (The Courier of the King) is a black-and-white 1947 Italian film adaptation of the story also directed by Gennaro Righelli. It features Rossano Brazzi, Valentina Cortese, and Irasema Dilián.

- Another film adaptation of the novel was released in 1954, directed by Claude Autant-Lara. It stars Gérard Philipe, Antonella Lualdi, and Danielle Darrieux. It won the French Syndicate of Cinema Critics award for the best film of the year.

- Le Rouge et le Noir is a 1961 French made-for-TV film version directed by Pierre Cardinal, with Robert Etcheverry, Micheline Presle, Marie Laforêt, and Jean-Roger Caussimon.

- A BBC TV miniseries in five episodes, The Scarlet and the Black, was made in 1965, starring John Stride, June Tobin, and Karin Fernald. It is unknown if the serial still exists, as it has not been seen or documented in decades.

- Красное и чёрное (Krasnoe i čërnoe) (Red and Black) is a 1976 Soviet film version, directed by Sergei Gerasimov, with Nikolai Yeryomenko Ml, Natalya Bondarchuk, and Natalya Belokhvostikova.

- Another BBC TV miniseries called Scarlet and Black was first broadcast in 1993, starring Ewan McGregor, Rachel Weisz, and Stratford Johns as the Abbé Pirard. A notable addition to the plot was the spirit of Napoleon (Christopher Fulford), who advises Sorel (McGregor) through his rise and fall.

- A made-for-TV film version of the novel called The Red and the Black was first broadcast in 1997 by Koch Lorber Films, starring Kim Rossi Stuart, Carole Bouquet, and Judith Godrèche; it was directed by Jean-Daniel Verhaeghe. This version is available on DVD.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Garzanti, Aldo (1974) [1972]. Enciclopedia Garzanti della letteratura (in Italian). Milan: Garzanti. p. 874.

- ^ The Red and the Black, by Stendhal, C. K. Scott-Moncrief, trans., 1926, p. xvi.

- ^ Benét's Reader's Encyclopedia, Fourth Edition, (1996) p. 859.

- ^ "The Red and The Black". www.nytheatre.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ Lubrich, Naomi (2015). «Wie kleidet sich ein Künstler?», in: KulturPoetik 14:2, 2014, 182–204; Naomi Lubrich, Die Feder des Schriftstellers. Mode im Roman des französischen Realismus. Aisthesis. p. 200.

- ^ "Red and Black?"

- ^ Martin Brian Joseph. Napoleonic Friendship: Military Fraternity, Intimacy, and Sexuality in Nineteenth- Century France. UPNE, 2011, p. 123

- ^ Oates, Joyce Carol (21 February 2018). them. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 9780525512561.

- ^ Schrader, Paul. Collected Screenplays 1. Faber and Faber, 2002, p. 123.

- ^ Kurtz, Howard (12 September 2000). "A Moment of Clarity on Candidates' Status". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ The Oxford guide to Literature in English translation, by Peter France, p. 276.

- ^ Stendhal: the red and the black, by Stirling Haig, Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-521-34982-6, and ISBN 978-0-521-34982-6.

- ^ Johnson, Michael (11 September 2008). "Opinion | Stendhal at his best: A 'worthless' historian". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ E. Bradford Burns, A History of Brazil, Columbia University Press, 1993, p. 451.

Bibliography[edit]

- Burt, Daniel S. (2003). The Novel 100. Checkmark Books. ISBN 0-8160-4558-5.

External links[edit]

Media related to The Red and the Black at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Red and the Black at Wikimedia Commons French Wikisource has original text related to this article: The Red and the Black

French Wikisource has original text related to this article: The Red and the Black

- Le Rouge et Le Noir at Project Gutenberg

- (in English)

The Red and the Black public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Red and the Black public domain audiobook at LibriVox - (in French)

Le Rouge et le noir public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Le Rouge et le noir public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Stendhal

Marie-Henri Beyle | |

|---|---|

Stendhal, by Olof Johan Södermark, 1840 | |

| Born | 23 January 1783 Grenoble, Dauphiné, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 23 March 1842 (aged 59) Paris, July Monarchy |

| Resting place | Cimetière de Montmartre |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Literary movement | Realism |

