اَردا ویراف نامه یا اَردا ویراز نامه نام یکی از کتابهای نوشتهشده به زبان پارسی میانه است که از پیش از اسلام به جا ماندهاست. مضمون کتاب، اعتقادات عامه ایرانیان پیش از اسلام درباره آخرت است.[۱]

ویراف مقدس، نام یکی از موبدان که به عقیده پارسیان صاحب معراج بوده و ارداویرافنامه معراجنامه اوست. داستان دینی ارداویراف همانندی زیادی با کمدی الهی دانته دارد و پژوهشگران بر این باورند که دانته در آفریدن اثر خود از منابع عربی یاری گرفته و آن منابع به نوبه خود از ارداویرافنامه اقتباس کردهاند.

کتاب معروف ارداویرافنامه تصویر جامعی از دوزخ در زرتشتیگری به دست میدهد. این کتاب که ظاهرأ در قرن سوم هجری به رشتهٔ تحریر درآمدهاست، یکی از منابع مهم تاریخ شفاهی آیین باستانی زرتشتی است. از محتوای کتاب چنین برمیآید که متن اصلی پهلوی آن به اواخر دورهٔ ساسانی تعلق داشتهاست. کتاب داستان موبدی است که برای بیگمان شدنِ مردمان درباره دین و رستاخیز و بهشت و دوزخ، خویش را به یاری موبدان دیگر به خواب هفتروزه میبرد و روان او در بهشت، نیکیهای نیکوکاران و در دوزخ باداَفرَه (: مجازات) بدکاران را میبیند و پس از به هوش آمدن آن داستانها را بازمیگوید. این مرد ویراف نام دارد که او را اردا به معنای قدیس لقب دادهاند. ارداویراف را موبدان آیین مزدیسنی شربتی مخدر و مقدس میخورانند که تحت تأثیر آن وی به مدت سه شبانهروز به خواب میرود و پس از بیداری داستان سیروسلوک روحی خود را برای دیگران بازگو میکند. گرچه قصهٔ سیروسلوک روحی ارداویراف جنبهٔ موهومی دارد، باز منبعی بینظیر از برداشتی که زرتشتیان از بهشت و جهنم داشتهاند به ما ارائه میدهد.

...

داریوش کارگر ارداویرافنامه را «براساس شش دستنوشته و مقایسه با روایت و نسخه زبان پهلوی و ترجمه انگلیسی» تصحیح کرد و «کاملترین نسخه» این متن کهن را به دست داد.

این کتاب را دانشگاه اوپسالا با عنوان اردایویرافنامه، روایت فارسی زرتشتی منتشر کرده است.

محتویات

[نهفتن]داستان[ویرایش]

در دیباچه ترجمه کهن ارداویرافنامه به پارسی چنین آمدهاست: ایدون گویند که چون شاه اردشیر بابکان به پادشاهی بنشست، نود پادشاه بکشت و بعضی گویند نودوشش پادشاه بکشت و جهان را از دشمنان خالی کرد و آرمیده گردانید و دستوران و موبدانی که در آن زمان بودند همه را پیش خویشتن خواند و گفت که دین راست و درست که ایزدتعالی به زرتشت... گفت و زرتشت در گیتی روا کرد مرا بازنمایید، تا من این کیشها و گفتوگویها از جهان برکنم و اعتقاد با یکی آورم، و کس بفرستاد به همه ولایتها، هر جایگاه که دانایی و یا دستوری بود همه را به درگاه خود خواند. چهلهزار مرد بر درگاه انبوه شد. پس بفرمود و گفت آنهایی که از این داناترند باز پلینند. چهارهزار داناتر از آن جمله گزیدند و شاهانشاه را خبر کردند و گفت دیگر بار احتیاط بکنید. دیگر نوبت از آن جمله قومی که به تمیز و عقل و افستا و زند بیشتر از بر دارند جدا کنید. چهارصد مرد برآمد که ایشان افستا و زند بیشتر از بر داشتند. دیگرباره احتیاط کردند در میان ایشان چهل مرد بگزیدند که ایشان افستاجمله از بر داشتند. دیگر در میان آن جملگی هفت مرد بودند که از اول عمر تا به آن روزگار که ایشان رسیده بودند بر ایشان هیچ گناه پیدا نیامده بود و بهغایت عظیم پهریخته بودند و پاکیزه در منشن و گُوشن و کُنشن و دل در ایزد بسته بودند. بعد از آن هر هفت را به نزدیک شاه اردشیر بردند. بعد از آن شاه فرمود که مرا میباید که این شک و گمان از دین برخیزد و مردمان همه بر دین اورمزد و زرتشت باشند و گفتوگوی از دین برخیزد، چنانکه مرا و همه عالمان و دانایان را روشن شود که دین کدام است و این شک و گمان از دین بیفتد.

بعد از آن ایشان پاسخ دادند که کسی این خبر باز نتواند دادن الا آن کسی که از اول عمر هشتسالگی تا بدان وقت که رسیده باشد هیچ گناه نکرده باشد و این مرد ویراف است که از او پاکیزهتر و مینوروشنتر و راستگوی تر کس نیست و این قصه اختیار بر وی باید کردن و ما ششگانه دیگر یزشنها و نیرنگها که در دین ازبهر این کار گفتهاست به جای آوریم تا ایزد عز و جل احوالها به ویراف نماید و ویراف ما را از آن خبر دهد تا همه کس به دین اورمزد و زرتشت بیگمان شوند و ویراف این کار در خویشتن پذیرفت و شاه اردشیر را آن سخن خوش آمد و پس گفتند این کار راست نگردد مگر که به درگاه آذران شوند و پس برخاستند و عزم کردند و برفتند و پس از آن، آن شش مرد که دستوران بودند از یک سویِ آتشگاه یزشنها بساختند و آن چهل دیگر سویها با چهلهزار مرد دستوران که به درگاه آمده بودند همه یزشنها بساختند و ویراف سر و تن بشست و جامه سفید درپوشید و بوی خوش بر خویشتن کرد و پیش آتش بیستد و از همه گناهها پتفت بکرد... پس شاهنشاه اردشیر با سواران سلاح پوشیده، گِرد بر گِرد آتشگاه نگاه میداشت تا نه که آشموغی یا منافقی پنهان چیزی بر ویراف نکنند که او را خللی رسد و چیزی بدی در میان یزشن کند که آن نیرنگ باطل شود.

