Eugène-François Vidocq (French: [øʒɛn fʁɑ̃nswa vidɔk]; 24 July 1775 – 11 May 1857) was a French criminal turned criminalist, whose life story inspired several writers, including Victor Hugo, Edgar Allan Poe and Honoré de Balzac. The former criminal became the founder and first director of France's first criminal investigative agency, the Sûreté nationale, as well as the head of the first known private detective agency. Vidocq is considered to be the father of modern criminology[1][2] and of the French national police force.[3] He is also regarded as the first private detective.[4]

Biography[edit]

Eugène François Vidocq was born in Arras, northern France, during the night of 23/24 July 1775, in the Rue du Miroir-de-Venise, nowadays the Rue Eugène-François Vidocq.[5] He was the third child of Henriette Françoise Vidocq (maiden name Dion, 1744–1824) and her husband, the baker Nicolas Joseph François Vidocq (1744–1799).

Childhood and youth (1775–1795)[edit]

Little is known about his childhood; most of it is based on his ghost-written autobiography and a few documents in French archives. His father was well educated and, for those days, very wealthy, since he was also a corn dealer. Vidocq had six siblings: two older brothers (one of whom had died before he was born), two younger brothers and two younger sisters.

Vidocq's teenage years were a turbulent time period. He is described as being fearless, rowdy and cunning, very talented, but also very lazy. He spent much time in the armories (fighting halls) of Arras and acquired a reputation as a formidable fencer and the nickname le Vautrin ("wild boar"[N 1]). By stealing, he provided himself with some level of comfort.

When Vidocq was thirteen years old, he stole his parents' silver plates and spent the proceeds from them within a day. Three days after the theft, he was arrested and brought to the local jail, Baudets.[N 2] Only ten days later, he learned that his father had arranged his arrest to teach him a lesson. After a total of fourteen days, he was released from prison, but even this did not tame him.

By age fourteen, he had stolen a large amount of money from the cash box of his parents' bakery and left for Ostend, where he tried to embark to the Americas; but he was defrauded one night and found himself suddenly penniless. To survive, he worked for a group of traveling entertainers. Despite regular beatings, he worked hard enough to get promoted from stable boy to playing a Caribbean cannibal who eats raw meat. He ended up living with puppeteers to get away from them. However, he was banished from them because he flirted with the young wife of his employer. He then worked some time as an assistant of a peddler, but as soon as he neared Arras, he returned to his parents seeking forgiveness. He was welcomed by his mother with open arms.

On 10 March 1791, he enlisted in the Bourbon Regiment, where his reputation as an expert fencer was confirmed. According to Vidocq, within six months, he challenged fifteen people to a duel and killed two. Despite not being a model soldier and causing difficulties, he spent only a total of fourteen days in jail. During those two weeks, Vidocq helped a fellow inmate successfully escape.

When France declared war against Austria on 20 April 1792, Vidocq participated in the battles of the First Coalition, including the Battle of Valmy in September 1792. On 1 November 1792, he was promoted to corporal of grenadiers, but during his promotion ceremony, he challenged a fellow non-commissioned officer to a duel. This sergeant major refused the duel. So Vidocq hit him. Striking a superior officer could have led to a death sentence. So he deserted and enlisted in the 11th Chasseurs, concealing his history. On 6 November 1792, he fought under General Dumouriez in the Battle of Jemappes.

In April 1793, Vidocq was identified as a deserter. He followed a general, who was fleeing after a failed martial coup, into the enemy camp. After a few weeks, Vidocq returned to the French camp. A chasseur-captain friend interceded for him. So he was allowed to rejoin the chasseurs. Finally, he resigned from the army because he was no longer welcome.

He was eighteen years old when he returned to Arras. He soon gained a reputation as a womanizer. Since his seductions often ended in duels, he was imprisoned in Baudets from 9 January 1794 to 21 January 1795.[citation needed]

On 8 August 1794, when he was barely nineteen, Vidocq married Anne Marie Louise Chevalier, after a pregnancy scare. No child resulted, and the marriage was not happy from the start, and when Vidocq learned that his wife had cheated on him with the adjutant, Pierre Laurent Vallain, he left again for the army. He did not see his wife again until their divorce in 1805.

Years of wandering and prison (1795–1800)[edit]

Vidocq did not stay long in the army. In autumn 1794, he spent most of his time in Brussels, which was then a hideout for crooks of all kinds. There, he supported himself by small frauds. One day, he was apprehended by the police, and as a deserter, he had no valid papers. When asked for his identity, he described himself as Monsieur Rousseau from Lille and escaped while the police tried to confirm his statement.

In 1795, still under the alias of Rousseau, he joined the armée roulante ("flying army"). This army consisted of "officers" who in reality had neither commissions nor regiments. They were raiders, forging routes, ranks and uniforms but staying away from the battlefields. Vidocq began as a lieutenant of chasseurs but soon promoted himself to a hussar captain. In this role, he met a rich widow in Brussels[N 3] who became fond of him. A co-conspirator of Vidocq's convinced her that Vidocq was a young nobleman on the run because of the French Revolution. Shortly before their wedding, Vidocq confessed to her. Then he left the city, but not without a generous cash gift from her.

In March 1795, Vidocq moved to Paris, where he squandered all his money entertaining women. He went back north and joined a group of Bohemian gypsies, which he later left for a woman he had fallen in love with, Francine Longuet. When Francine left him for a real soldier, he beat both of them. The soldier sued him, and in September 1795, Vidocq was sentenced to three months in the prison Tour Saint-Pierre in Lille.