Marie-Henri Beyle (French: [bɛl]; 23 January 1783 – 23 March 1842), better known by his pen name Stendhal (UK: /ˈstɒ̃dɑːl/, US: /stɛnˈdɑːl, stænˈ-/;[1][2][3] French: [stɛ̃dal, stɑ̃dal]),[a] was a 19th-century French writer. Best known for the novels Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black, 1830) and La Chartreuse de Parme (The Charterhouse of Parma, 1839), he is highly regarded for the acute analysis of his characters' psychology and considered one of the early and foremost practitioners of realism. A self-proclaimed egotist, he coined the same characteristic in his characters' "Beylism".[5]

Life[edit]

Born in Grenoble, Isère, he was an unhappy child, disliking his "unimaginative" father and mourning his mother, whom he loved fervently, and who died when he was seven.[6] He spent "the happiest years of his life" at the Beyle country house in Claix near Grenoble.[citation needed] His closest friend was his younger sister, Pauline, with whom he maintained a steady correspondence throughout the first decade of the 19th century. His family was part of the bourgeois class and was attached to the Ancien Regime, which explains his ambiguous attitude toward Napoleon, the Bourbon Restoration, and the monarchy later on.[7]

The military and theatrical worlds of the First French Empire were a revelation to Beyle. He was named an auditor with the Conseil d'État on 3 August 1810, and thereafter took part in the French administration and in the Napoleonic wars in Italy. He travelled extensively in Germany and was part of Napoleon's army in the 1812 invasion of Russia.[8] Upon arriving, Stendhal witnessed the burning of Moscow from just outside the city as well as the army's winter retreat.[9] He was appointed Commissioner of War Supplies and sent to Smolensk to prepare provisions for the returning army.[6] He crossed the Berezina River by finding a usable ford rather than the overwhelmed pontoon bridge, which probably saved his life and those of his companions. He arrived in Paris in 1813, largely unaware of the general fiasco that the retreat had become.[10] Stendhal became known, during the Russian campaign, for keeping his wits about him, and maintaining his "sang-froid and clear-headedness." He also maintained his daily routine, shaving each day during the retreat from Moscow.[11]

After the 1814 Treaty of Fontainebleau, he left for Italy, where he settled in Milan.[12] In 1830, he was appointed as French consul at Trieste and Civitavecchia.[5] He formed a particular attachment to Italy, where he spent much of the remainder of his career. His novel The Charterhouse of Parma, written in 52 days, is set in Italy, which he considered a more sincere and passionate country than Restoration France. An aside in that novel, referring to a character who contemplates suicide after being jilted, speaks about his attitude towards his home country: "To make this course of action clear to my French readers, I must explain that in Italy, a country very far away from us, people are still driven to despair by love."

Stendhal identified with the nascent liberalism and his sojourn in Italy convinced him that Romanticism was essentially the literary counterpart of liberalism in politics.[13] When Stendhal was appointed to a consular post in Trieste in 1830, Metternich refused his exequatur on account of Stendhal's liberalism and anti-clericalism.[14]

Stendhal was a dandy and wit about town in Paris, as well as an obsessive womaniser.[15] His genuine empathy towards women is evident in his books; Simone de Beauvoir spoke highly of him in The Second Sex.[16] She credited him for perceiving a woman as just a woman and simply a human being.[16][17] Citing Stendhal's rebellious heroines, she maintained that he was a feminist writer.[18] One of his early works is On Love, a rational analysis of romantic passion that was based on his unrequited love for Mathilde, Countess Dembowska,[19] whom he met while living at Milan. Later, he would also suffer "restlessness in spirit" when one of his childhood friends, Victorine got married. In a letter to Pauline, he described her as the woman of his dreams and wrote that he would have discovered happiness if he became her husband.[20] This fusion of, and tension between, clear-headed analysis and romantic feeling is typical of Stendhal's great novels; he could be considered a Romantic realist.

Stendhal suffered miserable physical disabilities in his final years as he continued to produce some of his most famous work. He contracted syphilis in December 1808.[21] As he noted in his journal, he was taking iodide of potassium and quicksilver to treat his sexual disease, resulting in swollen armpits, difficulty swallowing, pains in his shrunken testicles, sleeplessness, giddiness, roaring in the ears, racing pulse and "tremors so bad he could scarcely hold a fork or a pen". Modern medicine has shown that his health problems were more attributable to his treatment than to his syphilis. He is said to have sought the best treatment in Paris, Vienna, and Rome.[21]

Stendhal died on 23 March 1842, a few hours after collapsing with a seizure in the street in Paris. He is interred in the Cimetière de Montmartre.