پس در میان آتشگاه تختی بنهادند و جامههای پاکیزه برافکندند و ویراف را بر آن تخت نشاندند و رویبند بر وی فروگذاشتند و آن چهلهزار مرد بر یزشن کردن ایستادند و درونی بیشتند و قدری په بر آن درون نهادند. چون تمام بیشتند یک قدح شراب به ویراف دادند و... هفت شبانروز ایشان بهمجا یزشن میکردند و آن شش دستور به بالین ویراف نشسته بود سی و سه مرد دیگر که بهگزیده بودند از گرد بر گرد تخت یزشن میکردند و آن تیرست و شصت مرد که پیشتر بهگزیده بودند از آن گرد بر گرد ایشان یزشن میکردند و آن سی و شش هزار گرد برگرد آتشگاه گنبد یزشن میکردند و شاهنشاه سلاح پوشیده و بر اسب نشسته با سپاه از بیرون گنبد میگردید. باد را آنجا راه نمیدادند و به هر جایی که این یزشنکنان نشسته بودند بهر قومی جماعتی شمشیر کشیده و سلاح پوشیده ایستاده بودند تا گروهها بر جایگاه خویشتن باشند و هیچ کس بدان دیگر نیامیزند و آن جایگاه که تخت ویراف بوداز گرد بر گرد تخت پیادگان با سلاح ایستاده بودند و هیچ کس دیگر را بهجز آن شش دستور نزدیک تخت رها نمیکردند. چو شاهنشاه درآمدی از آنجا بیرون آمدی و گرد بر گرد آتشگاه نگاه میداشتی. و بر این سختی کالبد ویراف نگاه میداشتی. یشتند تا هفت شبانروز برآمد. بعد از هفت شبانروز ویراف بازجنبید و باززیید و بازنشست و مردمان و دستوران چون بدیدند که ویراف از خواب درآمد خرمی کردند و شاد شدند و رامش پذیرفتند و بر پای ایستادند و نماز بردند و گفتند: شادآمدی اردایویراف... چگونه آمدی و چون رستی و چه دیدی؟ ما را بازگوی تا ما نیز احوال آن جهان بدانیم... ارداویراف واج گرفت، چیزی اندک مایه بخورد و واج بگفت. پس بگفت این زمان دبیری دانا را بیاورید تا هرچه من دیدهام بگویم و نخست آن در جهان بفرستید تا همه کس را کار مینو و بهشت و دوزخ آشکار شود و قیمت نیکی کردن بدانند و از بد کردن دور باشند. پس دبیری دانا بیاوردند و در پیش ارداویراف بنشست.

در ادبیات معاصر[ویرایش]

گزارش ارداویراف نمایشنامهای از بهرام بیضایی است که براساس ارداویرافنامه نوشته شده و در ژانویه ۲۰۱۵ در دانشگاه استنفورد دو شب پیاپی با کارگردانی نویسنده بر صحنه برای تماشاگران خوانده شده.[۲]

مشخصات نشر[ویرایش]

- آموزگار، ژاله و ژینیو، فیلیپ ، ارداویرافنامه (ارداویرازنامه)/ حرفنویسی، آوانویسی، ترجمه متن پهلوی، انتشارات معین و انجمن ایرانشناسی فرانسه، تهران، چاپ اول: 1372، چاپ دوم، 1382.

پیوند به بیرون[ویرایش]

- Ardā Virāz Nāmag - Titus، متن کامل کتاب

- ترجمه انگلیسی ارداویرافنامه

منابع[ویرایش]

- ↑ «ارداویرافنامه»، نوشته رشید یاسمی، مجله مهر، خرداد ۱۳۱۴

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/persian/arts/2015/01/150127_l51_beizaee_ardaviraf_play

- لغتنامه دهخدا

- ارداویرافنامه در یادنامه پورداود ج ۱

///////////////

کمدی الهی سهگانهایست به شعر که دانته آلیگیری، شاعر و نویسنده ایتالیایی نوشتن آنرا در سال ۱۳۰۸ میلادی آغاز کرد و تا زمان مرگش در سال ۱۳۲۱ میلادی کامل کرد. این کتاب از زبان اول شخص است و دانته در این کتاب، سفر خیالی خود را به دوزخ،برزخ و بهشت تعریف میکند. کمدی الهی یکی از اولین کتابهای ادبیات ایتالیا است و از بزرگترین آثار در ادبیات جهان به شمار میآید. این کتاب کمک کرد تا زبان توسکانی و شیوهٔ نوشتاری آن به استانداردی برای زبان ایتالیایی تبدیل شود.[۱]

این کتاب در ابتدا کمدی (به ایتالیایی: Commedìa) نام داشت و بعدها جیووانی بوکاچیو (نویسنده هم عصر دانته) واژهٔ الهی را به آن افزود و نام کمدی الهی برای اولین بار در چاپ ونیز به سال ۱۵۵۵ بر جلد این کتاب ظاهر شد.[۱]

در سفر دانته به دنیای پس از مرگ، دو راهنما او را همراهی میکنند؛ در دوزخ و برزخ راهنمای او «ویرژیل»، شاعر رومی است که چند قرن پیش از دانته زندگی میکرده، و در بهشت راهنمای او بئاتریس پورتیناری است که دانته او را دوست میداشته و در کتاب زندگانی نو به شرح عشق خود به او پرداختهاست.