Vidocq was twenty and quickly adapted to life in prison. He befriended a group of men, among them Sebastien Boitel, who had been sentenced to six years for stealing. Then Boitel was suddenly released, but the next day, the local inspector noticed that the pardon was forged. Vidocq claimed two fellow inmates, Grouard and Herbaux, had asked to use his cell (as a soldier, Vidocq had a cell all to himself) to write something of an unknown nature because the common room was too noisy. Both inmates claimed, however, that he helped in the fabrication and that the whole thing had been his idea. Thus, Vidocq was not released after the three months.

In the following weeks, Vidocq escaped several times with the help of Francine, but was always captured soon again. After one of his escapes, Francine caught him with another woman. He disappeared for a few days, and when he was finally picked up again by police, he was told that Francine had been found with multiple knife wounds. Now, he was not only accused of forgery but also attempted murder. Francine later claimed that the wounds were self-inflicted and the charge was dropped. Vidocq's contact with Francine stopped when she was convicted and sentenced to six months in prison for aiding the escapes.

After a long delay, his trial for document forgery began. On 27 December 1796, Vidocq and a second accused, César Herbaux, were found guilty and sentenced to eight years of hard labour.

In the prison of Bicêtre, Vidocq was to wait several months for the transfer to the Bagne in Brest to toil in the galleys. A fellow inmate taught him the martial art of savate, which was later to prove useful to him. An escape attempt on 3 October 1797 failed and precipitated his placement in a dungeon for eight days.

Finally, on 21 November, he was sent to Brest. On 28 February 1798, he escaped dressed as a sailor. Only a few days later, he was apprehended due to a lack of papers, but the police did not recognize him as an escaped convict. He claimed to be Auguste Duval, and while officials checked this claim, he was put into a prison hospital. There he stole a nun's habit and escaped in disguise. In Cholet, he found a job as a cattle drover and, in this capacity, passed through Paris, Arras, Brussels, Ancer and finally Rotterdam, where he was shanghaied by the Dutch. After a short career as a privateer, he was arrested again and taken to Douai, where he was identified as Vidocq. He was transferred to the Bagne in Toulon, arriving on 29 August 1799. After a failed escape attempt, he escaped again on 6 March 1800 with the help of a prostitute.

The turnaround (1800–1811)[edit]

Vidocq returned to Arras in 1800. His father had died in 1799. So he hid in his mother's house for almost half a year before he was recognized and had to flee again. He assumed the identity of an Austrian and spent some time in a relationship with a widow, with whom he moved to Rouen in 1802. Vidocq built up a reputation as a businessman and finally felt secure enough to let his mother come live with him and the widow; but finally, his past caught up with him. He was arrested and brought to Louvres. There, he learned that he had been sentenced to death in absentia. With the help of the local procurator-general, Ransom, he filed an appeal and spent the following five months in prison waiting for a retrial. During this time, Louise Chevalier contacted him to inform him of their divorce. When it seemed that there would be no decision concerning his sentence, he decided to flee again. On 28 November 1805, while unattended for a moment, he jumped out of a window into the adjacent river Scarpe. For the next four years, he was a man on the run once again.

He spent some time in Paris, where he witnessed the execution of César Herbaux, the man with whom his life had started a downward spiral. This event triggered a process of re-evaluation in Vidocq. With his mother and a woman he called Annette in his memoirs, he moved several times in the following years; but again and again, people from his past recognized him. He again tried to become a legitimate merchant, but his former wife found him in Paris and blackmailed him for money, and a couple of former fellow convicts forced him to fence stolen goods for them.

On 1 July 1809, only a few days before his 34th birthday, Vidocq was arrested again. He decided to stop living on the fringes of society and offered his services as an informant to the police. His offer was accepted, and on 20 July, he was jailed in Bicêtre, where he started his work as a spy. On 28 October, he continued his work in La Force Prison. He sounded out his inmates and forwarded his information about forged identities and unsolved crimes through Annette to the police chief of Paris, Jean Henry.

After 21 months of spying, Vidocq was released from jail on the recommendation of Henry. So as not to raise suspicions among the other inmates, the release (which took place on 25 March 1811) was arranged to look like an escape. Still, Vidocq was not really free, because now he was obliged to Henry. Therefore, he continued to work as a secret agent for the Paris police. He used his contacts and his reputation in the criminal underworld to gain trust. He disguised himself as an escaped convict and immersed himself in the criminal scene to learn about planned and committed crimes. He even took part in felonies in order to suddenly turn on his partners and arrest them. When criminals eventually began to suspect him, he used disguises and assumed other identities to continue his work and throw off suspicion.

The Sûreté (1811–1832)[edit]

At the end of 1811, Vidocq informally organized a plainclothes unit, the Brigade de Sûreté ("Security Brigade"). The police department recognized the value of these civil agents, and in October 1812, the experiment was officially converted to a security police unit under the Prefecture of Police. Vidocq was appointed its leader. On 17 December 1813, Emperor Napoleon I signed a decree that made the brigade a state security police force. From this day on, it was called the Sûreté Nationale.

The Sûreté initially had eight, then twelve, and, in 1823, twenty employees. A year later, it expanded again, to 28 secret agents. In addition, there were eight people who worked secretly for the Sûreté, but instead of a salary, they received licences for gambling halls. A major portion of Vidocq's subordinates were ex-criminals like himself. He even hired them fresh from the prisons; for example, Coco Lacour, who would later become Vidocq's successor at the Sûreté. Vidocq described his work from this period:

Vidocq personally trained his agents, for example, in selecting the correct disguise based on the kind of job. He himself still went out hunting for criminals too. His memoirs are full of stories about how he outsmarted crooks by pretending to be a beggar or an old cuckold. At one point, he even faked his own death.