Pseudonyms[edit]

Before settling on the pen name Stendhal, he published under many pen names, including "Louis Alexandre Bombet" and "Anastasius Serpière". The only book that Stendhal published under his own name was The History of Painting (1817). From the publication of Rome, Naples, Florence (September 1817) onwards, he published his works under the pseudonym "M. de Stendhal, officier de cavalerie". He borrowed this pen name from the German city of Stendal, birthplace of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, an art historian and archaeologist famous at the time.[22]

In 1807, Stendhal stayed near Stendal, where he fell in love with a woman named Wilhelmine, whom he called Minette, and for whose sake he remained in the city. "I have no inclination, now, except for Minette, for this blonde and charming Minette, this soul of the north, such as I have never seen in France or Italy."[22] Stendhal added an additional "H" to make the Germanic pronunciation more clear.

Stendhal used many aliases in his autobiographical writings and correspondence, and often assigned pseudonyms to friends, some of whom adopted the names for themselves. Stendhal used more than a hundred pseudonyms, which were astonishingly diverse. Some he used no more than once, while others he returned to throughout his life. "Dominique" and "Salviati" served as intimate pet names. He coins comic names "that make him even more bourgeois than he really is: Cotonnet, Bombet, Chamier."[23]: 80 He uses many ridiculous names: "Don phlegm", "Giorgio Vasari", "William Crocodile", "Poverino", "Baron de Cutendre". One of his correspondents, Prosper Mérimée, said: "He never wrote a letter without signing a false name."[24]

Stendhal's Journal and autobiographical writings include many comments on masks and the pleasures of "feeling alive in many versions." "Look upon life as a masked ball," is the advice that Stendhal gives himself in his diary for 1814.[23]: 85 In Memoirs of an Egotist he writes: "Will I be believed if I say I'd wear a mask with pleasure and be delighted to change my name?...for me the supreme happiness would be to change into a lanky, blonde German and to walk about like that in Paris."[25]

Works[edit]

Contemporary readers did not fully appreciate Stendhal's realistic style during the Romantic period in which he lived. He was not fully appreciated until the beginning of the 20th century. He dedicated his writing to "the Happy Few" (in English in the original). This can be interpreted as a reference to Canto 11 of Lord Byron's Don Juan, which refers to "the thousand happy few" who enjoy high society, or to the "we few, we happy few, we band of brothers" line of William Shakespeare's Henry V, but Stendhal's use more likely refers to The Vicar of Wakefield by Oliver Goldsmith, parts of which he had memorized in the course of teaching himself English.[26]

In The Vicar of Wakefield, "the happy few" refers ironically to the small number of people who read the title character's obscure and pedantic treatise on monogamy.[26] As a literary critic, such as in Racine and Shakespeare, Stendhal championed the Romantic aesthetic by unfavorably comparing the rules and strictures of Jean Racine's classicism to the freer verse and settings of Shakespeare, and supporting the writing of plays in prose.

According to the literary theorist Kornelije Kvas: "In his novel The Red and the Black, Stendhal refers to a novel as a mirror being carried in a basket. The metaphor of the realistic novel as a mirror of contemporary reality, accessible to the narrator, has certain limitations, which the artist is aware of. A valuable realistic work exceeds the Platonic meaning of art as a copy of reality. A mirror does not reflect reality in its entirety, nor is the artist’s aim to document it fully. In The Red and the Black, the writer emphasizes the significance of selection when it comes to describing reality, with a view to realizing the cognitive function of a work of art, achieved through the categories of unity, coherence and typicality".[27] Stendhal was an admirer of Napoleon and his novel Le Rouge et le Noir is considered his literary tribute to the emperor.[28]

Today, Stendhal's works attract attention for their irony and psychological and historical dimensions. Stendhal was an avid fan of music, particularly the works of the composers Domenico Cimarosa, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Gioacchino Rossini. He wrote a biography of Rossini, Vie de Rossini (1824), now more valued for its wide-ranging musical criticism than for its historical content. He also idealized aristocracy, noting its antiegalitarianism but appreciating how it is liberal in its love of liberty.[29]