دانته در این کتاب از مراحل مختلف دوزخ، برزخ و بهشت میگذرد و در این مراحل با شخصیتهای مختلف تاریخی برخورد میکند، تا عاقبت در آخرین مرحله بهشت به دیدار خدا میرسد.

محتویات

[نهفتن]کمدی الهی در ادبیات فارسی[ویرایش]

شجاعالدین شفا اولین مترجم فارسی این اثر بزرگ به زبان فارسی، (چاپ نخست سال ۱۳۳۵ انتشارات امیرکبیر) در مقدمهای مبسوط به بررسی کمدی الهی، زندگی و آثار دانته، نقش و تأثیر کمدی الهی بر ادبیات جهان پس از خود، پرداخته است. کمدی الهی پس از انقلاب دیگر تجدید چاپ نشد، تا سالها نایاب بود تا اینکه سرانجام دوباره از وزارت ارشاد مجوز نشر گرفت اما در آغاز آن توضیحی اضافه شد مبنی بر اینکه شجاعالدین شفا، از «معاندین» انقلاب بوده و چاپ این کتاب دلیلی بر توجیه و تأیید شخصیت مترجم نیست.[نیازمند منبع]

طی دهههای اخیر، برخی این اثر را با ارداویرافنامه که در اواخر دورهٔ ساسانیان به زبان و خط پهلوی نوشته شده مقایسه کردهاند.[نیازمند منبع] ارداویرافنامه حدود هزار سال پیش از کمدی الهی به سفر به دنیای پس از مرگ میپردازد. در ایران، در دو اثر باستانی دیگر غیر از ارداویرافنامه، موضوع سفر به دنیای پس از مرگ را ثبت کردهاند: کتیبه کرتیر در سرمشهد متعلق به دوران ساسانیان و دیگری در افسانه ویشتاسب یا گشتاسبشاه.

طی دهههای اخیر، برخی این اثر را با ارداویرافنامه که در اواخر دورهٔ ساسانیان به زبان و خط پهلوی نوشته شده مقایسه کردهاند.[نیازمند منبع] ارداویرافنامه حدود هزار سال پیش از کمدی الهی به سفر به دنیای پس از مرگ میپردازد. در ایران، در دو اثر باستانی دیگر غیر از ارداویرافنامه، موضوع سفر به دنیای پس از مرگ را ثبت کردهاند: کتیبه کرتیر در سرمشهد متعلق به دوران ساسانیان و دیگری در افسانه ویشتاسب یا گشتاسبشاه.

ساختار[ویرایش]

این منظومه بلند، متشکل از سه بخش دوزخ، برزخ و بهشت است و هر بخشی سیوسه چکامه (کانتو) دارد که به اضافه مقدمه، در مجموع شامل صد چکامه میشود. در کتاب مذکور آمدهاست: دانته برای این اثر از قافیهپردازی جدیدی که به «قافیه سوم» مشهور شد، سود جست. هر چکامه به بندهای «سه بیتی» تقسیم میشود که بیت اول و سوم، هم قافیهاند و بیت میانی با بیت اول و سوم بند بعدی، دارای قافیه جداگانهاست. مبنای وزن هر بیت یازده هجایی است. مجموع ابیات کمدی الهی به ۱۲۲۳۳ بیت میرسد. زبان این اثر گویش ایالت توسکانا است که در تثبیت آن به عنوان گویش برتر زبان ایتالیایی و مبنای زبان ایتالیایی جدید مؤثر بودهاست.

آثار هنری مرتبط[ویرایش]

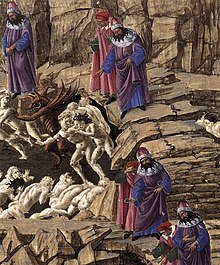

شاعران، نقاشان و مجسمهسازان بزرگ بسیاری به خلق آثار برجستهای پرداختند که موضوع اصلی آن صحنهها و داستانهای کمدی الهی است. بوتیچلی، نقاش بزرگ و معاصر میکل آنژ در سدهٔ ۱۵ (میلادی)، یکی از آنان است. دلاکروا، نقاش بزرگ دیگر و ویلیام بلیک شاعر بزرگ انگلیسی سدهٔ ۱۸ (میلادی)، گوستاو دوره، نقاش و حجار بزرگسدهٔ ۱۹ (میلادی)، رافائل، شفر، گلز، دلابرد، هامان، مورانی و بسیاری دیگر، از زمره کسانی هستند که با موضوع کمدی الهی آثار جاودانی خلق کردهاند. بجز اینها از دیر باز تا کنون در کرسیهای «دانته شناسی» در دانشگاههای معتبر جهان، به شناخت، تفسیر و معرفی کمدی الهی میپردازند.اخیراً هم نویسندهٔ آمریکایی دن براون کتابی تحت عنوان دوزخ منتشر کرده که الهام گرفته از کمدی الهی دانته است

جستارهای وابسته[ویرایش]

- گوستاو دوره - نقاش فرانسوی که طراحیهای او برای کمدی الهی بسیار مشهوراند.

- ارداویرافنامه - یکی از کتابهای نوشته شده به زبان پارسی میانه که به اعتقادات عامه ایرانیان پیش از اسلام دربارهٔ آخرت میپردازد.

منابع[ویرایش]

| در ویکیانبار پروندههایی دربارهٔکمدی الهی موجود است. |

- ↑ ۱٫۰ ۱٫۱ مشارکتکنندگان ویکیپدیا، «Divine Comedy»، ویکیپدیای انگلیسی، دانشنامهٔ آزاد (بازیابی در ۱۸ شهریور ۱۳۹۳).