During 1814, at the beginning of the French Restoration, Vidocq and the Sûreté tried to contain the situation in Paris. He also arrested those who tried to exploit the post-revolutionary situation by claiming to have been aristocrats. During 1817, he was involved in 811 arrests, including those of 15 assassins and 38 fences. By 1820, his activities had reduced crime in Paris substantially. His annual income was 5,000 francs, but he also worked as a private investigator for fees. Rumors at the time claimed that Vidocq set criminals up, organizing break-ins and robberies and having his agents wait to collect the offenders. Even though some of Vidocq's techniques might have been questionable, there seems to be no truth to this.

Despite his position as chief of a police authority, Vidocq remained a wanted criminal. His forgery conviction had never been fully dismissed. So alongside complaints and denunciations, his superiors repeatedly received requests from the prison director of Douai, which they ignored. Finally, the Comte Jules Anglès, prefect of the Paris police, responded to a petition from Vidocq and requested an official pardon, which he received on 26 March 1817 from King Louis XVIII.

In November 1820, Vidocq married again, this time the destitute Jeanne-Victoire Guérin, whose origin is unknown, which at that time led to speculation. She came to live in the household at 111 Rue de l'Hirondelle, where Vidocq's mother and a niece of hers, the 27-year-old Fleuride Albertine Maniez (born March 22, 1793), also lived. In 1822, Vidocq befriended the author Honoré de Balzac, who began to use him as a model for several figures in his books. Vidocq's wife, who was ailing throughout their marriage, died in June 1824 in a hospital. Six weeks later, on 30 July 1824, Vidocq's mother died at age 80. She was buried with honours, and her requiem was performed in Notre Dame Cathedral.

Events of the 1820s affected the police apparatus. After the assassination of the Duc de Berry in February 1820, Police Prefect Anglès had to resign and was replaced by the Jesuit Guy Delavau, who set a high value on religiousness among his subordinates. In 1824, Louis XVIII died. His successor was the ultra-reactionary Charles X, during whose oppressive reign police agents were regularly withdrawn from their original activities.[clarification needed] Finally, Vidocq's immediate superior, police chief Henry, retired and was succeeded by Parisot, who was soon superseded by the ambitious but also very formal Marc Duplessis. The antipathy between Vidocq and Duplessis was great. Time and time again, Duplessis complained about trivial matters, for example, that Vidocq's agents spent time in brothels and bars of ill repute. Vidocq's explanation that they had to do this to establish contacts and gather information was ignored. When Vidocq received two official warnings within a short time, he had had enough. On 20 June 1827, the 52-year-old handed in his resignation:

He then wrote his memoirs with the help of a ghostwriter.

Vidocq, who was a rich man after his resignation, became an entrepreneur. In Saint-Mandé, a small town east of Paris where he married his cousin Fleuride Maniez on 28 January 1830, he founded a paper factory. He mainly employed released convicts – both men and women. This caused an outrageous scandal in society and led to disputes. In addition, the machines cost money, the semi-skilled workers needed food and clothing, and the customers refused to pay marked prices with the argument that he had a seemingly cheaper workforce. The company did not last long; Vidocq went bankrupt in 1831. In the short time while he was away from Paris, both Delavau and Duplessis had to resign their posts, and the July Revolution of 1830 forced Charles X to abdicate. When Vidocq delivered a few useful tips that helped to solve a burglary in Fontainebleau and led to the arrest of eight people, the new police prefect, Henri Gisquet, again appointed him chief of the Sûreté.[7][8]

Criticism of Vidocq and his organization grew. The July Monarchy caused insecurities in society, and there was a cholera outbreak in 1832. One of its victims was General Jean Maximilien Lamarque. During his funeral on 5 June 1832, a revolt erupted and the throne of "Citizen King" Louis-Philippe I was in danger. Allegedly Vidocq's group cracked down on the rioters with great severity. Not all of the police approved of his methods, and rivalries developed. A rumour arose that Vidocq had initiated the theft that led to his reinstatement himself to show his indispensability. One of his agents had to go to prison for two years because of that affair, but Vidocq's involvement could not be proved. More and more defenders[clarification needed] claimed that Vidocq and his agents were not credible as eyewitnesses, since most of them had criminal pasts themselves. Vidocq's position was untenable, and on 15 November 1832, he once again resigned, using the pretext of his wife being ill.

On the same day, the Sûreté was dissolved, then re-established without agents with criminal records, no matter how minor their offenses. Vidocq's successor was Pierre Allard.

Le bureau des renseignements (1833–1848)[edit]

In 1833, Vidocq founded Le bureau des renseignements ("Office of Information"), a company that was a mixture of a detective agency and a private police force. It is considered to be the first known detective agency.[8] Once again, he predominantly hired ex-convicts.

His squad, which initially consisted of eleven detectives, two clerks and one secretary, pitted itself on behalf of businesspeople and private citizens against Faiseurs (crooks, fraudsters, and bankruptcy artists), occasionally using illegal means. From 1837, Vidocq quarreled constantly with the official police because of his activities and his questionable relations with various government agencies such as the War Department. On 28 November 1837, the police executed a search and seizure and confiscated over 3,500 files and documents. A few days later, Vidocq was arrested and spent Christmas and New Year in jail. He was charged with three crimes, namely the acquisition of money by deception, corruption of civil servants, and the pretension of public functions.[clarification needed] In February 1838, after numerous witnesses had testified, the judge dismissed all three charges. Vidocq was free again.