In his works, Stendhal reprised excerpts appropriated from Giuseppe Carpani, Théophile Frédéric Winckler, Sismondi and others.[30][31][32][33]

Novels[edit]

- Armance (1827)

- Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black, 1830)

- Lucien Leuwen (1835, unfinished, published 1894)

- The Pink and the Green (1837, unfinished)

- La Chartreuse de Parme (1839) (The Charterhouse of Parma)

- Lamiel (1839–1842, unfinished, published 1889)

Novellas[edit]

- Mina de Vanghel (1830, later published in the Paris periodical La Revue des Deux Mondes)

- Vanina Vanini (1829)

- Italian Chroniques, 1837–1839

- Vittoria Accoramboni

- The Cenci (Les Cenci, 1837)

- The Duchess of Palliano (La Duchesse de Palliano)

- The Abbess of Castro (L'Abbesse de Castro, 1832)

Biography[edit]

- A Life of Napoleon (1817–1818, published 1929)

- A Life of Rossini (1824)

Autobiography[edit]

Stendhal's brief memoir, Souvenirs d'Égotisme (Memoirs of an Egotist), was published posthumously in 1892. Also published was a more extended autobiographical work, thinly disguised as the Life of Henry Brulard.

- The Life of Henry Brulard (1835–1836, published 1890)

- Souvenirs d'Égotisme (written in 1832 and published in 1892) (Memoirs of an Egotist)

- Journal (1801–1817) (The Private Diaries of Stendhal)

Non-fiction[edit]

- Rome, Naples et Florence (1817)

- De L'Amour (1822) (On Love [fr])

- Racine et Shakespéare (1823–1835) (Racine and Shakespeare)

- Voyage dans le midi de la France (1838; though first published posthumously in 1930) (Travels in the South of France)

His other works include short stories, journalism, travel books (A Roman Journal), a famous collection of essays on Italian painting, and biographies of several prominent figures of his time, including Napoleon, Haydn, Mozart, Rossini and Metastasio.

Crystallization[edit]

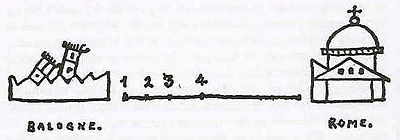

In Stendhal's 1822 classic On Love [fr] he describes or compares the "birth of love", in which the love object is 'crystallized' in the mind, as being a process similar or analogous to a trip to Rome. In the analogy, the city of Bologna represents indifference and Rome represents perfect love:

When we are in Bologna, we are entirely indifferent; we are not concerned to admire in any particular way the person with whom we shall perhaps one day be madly in love; even less is our imagination inclined to overrate their worth. In a word, in Bologna "crystallization" has not yet begun. When the journey begins, love departs. One leaves Bologna, climbs the Apennines, and takes the road to Rome. The departure, according to Stendhal, has nothing to do with one's will; it is an instinctive moment. This transformative process actuates in terms of four steps along a journey:

- Admiration – one marvels at the qualities of the loved one.

- Acknowledgement – one acknowledges the pleasantness of having gained the loved one's interest.

- Hope – one envisions gaining the love of the loved one.

- Delight – one delights in overrating the beauty and merit of the person whose love one hopes to win.

This journey or crystallization process (shown above) was detailed by Stendhal on the back of a playing card while speaking to Madame Gherardi, during his trip to the Salzburg salt mine.

Critical appraisal[edit]

Hippolyte Taine considered the psychological portraits of Stendhal's characters to be "real, because they are complex, many-sided, particular and original, like living human beings." Émile Zola concurred with Taine's assessment of Stendhal's skills as a "psychologist", and although emphatic in his praise of Stendhal's psychological accuracy and rejection of convention, he deplored the various implausibilities of the novels and Stendhal's clear authorial intervention.[34]

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche refers to Stendhal as "France's last great psychologist" in Beyond Good and Evil (1886).[35] He also mentions Stendhal in the Twilight of the Idols (1889) during a discussion of Dostoevsky as a psychologist, saying that encountering Dostoevsky was "the most beautiful accident of my life, more so than even my discovery of Stendhal".[36]

Ford Madox Ford, in The English Novel, asserts that to Diderot and Stendhal "the Novel owes its next great step forward...At that point it became suddenly evident that the Novel as such was capable of being regarded as a means of profoundly serious and many-sided discussion and therefore as a medium of profoundly serious investigation into the human case."[37]