پیوند به بیرون[ویرایش]

- دانلود رایگان نسخههای دوزبانه (متن اصلی ایتالیایی و برگردان انگلیسی) سه جلد کمدی الهی (دوزخ، برزخ و بهشت) از تارنمای کتابخانهٔ آنلاین آزادی

- دانلود رایگان نسخهٔ فارسی سه جلد کمدی الهی (دوزخ، برزخ و بهشت) در سایت بهترین کتابهای جهان

//////////////

The Book of Arda Viraf[pronunciation?] is a Zoroastrian religious text of Sassanid era in Middle Persian language that contains about 8,800 words.[1] It describes the dream-journey of a devout Zoroastrian (the 'Viraf' of the story) through the next world. Due to the ambiguity inherent to Pahlavi script, 'Viraf' (the name of the protagonist) may also be transliterated as 'Wiraf', 'Wiraz' or 'Viraz'.[2] The 'Arda' of the name (cf. Asha; cognate with Skt. r̥ta) is an epithet of Viraf and is approximately translatable as "truthful" or "righteous." "Viraz" is probably akin to Proto-Indo-European *wiHro--, "man" see Skt. vīra. The text assumed its definitive form in the 9th-10th centuries A.D., after a long series of emendations.[3]

Contents

[show]Textual History[edit]

The date of the book is not known, but in The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East, Prof. Charles Horne assumes that it was composed fairly late in the ancient history of Zoroastrianism, probably from the period of the Sassanian empire, when Zoroastrianism experienced a state-sponsored revival.[4] The fact that the "evil" Alexander the Great is referred to as a Roman suggests this period[citation needed], in which the rivalry between the two empires was intense.

Plot summary[edit]

Arda Viraf is chosen for his piety to undertake a journey to the next world in order to prove the truth of Zoroastrian beliefs, after a period when the land of Iran had been troubled by the presence of confused and alien religions. He drinks wine and a hallucinogen, after which his soul travels to the next world where it is greeted by a beautiful woman named Den who represents his faith and virtue. Crossing the Chinvat bridge, he is then conducted by "Srosh, the pious and Adar, the angel" through the "star track", "moon track" and "sun track" – places outside of heaven reserved for the virtuous who have nevertheless failed to conform toZoroastrian rules. In heaven, Viraf meets Ahura Mazda who shows him the souls of the blessed (ahlav). Each person is described living an idealised version of the life he or she lived on earth, as a warrior, agriculturalist, shepherd or other profession.[5] With his guides he then descends into hell to be shown the sufferings of the wicked. Having completed his visionary journey Viraf is told by Ahura Mazda that the Zoroastrian faith is the only proper and true way of life and that it should be preserved in both prosperity and adversity.[5]

Quotes from the Text[edit]

- They say that, once upon a time, the pious Zartosht made the religion, which he had received, current in the world; and till the completion of 300 years, the religion was in purity, and men were without doubts. But afterward, the accursed evil spirit, the wicked one, in order to make men doubtful of this religion, instigated the accursed Alexander, the Rûman,[6] who was dwelling in Egypt, so that he came to the country of Iran with severe cruelty and war and devastation; he also slew the ruler of Iran, and destroyed the metropolis and empire, and made them desolate.[7]

- Introduction

- Then I saw the souls of those whom serpents sting and ever devour their tongues.And I asked thus: 'What sin was committed by those, whose soul suffers so severe a punishment?' Srosh the pious, and Adar the angel, said, thus: 'These are the souls of those liars and irreverent [or 'untruthful'] speakers who, in the world, spoke much falsehood and lies and profanity.[7]

- Section 4, Hell

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ http://www.farvardyn.com/pahlavi4.php#57

- ^ http://titus.uni-frankfurt.de/texte/etcs/iran/miran/mpers/arda/arda.htm

- ^ Philippe Gignoux, "Ardā Wīrāz", Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, New York, 1996-, consulted 21 February 2015. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/arda-wiraz-wiraz

- ^ https://archive.org/stream/sacredbooksearly07hornuoft

- ^ a b http://www.avesta.org/pahlavi/viraf.html Translation of the Book of Arda Viraf

- ^ Alexander the Great was called "the Ruman" in Zoroastrian tradition because he came from Greek provinces which later were a part of the eastern Roman empire - The archeology of world religions By Jack Finegan Page 80 ISBN 0-415-22155-2

- ^ a b http://www.avesta.org/mp/viraf.html

///////////////

The Divine Comedy (Italian: Divina Commedia [diˈviːna komˈmɛːdja]) is an epic poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed 1320, a year before his death in 1321. It is widely considered the preeminent work of Italian literature[1] and is seen as one of the greatest works of world literature.[2]The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval world-view as it had developed in the Western Church by the 14th century. It helped establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language.[3] It is divided into three parts: Inferno,Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

On the surface, the poem describes Dante's travels through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise orHeaven;[4] but at a deeper level, it represents, allegorically, the soul's journey towards God.[5] At this deeper level, Dante draws on medieval Christian theology and philosophy, especially Thomistic philosophy and the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas.[6] Consequently, the Divine Comedy has been called "the Summa in verse".[7]

The work was originally simply titled Comedìa and the word Divina was added by Giovanni Boccaccio. The first printed edition to add the word divina to the title was that of the Venetian humanist Lodovico Dolce,[8] published in 1555 by Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari.

Contents

[show]Structure and story[edit]

The Divine Comedy is composed of 14,233 lines that are divided into three canticas (Italian plural cantiche) –Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Paradise) – each consisting of 33 cantos (Italian plural canti). An initial canto, serving as an introduction to the poem and generally considered to be part of the first cantica, brings the total number of cantos to 100. It is generally accepted, however, that the first two cantos serve as a unitary prologue to the entire epic, and that the opening two cantos of each cantica serve as prologues to each of the three cantiche.[9][10][11]

The number three is prominent in the work, represented in part by the number of canticas and their lengths. Additionally, the verse scheme used, terza rima, is hendecasyllabic (lines of eleven syllables), with the lines composing tercets according to the rhyme scheme aba, bcb, cdc, ded, ....