Vidocq increasingly became the subject of literature and public discussions. Balzac wrote several novels and plays that contained characters modeled after Vidocq.

The agency flourished, but Vidocq continued to make enemies, some of them powerful. On 17 August 1842, on behalf of Police Prefect Gabriel Delessert, 75 police officers stormed his office building and arrested him and one of his agents. This time, the case seemed to be clear. In an investigation of defalcation, he had made an illegal arrest and had demanded a bill of exchange for the embezzled money from the arrested fraudster. For the next few months, 67-year-old Vidocq was remanded into custody in the Conciergerie. On 3 May 1843, the first hearings finally took place before judge Michel Barbou, a close friend of Delessert. During the trial, Vidocq had to give testimony about many other cases, among them, the kidnappings of several women whom he had allegedly delivered to monasteries against their will at the behest of their families. Also, his activities as a money lender and the possible benefits from it were examined. Finally, he was sentenced to five years imprisonment and a fine of 3,000 francs. Vidocq immediately appealed, and through the intervention of political friends like Count Gabriel de Berny and the attorney general, Franck-Carré, he quickly got a new trial, this time with the chief judge of the court royale.[clarification needed] The hearing on 22 July 1843 took a matter of minutes, and after eleven months in the Conciergerie, Vidocq was free once again.

The harm was done, however. The lawsuit had been very expensive, and his reputation was damaged. Business at the agency suffered. Moreover, Delessert tried to get him expelled from the city for being a former criminal. Although the attempt failed, Vidocq increasingly considered selling his agency, but he could not find a qualified and reputable buyer.

In the following years, Vidocq published several small books in which he depicted his life to directly refute the rumours that were being circulated about him. In 1844, he presented an essay on prisons, penitentiaries, and the death penalty. On the morning of 22 September 1847, his third wife, Fleuride, died after 17 years of marriage. Vidocq did not marry again, but until his death, he had several intimate partners.

In 1848, the February revolution caused the abdication of "Citizen King" Louis-Philippe. The Second Republic was proclaimed, with Alphonse de Lamartine as the head of a transitional government. Although Vidocq had always been proud of his reception at the king's court and had boasted about his access to Louis-Philippe, he offered his services to the new government. His task was the surveillance of political opponents such as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon I. Meanwhile, the new government sank into chaos and violence. In the presidential election of 10 December 1848, Lamartine received less than 8,000 votes. Vidocq presented himself as a candidate in the 2nd Arrondissement but received only one vote. The clear winner, and thus president of the Second Republic, was Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, who did not respond to Vidocq's offer to work for him.

Last years (1849–1857)[edit]

In 1849, Vidocq briefly went to prison one last time, on a charge of fraud. In the end, however, the case was dropped. He withdrew more and more into private life and accepted only small cases every now and then. In the last years of his life, he suffered great pain in his right arm, which had been broken and had never healed properly. Also, unwise investments had cost him a large portion of his assets. So he had to curb his living standard and live in rented accommodations. In August 1854, despite a pessimistic prognosis by his doctor, he survived a bout of cholera. Only in April 1857 did his condition deteriorate to the point he could no longer stand. On 11 May 1857, Vidocq died at the age of 81 in his home in Paris in the presence of his doctor, his lawyer and a priest.

His body was brought to the church of Saint-Denys du Saint-Sacrement, where the funeral service was held. It is not known where Vidocq is buried, though there are some rumours as to the location. One of them, mentioned in the biography of Philip John Stead, claims that his grave is at the cemetery in Saint Mandé.[10] There is a gravestone with the inscription "Vidocq 18". According to information from city officials, however, this grave is registered to Vidocq's last wife, Fleuride-Albertine Maniez.

In the end, his assets consisted of 2,907.50 francs from the sale of his goods and a pension of 867.50 francs.[8] A total of eleven women came forward as owners of his testament, a document which they had received for their favours instead of presents. His remaining assets went to Anne-Heloïse Lefèvre, at whose house he had lived at the end of his life. Although Vidocq had no known children, Emile-Adolphe Vidocq, the son of his first wife, tried to get recognized as his son (even changing his last name for this purpose), but failed. Vidocq had left evidence which ruled out his paternity: he had been in prison at the time of Emile-Adolphe Vidocq's conception.

Criminology legacy[edit]

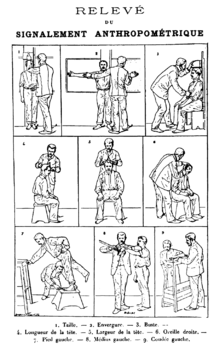

Vidocq is considered by historians as the "father" of modern criminology.[1][2] His approaches were new and unique for that time. However, it should be said that a famous predecessor Antoine de Sartine who organised the secret police under the monarchy before the French Revolution influenced other governments of Europe, Catherine II of Russia, Maria Theresa of Austria, and the Pope. De Sartine is portrayed in the fictional detective French TV series Nicolas Le Floch. Nonetheless, Vidocq is credited with the introduction of undercover work, ballistics, criminology and a record keeping system to criminal investigation. He made the first plaster cast impressions of shoe prints. He created indelible ink and unalterable bond paper with his printing company. His form of anthropometrics is still partially used by French police. He is also credited with philanthropic pursuits – he claimed he never informed on anyone who had stolen out of real need.