Erich Auerbach considers modern "serious realism" to have begun with Stendhal and Balzac.[38] In Mimesis, he remarks of a scene in The Red and the Black that "it would be almost incomprehensible without a most accurate and detailed knowledge of the political situation, the social stratification, and the economic circumstances of a perfectly definite historical moment, namely, that in which France found itself just before the July Revolution."[39]

In Auerbach's view, in Stendhal's novels "characters, attitudes, and relationships of the dramatis personæ, then, are very closely connected with contemporary historical circumstances; contemporary political and social conditions are woven into the action in a manner more detailed and more real than had been exhibited in any earlier novel, and indeed in any works of literary art except those expressly purporting to be politico-satirical tracts."[39]

Simone de Beauvoir uses Stendhal as an example of a feminist author. In The Second Sex de Beauvoir writes “Stendhal never describes his heroines as a function of his heroes: he provides them with their own destinies.”[40] She furthermore points out that it “is remarkable that Stendhal is both so profoundly romantic and so decidedly feminist; feminists are usually rational minds that adopt a universal point of view in all things; but it is not only in the name of freedom in general but also in the name of individual happiness that Stendhal calls for women’s emancipation.”[40] Yet, Beauvoir criticises Stendhal for, although wanting a woman to be his equal, her only destiny he envisions for her remains a man.[40]

Even Stendhal's autobiographical works, such as The Life of Henry Brulard or Memoirs of an Egotist, are "far more closely, essentially, and concretely connected with the politics, sociology, and economics of the period than are, for example, the corresponding works of Rousseau or Goethe; one feels that the great events of contemporary history affected Stendhal much more directly than they did the other two; Rousseau did not live to see them, and Goethe had managed to keep aloof from them." Auerbach goes on to say:

Vladimir Nabokov was dismissive of Stendhal, in Strong Opinions calling him "that pet of all those who like their French plain". In the notes to his translation of Eugene Onegin, he asserts that Le Rouge et le Noir is "much overrated", and that Stendhal has a "paltry style". In Pnin Nabokov wrote satirically, "Literary departments still labored under the impression that Stendhal, Galsworthy, Dreiser, and Mann were great writers."[41]

Michael Dirda considers Stendhal "the greatest all round French writer – author of two of the top 20 French novels, author of a highly original autobiography (Vie de Henry Brulard), a superb travel writer, and as inimitable a presence on the page as any writer you'll ever meet."[42]

Stendhal syndrome[edit]

In 1817 Stendhal was reportedly overcome by the cultural richness of Florence he encountered when he first visited the Tuscan city. As he described in his book Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio:

The condition was diagnosed and named in 1979 by Italian psychiatrist Dr. Graziella Magherini, who had noticed similar psychosomatic conditions (racing heart beat, nausea and dizziness) amongst first-time visitors to the city.

In homage to Stendhal, Trenitalia named their overnight train service from Paris to Venice the Stendhal Express, though there is no physical distress connected to it.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The pronunciation [stɛ̃dal] is the most common in France today, as shown by the entry stendhalien ([stɛ̃daljɛ̃]) in the Petit Robert dictionary and by the pronunciation recorded on the authoritative website Pronny the pronouncer,[4] which is run by a professor of linguistics and records the pronunciations of highly educated native speakers. The pronunciation [stɑ̃dal] is less common in France today, but was presumably the most common one in 19th-century France and perhaps the one preferred by Stendhal, as shown by the at the time well-known phrase "Stendhal, c'est un scandale" as explained on page 88 of Haig, Stirling (22 June 1989). Stendhal: The Red and the Black. ISBN 9780521349826 by Stirling Haig. On the other hand, many obituaries used the spelling Styndal, which clearly indicates that the pronunciation [stɛ̃dal] was also already common at the time of his death (see Literaturblatt für germanische und romanische Philologie (in German). Vol. 57 to 58. 1936. p. 175). Since Stendhal had lived and traveled extensively in Germany, it is of course also possible that he in fact pronounced his name as the German city [ˈʃtɛndaːl] using /ɛn/ instead of /ɛ̃/ (and perhaps also with /ʃ/ instead of /s/) and that some French speakers approximated this but that most used one of the two common French pronunciations of the spelling -en- ([ɑ̃] and [ɛ̃]).