Written in the first person, the poem tells of Dante's journey through the three realms of the dead, lasting from the night before Good Friday to the Wednesday after Easter in the spring of 1300. The Roman poet Virgil guides him through Hell and Purgatory; Beatrice, Dante's ideal woman, guides him through Heaven. Beatrice was a Florentine woman whom he had met in childhood and admired from afar in the mode of the then-fashionable courtly lovetradition, which is highlighted in Dante's earlier work La Vita Nuova.[citation needed]

The structure of the three realms follows a common numerical pattern of 9 plus 1, for a total of 10: 9 circles of the Inferno, followed by Lucifer contained at its bottom; 9 rings of Mount Purgatory, followed by the Garden of Edencrowning its summit; and the 9 celestial bodies of Paradiso, followed by the Empyrean containing the very essence of God. Within each group of 9, 7 elements correspond to a specific moral scheme, subdivided into three subcategories, while 2 others of greater particularity are added to total nine. For example, the seven deadly sins of the Catholic Church that are cleansed in Purgatory are joined by special realms for the Late repentant and theexcommunicated by the church. The core seven sins within Purgatory correspond to a moral scheme of love perverted, subdivided into three groups corresponding to excessive love (Lust, Gluttony, Greed), deficient love (Sloth), and malicious love (Wrath, Envy, Pride).[citation needed]

In central Italy's political struggle between Guelphs and Ghibellines, Dante was part of the Guelphs, who in general favored the Papacy over the Holy Roman Emperor. Florence's Guelphs split into factions around 1300: the White Guelphs and the Black Guelphs. Dante was among the White Guelphs who were exiled in 1302 by the Lord-Mayor Cante de' Gabrielli di Gubbio, after troops under Charles of Valois entered the city, at the request of Pope Boniface VIII, who supported the Black Guelphs. This exile, which lasted the rest of Dante's life, shows its influence in many parts of the Comedy, from prophecies of Dante's exile to Dante's views of politics, to the eternal damnation of some of his opponents.[citation needed]

The last word in each of the three canticas is stelle ("stars").

Inferno[edit]

Main article: Inferno (Dante)

The poem begins on the night before Good Friday in the year 1300, "halfway along our life's path" (Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita). Dante is thirty-five years old, half of the biblical lifespan of 70 (Psalms 89:10, Vulgate), lost in a dark wood (understood as sin),[12][13][14] assailed by beasts (a lion, a leopard, and a she-wolf) he cannot evade, and unable to find the "straight way" (diritta via) – also translatable as "right way" – to salvation (symbolized by the sun behind the mountain). Conscious that he is ruining himself and that he is falling into a "low place" (basso loco) where the sun is silent ('l sol tace), Dante is at last rescued by Virgil, and the two of them begin their journey to the underworld. Each sin's punishment in Inferno is a contrapasso, a symbolic instance of poetic justice; for example, fortune-tellers have to walk with their heads on backwards, unable to see what is ahead, because that was what they had tried to do in life:

Allegorically, the Inferno represents the Christian soul seeing sin for what it really is, and the three beasts represent three types of sin: the self-indulgent, the violent, and the malicious.[16] These three types of sin also provide the three main divisions of Dante's Hell: Upper Hell, outside the city of Dis, for the four sins of indulgence (lust, gluttony,avarice, anger); Circle 7 for the sins of violence; and Circles 8 and 9 for the sins of malice (fraud and treachery). Added to these are two unlike categories that are specifically spiritual: Limbo, in Circle 1, contains the virtuous pagans who were not sinful but were ignorant of Christ, and Circle 6 contains the heretics who contradicted the doctrine and confused the spirit of Christ. The circles number 9, with the addition of Satan completing the structure of 9 + 1 = 10.[17]

Purgatorio[edit]

Main article: Purgatorio

Having survived the depths of Hell, Dante and Virgil ascend out of the undergloom to the Mountain of Purgatory on the far side of the world. The Mountain is on an island, the only land in the Southern Hemisphere, created by the displacement of rock which resulted when Satan's fall created Hell[18] (which Dante portrays as existing underneathJerusalem[19]). The mountain has seven terraces, corresponding to the seven deadly sins or "seven roots of sinfulness."[20] The classification of sin here is more psychological than that of the Inferno, being based on motives, rather than actions. It is also drawn primarily from Christian theology, rather than from classical sources.[21]However, Dante's illustrative examples of sin and virtue draw on classical sources as well as on the Bible and on contemporary events.

Love, a theme throughout the Divine Comedy, is particularly important for the framing of sin on the Mountain of Purgatory. While the love that flows from God is pure, it can become sinful as it flows through humanity. Humans can sin by using love towards improper or malicious ends (Wrath, Envy, Pride), or using it to proper ends but with love that is either not strong enough (Sloth) or love that is too strong (Lust, Gluttony, Greed). Below the seven purges of the soul is the Ante-Purgatory, containing the Excommunicated from the church and the Late repentant who died, often violently, before receiving rites. Thus the total comes to nine, with the addition of the Garden of Eden at the summit, equaling ten.[22]

Allegorically, the Purgatorio represents the Christian life. Christian souls arrive escorted by an angel, singing In exitu Israel de Aegypto. In his Letter to Cangrande, Dante explains that this reference to Israel leaving Egypt refers both to the redemption of Christ and to "the conversion of the soul from the sorrow and misery of sin to the state of grace."[23] Appropriately, therefore, it is Easter Sunday when Dante and Virgil arrive.

The Purgatorio is notable for demonstrating the medieval knowledge of aspherical Earth. During the poem, Dante discusses the different stars visible in the southern hemisphere, the altered position of the sun, and the varioustimezones of the Earth. At this stage it is, Dante says, sunset at Jerusalem, midnight on the River Ganges, and sunrise in Purgatory.

Paradiso[edit]

Main article: Paradiso (Dante)

After an initial ascension, Beatrice guides Dante through the nine celestial spheres of Heaven. These are concentric and spherical, as in Aristotelianand Ptolemaic cosmology. While the structures of the Inferno and Purgatoriowere based on different classifications of sin, the structure of the Paradiso is based on the four cardinal virtues and the three theological virtues.