At the same time, his work was not acknowledged in France for a long time because of his criminal past. In September 1905, the Sûreté Nationale exhibited a painting series with its former heads. However, the first painting of the series showed Pierre Allard, Vidocq's successor. The newspaper L'Exclusive reported on 17 September 1905 that on obtaining information concerning the omission, they had gotten the answer that Vidocq had never been head of the Sûreté.

Remodelling of the police force[edit]

When Vidocq gave his allegiance to the police around 1810, there were two police organizations in France: on the one side, there was the police politique, an intelligence agency whose agents were responsible for the detection of conspiracies and intrigues; on the other, the normal police, who investigated common crimes such as theft, fraud, prostitution, and murder. Since the Middle Ages, those constables wore identification insignia that, over time, had developed to full uniforms. Unlike the often covertly operating political police, they were easy to spot. For fear of attack, they did not dare to enter some Parisian districts, limiting their efforts at crime prevention.

Vidocq persuaded his superiors to allow his agents, who also included women, to wear plain clothes and disguises depending on the situation. Thus, they did not attract attention and, as former criminals, also knew the hiding places and methods of criminals. Through their contacts, they often learned of planned crimes and were able to catch the guilty red-handed. Vidocq also had a different approach to interrogation. In his memoirs, he mentions several times that he did not take those arrested to prison immediately, but invited them to dinner, where he chatted with them. In addition to information about other crimes, he often obtained confessions in this non-violent way and recruited future informants and even agents.

August Vollmer, the first police chief of Berkeley, California, and a leading figure in the development of criminal justice in the United States,[11] studied the works of Vidocq and the Austrian criminal jurist Hans Gross for his reform of the Berkeley police force.[12] His reform ideas were adopted by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) and, as a result, also affected J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI.[13] After Robert Peel established Scotland Yard in 1829, he sent a committee to Paris in 1832 to confer with Vidocq for several days.[citation needed] In 1843, two commissars[clarification needed] of Scotland Yard traveled to Paris for further training. They spent only two days with Pierre Allard, who was head of the Sûreté by then[citation needed]. Then they went to Vidocq's private agency and, for one week, accompanied him and his agents in their work.[14]

Identification of criminals[edit]

Jürgen Thorwald stated in his book Das Jahrhundert der Detektive (1964) that Vidocq had a photographic memory that allowed him to recognize previously convicted criminals, even in disguise. Biographer Samuel Edwards reported in The Vidocq Dossier about a trial against the fraudster and forger Lambert, in which Vidocq referred to his memory of the accused. Vidocq regularly visited the prisons to memorise the faces of the inmates and made his agents do the same. The English police adopted this method. Until the late 1980s, British investigators attended court hearings to observe the spectators in the public galleries and become aware of possible accomplices.

As Vidocq said at Lambert's trial, while his memory was phenomenal, he could not require the same of his agents. Therefore, for each arrested person, he carefully set up an index card with a personal description, aliases, previous convictions, modus operandi, and other information. The card of forger Lambert contained, among other things, a handwriting sample. The index card system was retained not only by the French police, but also by police units in other countries. However, it soon revealed its weaknesses. By the time Alphonse Bertillon came to the Sûreté as clerk in 1879, the descriptions on the cards were not detailed enough anymore to really identify suspects. This caused Bertillon to develop an anthropometric system for personal identification called the bertillonage. The sorting of the card boxes, which by then already filled several rooms, was converted to body dimensions, the first of many attempts to improve the structure of the sorting. With the advent of the information age, the cards were digitised, and the card boxes were replaced by databases.

Scientific experiments[edit]

Forensic science did not yet exist during Vidocq's time. Despite numerous scientific papers, the police did not recognize its practical benefits, and this could not be changed by Vidocq. Nevertheless, he was not so averse to experiments as his superiors and usually had a small laboratory set up in his office building. In the archives of the Parisian police are reports of cases that he solved by applying forensic methods decades before they were recognized as such.

- Chemical compounds

- In the France of Vidocq's time, there already existed cheques and promissory notes. Counterfeiters purchased those cheques and altered them to their advantage. In 1817, Vidocq addressed this problem by commissioning two chemists to develop a tamper-proof paper. This paper, for which Vidocq filed a patent, was treated with chemicals that would smear the ink if later amended and thus make the forgeries identifiable. According to the biographer Edwards, Vidocq used his connections extensively, recommending his paper to those who had been deceived, mainly bankers who hired him. Therefore, the paper came to be widely used. Vidocq also used it for the cards of his index card system to emphasize their reliability in court. He also commissioned the creation of indelible ink. This ink has been used, among other things, by the French government for the printing of banknotes from the mid-1860s.

- Crime scene investigation

- Louis Mathurin Moreau-Christophe, contemporary general director of French prisons, described in his book Le monde des coquins (The World of Scoundrels) how Vidocq used clues from the crime scene to determine the perpetrator based on his knowledge of specific criminals and their modus operandi. As a concrete example, Moreau named a burglary in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in 1831, where he himself had been present at the investigation. Vidocq inspected a door panel that had been damaged by the offender and said that, due to the method employed and the perfection with which it had been executed, he knew of only one perpetrator who could have done it. He suggested the thief Fossard but mentioned that he could not be the culprit, since he was still in prison. The police chief, Lecrosnier, who was also present, told them that Fossard had escaped eight days before. Two days later, Vidocq arrested Fossard, who had in fact committed the burglary.