- ^ Angela Pietragrua is cited twice: during their first meeting in 1800; and when he fell in love with her in 1811.

References[edit]

- ^ "Stendhal: definition of Stendhal in Oxford dictionary (British & World English) (US)". Oxforddictionaries.com. 2014-01-23. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved 2014-01-28.

- ^ "Stendhal: definition of Stendhal in Oxford dictionary (American English) (US)". Oxforddictionaries.com. 2014-01-23. Archived from the original on March 26, 2013. Retrieved 2014-01-28.

- ^ "Stendhal - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2014-01-28.

- ^ "Stendhal". Pronny the pronouncer.

- ^ a b Times, The New York (2011). The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge: A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind. New York: St. Martin's Publishing Group. p. 1334. ISBN 978-0-312-64302-7.

- ^ a b Nemo, August (2020). Essential Novelists - Stendhal: modern consciousness of reality. Tacet Books. ISBN 978-3-96799-211-3.

- ^ Brombert, Victor (2018). Stendhal: Fiction and the Themes of Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-226-53829-7.

- ^ Talty 2009, p. 228 "...the novelist Stendhal, an officer in the commissariat, who was still among the luckiest men on the retreat, having preserved his carriage.".

- ^ Haig, Stirling (1989). Stendhal: The Red and the Black. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-521-34189-2.

- ^ Markham, J. David (April 1997). "Following in the Footsteps of Glory: Stendhal's Napoleonic Career". Napoleonic Scholarship: The Journal of the International Napoleonic Society. 1 (1). Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ Sartre, Jean-Paul (September–October 2009). "War Diary". New Left Review (59): 88–120. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ Bamforth, Iain (2010-12-01). "Stendhal's Syndrome". The British Journal of General Practice. 60 (581): 945–946. doi:10.3399/bjgp10X544780. ISSN 0960-1643. PMC 2991758.

- ^ Green 2011, p. 158.

- ^ Green 2011, p. 239.

- ^ LaPointe, Leonard L. (2012). Paul Broca and the Origins of Language in the Brain. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-59756-604-9.

- ^ a b Leighton, Jean (1975). Simone de Beauvoir on Woman. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-8386-1504-1.

- ^ Rass, Rebecca (2020). Study Guide to The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir. Nashville: Influence Publishers. ISBN 978-1-64542-393-5.

- ^ Pearson, Roger (2014). Stendhal: The Red and the Black and The Charterhouse of Parma. Oxon: Routledge. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-582-09616-5.

- ^ The Fortnightly Review. Suffolk: Chapman and Hall. 1913. p. 74.

- ^ Green, F. C. (1939). An Amharic Reader. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-107-60072-0.

- ^ a b Green, F.C. (1939). Stendhal. Cambridge: CUP Archive. p. 67.

- ^ a b Richardson, Joanna (1974). Stendhal. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan. p. 68.

- ^ a b Starobinski, Jean (1989). "Pseudononimous Stendhal". The Living Eye. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-53664-9.

- ^ Di Maio, Mariella (2011). "Preface". Aux âmes sensibles, Lettres choisies. Gallimard. p. 19.

- ^ Stendhal (1975). "Chapter V". Memoirs of an Egotist. Translated by Ellis, David. Horizon. pp. 63. ISBN 9780818002243.

- ^ a b Martin 2011, p. 123.

- ^ Kvas, Kornelije (2020). The Boundaries of Realism in World Literature. Lanham, Boulder, New York, London: Lexington Books. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-7936-0910-6.

- ^ Clarke, Stephen (2015). How the French Won Waterloo - or Think They Did. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4735-0636-7.

- ^ Goodheart, Eugene (2018). Modernism and the Critical Spirit. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-30910-3.

- ^ Randall, Marilyn (2001). Pragmatic plagiarism: authorship, profit, and power. University of Toronto Press. p. 199. ISBN 9780802048141.

If the plagiarisms of Stendhal are legion, many are virtually translations: that is, cross-border plagiarism. Maurevert reports that Goethe, commenting enthusiastically on Stendhal's Rome, Naples et Florence, notes in a letter to a friend: 'he knows very well how to use what one reports to him, and, above all, he knows well how to appropriate foreign works. He translates passages from my Italian Journey and claims to have heard the anecdote recounted by a marchesina.'