The first seven spheres of Heaven deal solely with the cardinal virtues ofPrudence, Fortitude, Justice and Temperance. The first three describe a deficiency of one of the cardinal virtues – the Moon, containing the inconstant, whose vows to God waned as the moon and thus lack fortitude; Mercury, containing the ambitious, who were virtuous for glory and thus lacked justice; and Venus, containing the lovers, whose love was directed towards another than God and thus lacked Temperance. The final four incidentally are positive examples of the cardinal virtues, all led on by the Sun, containing the prudent, whose wisdom lighted the way for the other virtues, to which the others are bound (constituting a category on its own). Mars contains the men of fortitude who died in the cause of Christianity; Jupiter contains the kings of Justice; and Saturn contains the temperate, the monks who abided by the contemplative lifestyle. The seven subdivided into three are raised further by two more categories: the eighth sphere of the fixed stars that contain those who achieved the theological virtues of faith, hope and love, and represent the Church Triumphant – the total perfection of humanity, cleansed of all the sins and carrying all the virtues of heaven; and the ninth circle, or Primum Mobile(corresponding to the Geocentricism of Medieval astronomy), which contains the angels, creatures never poisoned by original sin. Topping them all is the Empyrean, which contains the essence of God, completing the 9-fold division to 10.

Dante meets and converses with several great saints of the Church, including Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventure, Saint Peter, and St. John. The Paradiso is consequently more theological in nature than the Inferno and the Purgatorio. However, Dante admits that the vision of heaven he receives is merely the one his human eyes permit him to see, and thus the vision of heaven found in the Cantos is Dante's personal vision.

The Divine Comedy finishes with Dante seeing the Triune God. In a flash of understanding that he cannot express, Dante finally understands the mystery of Christ's divinity and humanity, and his soul becomes aligned with God's love:[24]

Earliest manuscripts[edit]

According to the Italian Dante Society, no original manuscript written by Dante has survived, although there are many manuscript copies from the 14th and 15th centuries – more than 825 are listed on their site.[26]

Earliest printed editions[edit]

The first printed edition was published in Foligno, Italy, by Johann Numeister and Evangelista Angelini da Trevi on11 April 1472.[27] Of the 300 copies printed, fourteen still survive. The original printing press is on display in theOratorio della Nunziatella in Foligno.

| Date | Title | Place | Publisher | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1472 | La commedia | Foligno | Johann Numeister and Evangelista Angelini da Trevi | First printed edition |

| 1477 | La commedia | Venice | Wendelin of Speyer | |

| 1481 | Comento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la Comedia di Dante Alighieri | Florence | Nicolaus Laurentii | With Cristoforo Landino's commentary in Italian |

| 1491 | Comento di Christophoro Landino fiorentino sopra la Comedia di Dante Alighieri | Venice | Pietro di Piasi | First fully illustrated edition |

| 1506 | Commedia di Dante insieme con uno diagolo circa el sito forma et misure dello inferno | Florence | Philippo di Giunta | |

| 1555 | La Divina Comedia di Dante | Venice | Gabriel Giolito | First use of "Divine" in title |

Thematic concerns[edit]

The Divine Comedy can be described simply as an allegory: each canto, and the episodes therein, can contain many alternative meanings. Dante's allegory, however, is more complex, and, in explaining how to read the poem – see the Letter to Cangrande[28] – he outlines other levels of meaning besides the allegory: the historical, the moral, the literal, and the anagogical.

The structure of the poem, likewise, is quite complex, with mathematical and numerological patterns arching throughout the work, particularly threes and nines, which are related to the Trinity. The poem is often lauded for its particularly human qualities: Dante's skillful delineation of the characters he encounters in Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise; his bitter denunciations of Florentine and Italian politics; and his powerful poetic imagination. Dante's use of real characters, according to Dorothy Sayers in her introduction to her translation of the Inferno, allows Dante the freedom of not having to involve the reader in description, and allows him to "[make] room in his poem for the discussion of a great many subjects of the utmost importance, thus widening its range and increasing its variety."[29]

Dante called the poem "Comedy" (the adjective "Divine" was added later in the 16th century) because poems in the ancient world were classified as High ("Tragedy") or Low ("Comedy").[30] Low poems had happy endings and were written in everyday language, whereas High poems treated more serious matters and were written in an elevated style. Dante was one of the first in the Middle Ages to write of a serious subject, the Redemption of humanity, in the low and "vulgar" Italian language and not the Latin one might expect for such a serious topic. Boccaccio's account that an early version of the poem was begun by Dante in Latin is still controversial.[31][32]

Scientific themes[edit]

Although the Divine Comedy is primarily a religious poem, discussing sin, virtue, and theology, Dante also discusses several elements of the science of his day (this mixture of science with poetry has received both praise and blame over the centuries[33]). The Purgatorio repeatedly refers to the implications of a spherical Earth, such as the different stars visible in the southern hemisphere, the altered position of the sun, and the various timezones of the Earth. For example, at sunset in Purgatory it is midnight at the Ebro (a river in Spain), dawn in Jerusalem, and noon on the River Ganges:[34]

- Just as, there where its Maker shed His blood,

- the sun shed its first rays, and Ebro lay

- beneath high Libra, and the ninth hour's rays

- were scorching Ganges' waves; so here, the sun

- stood at the point of day's departure when

- God's angel—happy—showed himself to us.[35]

Dante travels through the centre of the Earth in the Inferno, and comments on the resulting change in the direction of gravity in Canto XXXIV (lines 76–120). A little earlier (XXXIII, 102–105), he queries the existence of wind in the frozen inner circle of hell, since it has no temperature differentials.[36]

Inevitably, given its setting, the Paradiso discusses astronomy extensively, but in the Ptolemaic sense. The Paradiso also discusses the importance of theexperimental method in science, with a detailed example in lines 94–105 of Canto II:

- Yet an experiment, were you to try it,

- could free you from your cavil and the source

- of your arts' course springs from experiment.