- Ballistics

- Alexandre Dumas left records that describe a murder case from 1822. The Comtesse Isabelle d'Arcy, a woman much younger than her husband on whom she had cheated, was shot dead, whereupon the police arrested the Comte d'Arcy. Vidocq talked with him and was of the opinion that the "old gentleman" did not have the personality of a murderer. He examined his dueling pistols and found that they either had not been fired or had been cleaned since then. Then he persuaded a doctor to remove the bullet from the head of the noblewoman secretly. A simple comparison showed that the bullet was too big to come from the guns of the Comte. Vidocq then searched the apartment of the woman's lover and found not only numerous pieces of jewellery, but also a large pistol whose size fit the bullet. The Comte identified the jewels as those of his wife and Vidocq also found a fence to whom the lover had already sold a ring. Confronted with the evidence, the lover confessed to the murder.

The first real comparison between a gun and a bullet took place in 1835 by the Bow Street Runner Henry Goddard. On 21 December 1860, The Times reported on a court ruling in which a murderer in Lincoln named Thomas Richardson had been convicted with the help of ballistics for the first time.

The Vidocq Society[edit]

In 1990, the Vidocq Society was founded in Philadelphia by forensic artist/sculptor Frank Bender (d. 2011). Its members are forensic experts, FBI profilers, homicide investigators, scientists, psychologists, coroners, and any other competent professionals. At their monthly meetings, they try to solve cold cases from around the world, free of charge and in accordance with their motto Veritas veritatum ("Truth generates truth"). The rolls of membership are closed and the number of members remains low enough to never exceed the number of years of Vidocq's life.

Depictions of Vidocq[edit]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

Literature[edit]

In 1829, two journalists under the pseudonym of a criminal named Malgaret published the book Mémoires d'un forçat ou Vidocq dévoilé to expose criminal activities Vidocq allegedly had committed. Other police officers followed the example of Vidocq's memoirs and published their own autobiographies in the following years, among them the prefect of police, Henri Gisquet.

Vidocq's life story inspired many contemporary writers, many of them his closest friends. In Balzac's writings, he was regularly the model of literary figures: his experiences as a failed entrepreneur were used in the third part of Illusions perdues, "Les Souffrances de l'inventeur"; in Gobseck, Balzac introduced the policeman Corentin; but most clearly, the connection to Vidocq can be found in the figure of Vautrin. This character first appears in the novel Le Père Goriot, then in Illusions perdues, Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes (as the main character), La Cousine Bette, Le Contrat de mariage, and finally as the main character in the 1840 theatre play Vautrin. Not only Vidocq as a person but also his methods and disguises inspired Balzac in his work.

In Victor Hugo's Les Misérables (1862), both main characters, the reformed criminal Jean Valjean and Police Inspector Javert, were modeled after Vidocq, as was the policeman Monsieur Jackal in The Mohicans of Paris (1854–1855) by Alexandre Dumas.[citation needed] He also was the basis for Rodolphe de Gerolstein, who secured justice in the serial newspaper novel The Mysteries of Paris of Eugène Sue in the weekly newspaper Journal des débats; and he was the inspiration of Émile Gaboriau for Monsieur Lecoq, one of the first scientific and methodical investigators who played the lead role in many adventures, who in turn was a major influence for the creation of Sherlock Holmes.[citation needed] It is also believed that Edgar Allan Poe was prompted by a story about Vidocq to create the first detective in fiction, C. Auguste Dupin,[15] who appeared, for example, in the short story "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", which is considered the first detective story.[16][17][18] Vidocq is also mentioned in Moby Dick ("Chapter 88: Schools and Schoolmasters") and White Jacket ("Chapter VI: The Quarterdeck Officers, etc.") by Herman Melville[19] and Great Expectations by Charles Dickens.

In the Sandman Slim series of urban fantasy books by Richard Kadrey, a fictionalized version of Vidocq is a friend and mentor to the protagonist James Stark. Kadrey's Vidocq has become immortal thanks to an alchemical accident and lives in modern-day Los Angeles.[20]

Another contemporary novel that features Vidocq is Louis Bayard's The Black Tower (2008), though it is set in Restoration France.

Vidocq also appears as a major character in James McGee's novel Rebellion (2011)

Vidocq is frequently alluded to in Burt Solomon's 2017 novel The Murder of Willie Lincoln.

Theatre[edit]

Vidocq was a friend of the theater. During his lifetime, the Boulevard du Crime, a road with several theatres that regularly presented crime stories in the form of melodramas, was quite popular. One of these theatres was the Théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique, which was sponsored by Vidocq to a great extent. According to the biographer James Morton, Vidocq also submitted a play, but it was never produced. He also had plans to dabble in play acting but never carried them out.

Not only were many of Vidocq's paramours actresses, but many of his friends and acquaintances were also from the theatre scene. Among them was the famous actor Frédérick Lemaître, who among other things played the main role in Balzac's Vautrin, a play which debuted on 14 March 1840 at Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin after numerous problems with censorship. Lemaître tried to adapt his appearance to that of Vidocq, on whom the character Vautrin was based. At the premiere, there were commotions because the wig Lemaître had used was also similar to the one of King Louis-Philippe. The play was banned by the French interior minister after that and not performed again.

It was not only plays inspired by Vidocq that were shown in the theatre. His one life story also made it on stage several times, usually with his memoirs as a literary template. Especially in England, there was great enthusiasm for Vidocq. The memoirs had been rapidly translated into English, and a few months later, on 6 July 1829, the premiere of Vidocq! The French Police Spy was held at Surrey Theatre in the London Borough of Lambeth. The melodrama in two acts, produced by Robert William Elliston, was penned by Douglas William Jerrold, and the main character was played by TP Cooke. Although the critics, among them one from The Times, were quite positive, the play was performed only nine times in the first month and then dropped.

In December 1860, some years after Vidocq's death, another play about him, written by F. Marchant, was presented in Britannia Theatre in Hoxton under the title Vidocq or The French Jonathan Wild. It was included in the theatre program for only one week.

In 1909, Émile Bergerat wrote the melodrama Vidocq, empereur des policiers in five acts and seven scenes. The producers Hertz and Coquelin rejected it, but Bergerat sued them successfully for 8,000 francs in damages. The play debuted in 1910 in Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt. Jean Kemm, who years later would also participate in a movie about Vidocq, took over the lead role.

Film[edit]

A film based on Vidocq's memoirs was released in France on 13 August 1909, a short black-and-white silent film La Jeunesse de Vidocq ou Comment on devient policier. Vidocq was played by Harry Baur, who also portrayed him in two sequels: L'Évasion de Vidocq (1910) and Vidocq (1911). Under the direction of Jean Kemm, the silent movie Vidocq based on the memoirs appeared in 1922. The screenplay was written by Arthur Bernède and the main role was played by René Navarre. The first sound film, again entitled Vidocq, appeared in 1939. Jacques Daroy directed André Brulé in the title role. The film focused largely on Vidocq's criminal career.

On 19 July 1946, the first American film about Vidocq appeared – A Scandal in Paris, with George Sanders as Vidocq and direction by Douglas Sirk. It showed the rise of a rogue in society, coupled with a love story. It was followed in April 1948 by the next French version of Vidocq's life story, Le Cavalier de Croix-Mort, directed by Lucien Ganier-Raymond with Henri Nassiet in the lead.

On 7 January 1967, the French television station ORTF showed the first of two television series, each with thirteen episodes. Vidocq starring Bernard Noël was still in black and white. The second series, Les Nouvelles Aventures de Vidocq, the first in color, premiered on 5 January 1971 and starred Claude Brasseur.

In 1989, the pilot episode "Trail" was devoted to Eugène Vidocq. The series was called Adventure of Criminalistics and was filmed in a Czechoslovakian–German co-production.

In 2001, under the direction of Pitof, Gérard Depardieu played Vidocq in the French science fiction film Vidocq.

In 2018, Jean-Francois Richet directed a film with Vincent Cassel as Vidocq, The Emperor of Paris (L'Empereur de Paris).[21][22]

Comics[edit]

Vidocq's life inspired a comics series by Dutch artist Hans G. Kresse, which was published in the magazine Pep between 1965 and 1969. It was a realistic adventure series set during the Napoleonic era, where Vidocq is portrayed as a detective with a criminal past.[23]

Video games[edit]

Assassin's Creed Unity takes place during the French Revolution, and features a series of side missions based on investigating murders in Paris. While Arno, the main character, takes his assignments from the dozing chief of police, a youthful Vidocq can be found in the adjacent jail cell offering advice while pleading to be let out to help Arno solve cases.

Vidocq appears as a playable character in the adventure mystery game Inspector Javert and the Oath of Blood.[24][25]

Writings[edit]

Around 1827, Vidocq wrote an autobiography, which he planned for the bookseller Émile Morice to publish in summer 1828. Honoré de Balzac, Victor Hugo, and Alexandre Dumas thought that the story was too short. So Vidocq found a new publisher, Louis-François L'Héritier. In December 1828, L'Héritier published the memoirs, which had grown to four volumes through the help of some ghostwriters. The work became a bestseller and sold over 50,000 copies in the first year.[26]

- Mémoires de Vidocq, chef de la police de Sûreté, jusqu'en 1827, ghost-written autobiography, 1828

- Memoirs of Vidocq in English Vol III

- Memoirs of Vidocq in English Vol IV

- Les voleurs, a study of thieves and imposters, 1836, Roy-Terry, Paris

- Dictionnaire d'Argot, a dictionary of argot, 1836

- Considérations sommaires sur les prisons, les bagnes et la peine de mort, deliberations on reducing crime, 1844

- Les chauffeurs du nord, a memoir of his time as a gang member, 1845

- Les vrais mystères de Paris, a novel published under Vidocq's name, though authored by Horace Raisson and Maurice Alhoy, 1844

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Siegel, Jay A.: Forensic Science: The Basics. CRC Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8493-2132-8, S. 12.

- ^ a b Conser, James Andrew and Russell, Gregory D.: Law Enforcement in the United States. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2005, ISBN 0-7637-8352-8, S. 39.

- ^ Emsley, Clive and Shpayer-Makov, Haia: Police Detectives in History, 1750–1950. Ashgate Publishing, 2006, ISBN 0-7546-3948-7, S. 3.

- ^ Hügel, Hans-Otto: Untersuchungsrichter, Diebsfänger, Detektive. Metzler, 1978, ISBN 3-476-00383-3, S. 17.

- ^ https://www.arras.fr/en/node/11669 Ville d'Arras municipal information

- ^ a b c Memoirs of Vidocq: Principal Agent of the French Police Until 1827. Carey, 1834

- ^ Metzner, Paul: Crescendo of the Virtuoso. Spectacle, skill and self-promotion in Paris during the age of revolution

- ^ a b c James Morton: The First Detective: The Life and Revolutionary Times of Vidocq: Criminal, Spy and Private Eye

- ^ Savant, Jean: La vie aventureuse de Vidocq. Librairie Hachette, Paris 1973, p. 299.

- ^ Stead, John Philip: Vidocq: A Biography.. 4th edition, Staples Press, London, January 1954, p. 247

- ^ Time.com: Finest of the Finest

- ^ Parker, Alfred Eustace. The Berkeley Police Story. Charles C Thomas Pub, 1972, ISBN 0-398-02373-5, p. 53.

- ^ Theoharis, Athan G. The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Greenwood Press, 1999, ISBN 0-89774-991-X, p. 265f.

- ^ Coe, Ada. The Detective: A Myth for Our Time. University of California, Davis Press, 2000, p. 10.

- ^ Cornelius, Kay. Biography of Edgar Allan Poe in Bloom's BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe, Harold Bloom, ed. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2001. p. 31 ISBN 0-7910-6173-6

- ^ Silverman, Kenneth (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance (Paperback ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. pp. 171. ISBN 0-06-092331-8.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (1992). Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York: Cooper Square Press, 123. ISBN 0-8154-1038-7

- ^ Rzepka, Charles J. Detective Fiction. chapter 3 – From Rogues to Ratiocination

- ^ Melville, Hermann. Schools and Schoolmasters

- ^ "Author Interview: Richard Kadrey of Sandman Slim". Nerdlocker. 28 July 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ "Gaumont Boards J.F. Richet-Vincent Cassel Pic 'The Emperor of Paris'". 26 September 2017.

- ^ "The Emperor of Paris (2018)". IMDb.

- ^ "Hans G. Kresse".

- ^ "Inspector Javert and the Oath of Blood". IGDB.com. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- ^ "About". INSPECTOR JAVERT AND THE OATH OF BLOOD | PC GAME. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- ^ Samuel Edwards....[clarification needed]

Bibliography[edit]

Biographies[edit]

English[edit]

- Edwards, Samuel (1977). The Vidocq Dossier: The Story of the World's First Detective (1st ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-25176-1.

- Hodgetts, Edward A. (1928). Vidocq: A Master of Crime. London: Selwyn & Blount.

- Morton, James (2004). The First Detective: The Life and Revolutionary Times of Vidocq. Ebury Press. ISBN 978-0-09-190337-4.

- Stead, John Philip (1954). Vidocq: Picaroon of Crime.

French[edit]

- Guyon, Louis (1826). Biographie des Commissaires et des Officiers de Paix de la ville de Paris (Goullet ed.). Paris.

- Maurice, Barthélemy (1861). Vidocq. Vie et aventures. Paris: Laisné.

- Savant, Jean (1973). La vie aventureuse de Vidocq. Paris: Librairie Hachette.

Influence on criminalistics[edit]

- Emsley, Clive; Shpayer-Makov, Haia (2006), Police detectives in history, 1750–1950 (in German), Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate, ISBN 0-7546-3948-7

- Feix, Gerhard (1979). Das große Ohr von Paris. Fälle der Sûreté. Berlin: Verlag Das Neue Berlin.

- Kalifa, Dominique (2000). Naissance de la police privée : détectives et agences de recherches en France, 1832 - 1942. [Paris]: Plon. ISBN 2-259-18291-7.

- Metzner, Paul (1998). Crescendo of the virtuoso : spectacle, skill and self-promotion in Paris during the age of revolution. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20684-3.

- Thorwald, Jürgen (1981). Das Jahrhundert der Detektive (1. - 25. Tsd. ed.). Zürich: Droemer-Knauer. ISBN 3-85886-092-1. (earlier title: Das Jahrhundert der Detektive).

Influence on literature[edit]

- Rix, Paul G. Buchloh, Jens P. Becker. Mit Beitr. von Antje Wulff u. Walter T. (1973). Der Detektivroman, Studien z. Geschichte u. Form d. engl. u. amerikan. Detektivliteratur (2nd revised and enlarged ed.). Darmstadt: Wissenshaftliche Buchgesellshaft. ISBN 3-534-05379-6.

- Engelhardt, von Sandra (2003). The investigators of crime in literature. Marburg: Tectum-Verlag. ISBN 3-8288-8560-8.

- Messac, Régis (1975). Le "detective novel" et l'influence de la pensée scientifique. Geneva: Slatkine. (Reprint of the Paris edition of 1929).

- Murch, Alma E. (1968). The development of the detective novel. London: P. Owen.

- Rzepka, Charles J. (2005). Detective fiction (Repr. ed.). Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 0-7456-2941-5.

- Schwarz, von Ellen (2001). Der phantastische Kriminalroman : Untersuchungen zu Parallelen zwischen roman policier, conte fantastique und gothic novel. Marburg: Tectum-Verlag. ISBN 3-8288-8245-5. (also thesis, Universität Giessen 2001).

- Symons, Julian (1994). Bloody murder : from the detective story to the crime novel : a history ([4th ed.]. ed.). London: Pan. ISBN 0-330-33303-8.

External links[edit]

- Vidocq – Du Bagne à la Police de Sûreté (French)

- Works by Eugène François Vidocq at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Eugène François Vidocq at Internet Archive

- Works by Eugène François Vidocq at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Appraisal by Vidocq's hometown Arras (French)

- Vidocq in CrimeLibrary

- Vidocq Society

- Vidocq – Defrosting Cold Cases