- ^ Victor Del Litto in Stendhal (1986) p.500, quote (translation by Randall 2001 p.199): "used the texts of Carpani, Winckler, Sismondi et 'tutti quanti', as an ensemble of materials that he fashioned in his own way. In other words, by isolating his personal contribution, one arrives at the conclusion that the work, far from being a cento, is highly structured such that even the borrowed parts finally melt into a whole a l'allure bien stendhalienne."

- ^ Hazard, Paul (1921). Les plagiats de Stendhal.

- ^ Dousteyssier-Khoze, Catherine; Place-Verghnes, Floriane (2006). Poétiques de la parodie et du pastiche de 1850 à nos jours. p. 34. ISBN 9783039107438.

- ^ Pearson, Roger (2014). Stendhal: "The Red and the Black" and "The Charterhouse of Parma". Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 978-0582096165.

- ^ Nietzsche 1973, p. 187.

- ^ Nietzsche 2004, p. 46.

- ^ Wood, James (2008). How Fiction Works. Macmillan. p. 165. ISBN 9780374173401.

- ^ Wood, Michael (March 5, 2015). "What is concrete?". The London Review of Books. 37 (5): 19–21. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ a b c Auerbach, Erich (May 2003). Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 454–464. ISBN 069111336X.

- ^ a b c De Beauvoir, Simone (1997). The Second Sex. London: Vintage. ISBN 9780099744214.

- ^ Wilson, Edmund (July 15, 1965). "The Strange Case of Pushkin and Nabokov". nybooks.com. The New York Review of Books. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ Dirda, Michael (June 1, 2005). "Dirda on Books". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ Stendhal. Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio.

Works cited[edit]

- Green, F. C. (16 June 2011). Stendhal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60072-0.

- Martin, Brian Joseph (2011). Napoleonic Friendship: Military Fraternity, Intimacy, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-century France. UPNE. ISBN 978-1-58465-944-0.

- Maurevert, Georges (1922). Le Livre Des Plagiats (in French). A. Fayard & cie.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm (1973). Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future. Translated by Hollingdale, R. J. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-044267-0.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm (1 January 2004). Twilight of the Idols and the Antichrist. Translated by Common, Thomas. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-43460-5.

- Talty, Stephan (2 June 2009). The Illustrious Dead: The Terrifying Story of How Typhus Killed Napoleon's Greatest Army. Crown. ISBN 978-0-307-45975-6.

https://foundation.wikimedia.org/wiki/Terms_of_Use

Further reading[edit]

- Stendhal; Del Litto, Victor; Abravanel, Ernest (1970). Vies de Haydn, de Mozart et de Métastase (in French). Vol. 41. le Cercle du bibliophile.

- Adams, Robert M., Stendhal: Notes on a Novelist. New York, Noonday Press, 1959.

- Blum, Léon, Stendhal et le beylisme. Paris, Paul Ollendorf, 1914.

- Dieter, Anna-Lisa, Eros - Wunde - Restauration. Stendhal und die Entstehung des Realismus, Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, 2019 (Periplous. Münchener Studien zur Literaturwissenschaft).

- Jefferson, Ann. Reading Realism in Stendhal (Cambridge Studies in French). Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Keates, Jonathan. Stendhal. London, Sinclair-Stevenson, 1994.

- Levin, Harry. Toward Stendhal. New York, 1945.

- Richardson, Joanna. Stendhal. London, Victor Gollancz, 1974.

- Tillett, Margaret. Stendhal: The Background to the Novels. Oxford University Press, 1971.

External links[edit]

- Works by Stendhal at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Stendhal at Internet Archive

- Works by Stendhal at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- StendhalForever.com

- Stendhal's works: text, concordances and frequency list

- (in French) Audio Book (mp3) of The Red and the Black incipit

- (in French) French site on Stendhal

- Centro Stendhaliano di Milano Digital version of Stendhal's shoulder-notes on his own books.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Stendhal

- 1783 births

- 1842 deaths

- Writers from Grenoble

- 19th-century French writers

- Conseil d'État (France)

- French agnostics

- French novelists

- French psychological fiction writers

- French biographers

- French travel writers

- Romanticism

- Burials at Montmartre Cemetery

- French male essayists

- French male novelists

- French male short story writers

- 19th-century French short story writers

- French military personnel of the Napoleonic Wars

- Male biographers

- 19th-century pseudonymous writers