- Taking three mirrors, place a pair of them

- at equal distance from you; set the third

- midway between those two, but farther back.

- Then, turning toward them, at your back have placed

- a light that kindles those three mirrors and

- returns to you, reflected by them all.

- Although the image in the farthest glass

- will be of lesser size, there you will see

- that it must match the brightness of the rest.[37]

A briefer example occurs in Canto XV of the Purgatorio (lines 16–21), where Dante points out that both theory and experiment confirm that the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection. Other references to science in the Paradiso include descriptions of clockwork in Canto XXIV (lines 13–18), andThales' theorem about triangles in Canto XIII (lines 101–102).

Galileo Galilei is known to have lectured on the Inferno, and it has been suggested that the poem may have influenced some of Galileo's own ideas regarding mechanics.[38]

Theories of influence from Islamic philosophy[edit]

In 1919, Miguel Asín Palacios, a Spanish scholar and a Catholic priest, published La Escatología musulmana en la Divina Comedia (Islamic Eschatology in the Divine Comedy), an account of parallels between early Islamic philosophy and the Divine Comedy. Palacios argued that Dante derived many features of and episodes about the hereafter from the spiritual writings of Ibn Arabi and from the Isra and Mi'raj or night journey of Muhammad to heaven. The latter is described in the Hadith and the Kitab al Miraj (translated into Latin in 1264 or shortly before[39] as Liber Scalae Machometi, "The Book of Muhammad's Ladder"), and has significant similarities to the Paradiso, such as a sevenfold division of Paradise,[40] although this is not unique to the Kitab al Miraj.

Some "superficial similarities"[41] of the Divine Comedy to the Resalat Al-Ghufran or Epistle of Forgiveness of Al-Ma'arri have also been mentioned in this debate. The Resalat Al-Ghufran describes the journey of the poet in the realms of the afterlife and includes dialogue with people in Heaven and Hell, although, unlike the Kitab al Miraj, there is little description of these locations,[42] and it is unlikely that Dante borrowed from this work.[43][44]

Dante did, however, live in a Europe of substantial literary and philosophical contact with the Muslim world, encouraged by such factors as Averroism("Averrois, che'l gran comento feo" Commedia, Inferno, IV, 144, meaning "Averrois, who wrote the great comment") and the patronage of Alfonso X of Castile. Of the twelve wise men Dante meets in Canto X of the Paradiso, Thomas Aquinas and, even more so, Siger of Brabant were strongly influenced by Arabic commentators on Aristotle.[45] Medieval Christian mysticism also shared the Neoplatonic influence of Sufis such as Ibn Arabi. Philosopher Frederick Copleston argued in 1950 that Dante's respectful treatment of Averroes, Avicenna, and Siger of Brabant indicates his acknowledgement of a "considerable debt" to Islamic philosophy.[45]

Although this philosophical influence is generally acknowledged, many scholars have not been satisfied that Dante was influenced by the Kitab al Miraj. The 20th century Orientalist Francesco Gabrieli expressed skepticism regarding the claimed similarities, and the lack of evidence of a vehicle through which it could have been transmitted to Dante. Even so, while dismissing the probability of some influences posited in Palacios' work,[46] Gabrieli conceded that it was "at least possible, if not probable, that Dante may have known the Liber scalae and have taken from it certain images and concepts of Muslim eschatology". Shortly before her death, the Italian philologist Maria Corti pointed out that, during his stay at the court of Alfonso X, Dante's mentor Brunetto Latini met Bonaventura de Siena, a Tuscan who had translated the Kitab al Miraj from Arabic into Latin. Corti speculates that Brunetto may have provided a copy of that work to Dante.[47] René Guénon, a Sufi convert and scholar of Ibn Arabi, rejected in The Esoterism of Dante the theory of his influence (direct or indirect) on Dante.[48]

Literary influence in the English-speaking world and beyond[edit]

The Divine Comedy was not always as well-regarded as it is today. Although recognized as a masterpiece in the centuries immediately following its publication,[49] the work was largely ignored during the Enlightenment, with some notable exceptions such as Vittorio Alfieri; Antoine de Rivarol, who translated the Inferno into French; andGiambattista Vico, who in the Scienza nuova and in the Giudizio su Dante inaugurated what would later become the romantic reappraisal of Dante, juxtaposing him to Homer.[50] The Comedy was "rediscovered" in the English-speaking world by William Blake – who illustrated several passages of the epic – and the romantic writers of the 19th century. Later authors such as T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Samuel Beckett, C. S. Lewis and James Joyce have drawn on it for inspiration. The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was its first American translator,[51] and modern poets, including Seamus Heaney,[52] Robert Pinsky, John Ciardi, W. S. Merwin, and Stanley Lombardo, have also produced translations of all or parts of the book. In Russia, beyond Pushkin's translation of a few tercets,[53] Osip Mandelstam's late poetry has been said to bear the mark of a "tormented meditation" on the Comedy.[54] In 1934, Mandelstam gave a modern reading of the poem in his labyrinthine "Conversation on Dante".[55] In T. S. Eliot's estimation, "Dante and Shakespeare divide the world between them. There is no third."[56] For Jorge Luis Borgesthe Divine Comedy was "the best book literature has achieved".[57]

English translations[edit]

Main article: English translations of Dante's Divine comedy

New English translations of the Divine Comedy continue to be published regularly. Notable English translations of the complete poem include the following.[58]

| Year | Translator | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1805–1814 | Henry Francis Cary | An older translation, widely available online. |

| 1867 | Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | The first U.S. translation, raising American interest in the poem. It is still widely available, including online. |

| 1891–1892 | Charles Eliot Norton | Translation used by Great Books of the Western World. Available online at Project Gutenberg. |

| 1933–1943 | Laurence Binyon | An English version rendered in terza rima, with some advisory assistance from Ezra Pound |

| 1949–1962 | Dorothy L. Sayers | Translated for Penguin Classics, intended for a wider audience, and completed by Barbara Reynolds. |

| 1954–1970 | John Ciardi | His Inferno was recorded and released by Folkways Records in 1954. |

| 1970–1991 | Charles S. Singleton | Literal prose version with extensive commentary; 6 vols. |

| 1981 | C. H. Sisson | Available in Oxford World's Classics. |

| 1980–1984 | Allen Mandelbaum | Available online. |

| 1967–2002 | Mark Musa | An alternative Penguin Classics version. |

| 2000–2007 | Robert and Jean Hollander | Online as part of the Princeton Dante Project. |

| 2002–2004 | Anthony M. Esolen | Modern Library Classics edition. |

| 2006–2007 | Robin Kirkpatrick | A third Penguin Classics version, replacing Musa's. |

| 2010 | Burton Raffel | A Northwestern World Classics version. |

| 2013 | Clive James | A poetic version in quatrains. |

A number of other translators, such as Robert Pinsky, have translated the Inferno only.

In the arts[edit]

Main article: Dante and his Divine Comedy in popular culture

The Divine Comedy has been a source of inspiration for countless artists for almost seven centuries. There are many references to Dante's work in literature. In music, Franz Liszt was one of many composers to write works based on theDivine Comedy. In sculpture, the work of Auguste Rodin includes themes from Dante, and many visual artists have illustrated Dante's work, as shown by the examples above. There have also been many references to the Divine Comedy incinema and computer games.

Gallery[edit]

| Series of woodcuts illustrating Dante’s Hell by Antonio Manetti (1423–1497): From Dialogo di Antonio Manetti, cittadino fiorentino, circa al sito, forma, et misure dello inferno di Dante Alighieri poeta excellentissimo(Florence: F. Giunta, 1510?) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| La materia della Divina commedia di Dante Alighieri, dichiarata in VI tavole, by Michelangelo Caetani (1804–1882) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

See also[edit]

- Allegory in the Middle Ages

- List of cultural references in Divine Comedy

- Paradise Lost

- Book of Arda Viraf

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ For example, Encyclopedia Americana, 2006, Vol. 30. p. 605: "the greatest single work of Italian literature;" John Julius Norwich, The Italians: History, Art, and the Genius of a People, Abrams, 1983, p. 27: "his tremendous poem, still after six and a half centuries the supreme work of Italian literature, remains – after the legacy of ancient Rome – the grandest single element in the Italian heritage;" and Robert Reinhold Ergang, The Renaissance, Van Nostrand, 1967, p. 103: "Many literary historians regard the Divine Comedy as the greatest work of Italian literature. In world literature it is ranked as an epic poem of the highest order."

- ^ Bloom, Harold (1994). The Western Canon. See also Western canon for other "canons" that include the Divine Comedy.

- ^ See Lepschy, Laura; Lepschy, Giulio (1977). The Italian Language Today.or any other history of Italian language.

- ^ Peter E. Bondanella, The Inferno, Introduction, p. xliii, Barnes & Noble Classics, 2003, ISBN 1-59308-051-4: "the key fiction of the Divine Comedy is that the poem is true."

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on page 19.

- ^ Charles Allen Dinsmore, The Teachings of Dante, Ayer Publishing, 1970, p. 38, ISBN 0-8369-5521-8.

- ^ The Fordham Monthly Fordham University, Vol. XL, Dec. 1921, p. 76

- ^ Ronnie H. Terpening, Lodovico Dolce, Renaissance Man of Letters(Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 1997), p. 166.

- ^ Dante The Inferno A Verse Translation by Professor Robert and Jean Hollander page 43

- ^ Epist. XIII 43 to 48

- ^ Wilkins E.H The Prologue to the Divine Comedy Annual Report of the Dante Society, pp. 1-7.

- ^ "Inferno, la Divina Commedia annotata e commentata da Tommaso Di Salvo, Zanichelli, Bologna, 1985". Abebooks.it. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ Lectura Dantis, Società dantesca italiana

- ^ Online sources include [1], [2], [3] [4], [5], [6], and [7]Archived November 11, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Inferno, Canto XX, lines 13–15 and 38–39, Mandelbaum translation.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory, notes on page 75.

- ^ Carlyle-Okey-Wicksteed, Divine Comedy, "Notes to Dante's Inferno"

- ^ Inferno, Canto 34, lines 121–126.

- ^ Richard Lansing and Teodolinda Barolini, The Dante Encyclopedia, p. 475, Garland Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0-8153-1659-3.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory, Introduction, pp. 65–67 (Penguin, 1955).

- ^ Robin Kirkpatrick, Purgatorio, Introduction, p. xiv (Penguin, 2007).

- ^ Carlyle-Oakey-Wickstead, Divine Comedy, "Notes on Dante's Purgatory.

- ^ "The Letter to Can Grande," in Literary Criticism of Dante Alighieri, translated and edited by Robert S. Haller (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1973), 99

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Paradise, notes on Canto XXXIII.

- ^ Paradiso, Canto XXXIII, lines 142–145, C. H. Sisson translation.

- ^ "Elenco Codici". Danteonline.it. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ^ Christopher Kleinhenz, Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1, Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0-415-93930-5, p. 360.

- ^ "Epistle to Can Grande". faculty.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, Introduction, p. 16 (Penguin, 1955).

- ^ "Ancient History Encyclopedia".

- ^ Boccaccio also quotes the initial triplet:"Ultima regna canam fluvido contermina mundo, / spiritibus quae lata patent, quae premia solvunt /pro meritis cuicumque suis". For translation and more, see Guyda Armstrong,Review of Giovanni Boccaccio. Life of Dante. J. G. Nichols, trans. London: