باشقیرها (به سیریلیک: Башҡорттар) مردمانی از اقوام ترک ساکن آسیای میانه هستند. جمعیت آنان حدود ۱٬۸۰۰٬۰۰۰ نفر برآورد میشود که بیشتر در جمهوری باشقیرستان، روسیه زندگی میکنند.[۱۱] جمعیت باشقیرهای ساکن تاتارستان نیز قابل توجه است.مناطق اصلی زندگی باشقیرها در روسیه به غیر از تاتارستانو باشقیرستان ، شامل استان چیلیابینسک، استان ارنبورگ، سرزمین پرم، استان سامارا میباشد. همچنین باشقیرها بجز روسیه در کشورهایی مانند اوکراین، قزاقستان و تا حدودی ازبکستان هم ساکنند.

زبان باشقیرها، باشقیری نام دارد. این زبان از خانواده زبانهای آلتایی، شاخه زبانهای قبچاق بوده و بسیار نزدیک به زبان تاتار است. اکثر باشقیرها روسی را نیز میدانند. دین باشقیرها نیز عمدتاً اسلام است.

محتویات [نهفتن]

۱ریشه شناسی نام

۲ریشه نژادی باشقیرها

۳تاریخ

۴فرهنگ

۵منابع

۶پیوند به بیرون

ریشه شناسی نام[ویرایش]

در مورد ریشه نام باشقیرها گمانه زنی های متفاوتی وجود دارد. که تا کنون هیچکدام از آنها بصورت رسمی پذیرفته نشده است. در زبان باشقیری نام این قوم باشقورت است.

آر.جی کوزیف نژادشناس مشهور بر این باور است که این نام از ترکیب (باش) بمعنی سر و (قورد) به معنی ایل ساخته شده است.

بر اساس ریشه شناسی های مربوط به قرن هجدهم نام باشقورت را بمعنی رهبر گرگان با گرگ رهبر دانستهاند.

دیگر مردم شناس روس بنام آلکتروف در دهه های پایانی سده نوزدهم پیشنهاد داد که نام این ایل به معنی ملت متفاوت یا ویژه بوده است.

ترک شناس مشهور دیگر بنام باسکاکوف مطرح نمود که باش در اصل (bẚdz) بوده و معنی برادر زن یا باجناق می داده و (gur) نیز به نام اوگریا یا مردمان فینواوگری اشاره دارد.

داگلاس مورتون دانلپ اعتقاد دارد که نام های بلغار و باشقیر همریشه هستند و معنی باشقیر را از بش قوریا بش گور یعنی پنج طایفه اوگریایی می داند.

ریشه نژادی باشقیرها[ویرایش]

شناخت اصالت و ریشه و تبار باشقیرها تا حد زیادی پیچیده است. منطقه اصلی زندگی باشقیرها جنوب شرقی اورال و استپ های مجاور بوده که از دیرباز به مردمانی با تبارهای گوناگون و ریشه های نژادی فرهنگی متفاوت تعلق داشته است. در زمینه ریشه نژادی باشقیرها بصورت کلی سه نطریه اصلی و برجسته وجود دارد.

نظریه ریشه ترکی.[۱۲][۱۳][۱۴][۱۵]

نظریه ریشه فینو اوگریایی.[۱۶][۱۷][۱۵]

نظریه ریشه و تبار ایرانی.[۱۸][۱۵][۱۹][۲۰]

تاریخ[ویرایش]

سواره باشقیر در سال ۱۸۴۵ میلادی

قدیمی ترین اطلاعاتی که درباره باشقیرها در تاریخ ثبت شده است به نویسندگان مسلمانی نظیر سلام ترجمان، ابن فضلان وابوزید بلخی در سده های نهم و دهم میلادی باز می گردد. این منابع باشقیرها را به دو دسته مجزا در استپ های اورال و حاشیه رود دانوب در جوار ممالک بیزانس بخش بندی کردهاند. ابن رسته گزارش می دهد باشقیرها ضمن فتح کوههای اورال حوالی رود ولگا را هم در دست خویش داشتهاند. در سده دوازدهم میلادی نخستین گزارش اروپایی ها درباره باشقیرها ثبت شده است که دو سیاح اروپایی ضمن توصیف زندگی باشقیرها نامشان را باستارچی(bastarci) عنوان کرده و بر این عقیده بودهاند که زبان این مردم همان زبان مجارها می باشد. از سده دهم تا چهاردهماسلام میان جوامع باشقیر نفوذ پیدا کرد و دین تمامی این مردم را شامل شد. باشقیرها در سده سیزدهم میلادی تحت سیطرهچنگیزخان مغول در آمدند . پس از پایان استیلای مغول در سده پانزدهم باشقیرها به سه دسته تحت تسلط نوقای، قازان و خانات سیبری از هم جدا شدند. باشقیرها که دوباره سرزمین های بسیاری را -اگرچه بصورت مجزا از یکدیگر- تحت انقیاد خود در آورده بودند به روسیه تزاری پیوستند. در سده های هفدهم و هجدهم شورش های گستردهای از سوی باشقیرها در برابر ارتش روسیه رخ داد که به یک جنگ داخلی تمام عیار تبدیل شد. یکی از رهبران اصلی این شورش ها سعید صدیر نام داشت. این رهبر شورشی کارش در دهه پایانی قرن هفدهم به پایان رسید اما در سال ۱۷۰۵ میلادی بار دیگر یک شورش دیگر در باشقیرستان آغاز شد. سرکوب این شورش برای روسیه دوام چندانی نیاورد و در نهایت در سال ۱۷۳۵ رسماً بین قوای روسیه تزاری و متحدان باشقیر جنگ بوقوع پیوست. این نبرد پس از شش سال بسود روسیه تحت رهبری پتر کبیر به پایان رسید. علت آغاز این نبرد برنامه دولتی روسیه برای تبعید باشقیرها به ایران و یاهندوستان بود. این برنامه به فرماندهی کیریلوف نامی آغاز شد در آغاز صدها روستا در آتش سوختند و هزاران نفر از باشقیرها بدست قوای روسیه تزاری قتلعام شدند. اقدام غافلگیرانه ای که باشقیرها برای مقابله با روس ها بکار بستند موفق واقع نشد و شمار بیشتری از اهالی باشقیر به تبع آن کشته شدند. با این وجود گاهی نیز پیروزی و توفیق از آن باشقیر ها بود و پس از شش سال با اعلام آتش بس در پی مرگ کیریلوف غائله خاتمه یافت و باشقیرها در همان حوال باقیماندند. پس از انقلاب بلشویکی روسیهباشقیرستان در ۱۹۱۹ به عنوان بخشی خودمختار به اتحاد جماهیر شوروی پیوست و هم اکنون نیز دارای یک دولت خودمختار در خاک روسیه بنام باشقیرستان است.

فرهنگ[ویرایش]

ابن فضلان در گزارشی که از باشقیرها در سده دهم ارائه می دهد آن ها را غیر مسلمان توصیف می کند. وی ضمن ارائه اطلاعاتی درباره سنت ها و آیین های مردم باشقیر، دین آن ها را شاخه ای از تنگریسم بیان می کند. باشقیرها امروزه بیشتر مسلمان هستند و روند اسلام آوردن باشقیرها همراه با سایر ایلات و قبایل ترک آسیای مرکزی در حدود سده دهم میلادی آغاز شد. باشقیر ها حنفی مذهب هستند. زبان مردم باشقیر باشقیری نام دارد که در دسته زبانهای قبچاقی قرار میگیرد. بیشتر مردم باشقیر زبان روسی می دانند و برخی این زبان را به مثابه زبان نخست خود بکار می برند.

با وجود زندگی در کشور روسیه برخی از مردم باشقیر همچنان دور از جوامع شهری بسر برده و به زندگی بدوی در استپ ها روزگار میگذرانند. این مردم هنوز برخی حماسه ها و اساطیر کهن خودشان مانند اورال باتیر و آقبوزات را زنده نگهداشته اند. این روایات کهن به رویدادهای نبردهای قهرمانانه پهلوانان باشقیر با نیروهای شیطانی میپردازد.

منابع[ویرایش]

مشارکتکنندگان ویکیپدیا، «Bashkirs»، ویکیپدیای انگلیسی، دانشنامهٔ آزاد (بازیابی در ۲۲ ژوئن ۲۰۱۵).

پرش به بالا↑ Lewis, M. Paul (ed.) (2009). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition.". Dallas, Tex.: SIL International.

پرش به بالا↑ [۱] (2002 census) (روسی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۲] (2009 census) (روسی)

↑ پرش به بالا به:۴٫۰ ۴٫۱ [۳] (2001 census)

پرش به بالا↑ [۴] (2000 census) (روسی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۵] (2009 census) (روسی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۶] (2000 census) (روسی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۷] (2009 census) (روسی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۸] (2011 census) (لتونی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۹] (2000 census)

پرش به بالا↑ سرشماری سال ۲۰۰۲ روسیه

پرش به بالا↑ Р. Г. Кузеев. Происхождение башкирского народа. М, Наука, ۱۹۷۴

پرش به بالا↑ Янғужин Р. З. Башҡорт ҡәбиләләре тарихынан (Из истории башкирских племён). Өфө: «Китап», ۱۹۹۵

پرش به بالا↑ Кузеев Р. Г. Народы Поволжья и Приуралья. М. Наука, ۱۹۸۵

↑ پرش به بالا به:۱۵٫۰ ۱۵٫۱ ۱۵٫۲ Р. М. Юсупов. Краниология башкир. Л., Наука, 1989; Юсупов Р.М. Некоторые проблемы палеоантропологии Южного Урала и этнической истории башкир//XIII Уральское археологическое совещание. Тезисы докладов, часть II, Башkортостан, Уфа, ВЭГУ, 23-25.04.1996, С. 120-123.

پرش به بالا↑ Decsy Gy. Einfuhrung in die finnisch-ugrische Sprachwissenschalft. Wiesbaden, 1965, 149—150.

پرش به بالا↑ М. И. Артамонов. История хазар. М.-Л., ۱۹۶۲, С.۳۳۸.

پرش به بالا↑ Мажитов Н.А., Султанова А.Н. История Башкортостана. Уфа, Китап, 2010, С.108 (Смирнов К.Ф. о дахо-массагетских корнях башкир).

پرش به بالا↑ Зинуров Р.Н. Башкирские восстания и индейские войны - феномен в мировой истории. Уфа, Гилем, 2001, С.11 (прабашкиры - потомки отделившихся скифов).

پرش به بالا↑ Галлямов С. А. Башкорды от Гильгамеша до Заратустры. Уфа, РИО РУНМЦ Госкомнауки РБ, 1999 (О башкордах из родов Тангаур и Гайна).

پیوند به بیرون[ویرایش]

در ویکیانبار پروندههایی دربارهٔباشقیر موجود است.

در ویکیانبار پروندههایی دربارهٔباشقیر موجود است.

وبگاه رسمی جمهوری باشقیرستان

خبرگزاری جمهوری باشقیرستان

تاریخ، فرهنگ و زبان باشقیرها

[نمایش]

ن

ب

و

اقوام ترکتبار

[نمایش]

ن

ب

و

اسلام در اروپا

ردهها:

"Related ethnic groups" needing confirmation

باشقیر

اقوام در ازبکستان

اقوام ترکتبار

اقوام در روسیه

باشقیرستان

جوامع مسلمان

جوامع مسلمان روسیه

اقوام آسیا

////////////////////

The Bashkirs (Bashkir: Башҡорттар başqorttar; Russian: Башкиры) are a Turkic people indigenous toBashkortostan, extending on both sides of the Ural Mountains, on the place where Eastern Europe meetsNorth Asia. Groups of Bashkirs also live in the Republic of Tatarstan, Perm Krai, Chelyabinsk, Orenburg,Tyumen, Sverdlovsk, Kurgan, Samara and Saratov Oblasts of Russia, as well as in Kazakhstan, Ukraine,Uzbekistan and other countries.

Most Bashkirs speak the Bashkir language, which belongs to the Kypchak branch of the Turkic languages and share cultural affinities with the broader Turkic peoples. In religion the Bashkirs are mainly Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi madhhab.

Contents [show]

Ethnonym[edit]

There are several theories regarding the etymology of the endonym Bashqort.

Ethnologist R. G. Kuzeev defines the ethnonym as emanating from "bash" — "main, head" and "qort" — " clan, tribe".

According to the theory of 18th-century ethnographers V. N. Tatishchev, P. I. Richkov, and Johann Gottlieb Georgi, the word "Bashqort" means "wolf-leader of the pack" (bash — "main",qort — "wolf").

In 1847, the historian V. S. Yumatov suggested the meaning as "beekeeper, beemaster".

Russian historian and ethnologist A. E. Alektorov in 1885 suggested that "Bashqort" means "distinct nation".

The Turkologist N. A. Baskakov believed that the word "Bashqort" consists of two parts: "badz(a)" – brother-in-law" and "(o)gur" and means "Ugrics' brother-in-law".

The historian and archaeologist Mikhail Artamonov has identified the Scythian tribe Bušxk' (or Bwsxk) with the ethnonym of modern Bashkirs. HistorianR.H. Hewsen, however, rejects Artamanov's identification and instead identifies the Scythian Bušxk with the Volga Bulgars who were the eastern neighbors of the Bashkirs at that time.[7]

Ethnologist N. V. Bikbulatov's theory states that the term originates from the name of legendary Khazar warlord Bashgird, who was dwelling with two thousand of his warriors in the area of the Jayıq river.

According to Douglas Morton Dunlop: the word "Bashqort" comes from beshgur (or bashgur) which means "five tribes" and, since -sh- in the modern Bashkir language parallels -l- in Bulgar, the names Bashgur and Bulgar are equivalent.

Historian and linguist András Róna-Tas believes the ethonym "Bashkir" is a Bulgar Turkic reflex of the Hungarian self-denomination "Magyar" (Old Hungarian: "Majer").

Recent ethnographic research has supported a link to the Bashkardi people of Hormozgan province, Iran.

History[edit]

Map of Europe, 600 AD

Mausoleum of Huseynbek, first Islamic religious leader of Historical Bashkortostan. 14th-century building

Middle Ages[edit]

Early records on the Bashkirs are found in medieval works by Sallam Tardzheman (9th century) and Ibn-Fadlan(10th century). Al-Balkhi (10th century) described Bashkirs as a people divided into two groups, one inhabiting the Southern Urals, the second group living on the Danube plain near the boundaries of Byzantium——therefore – given the geography and date – referring to either Danube Bulgars or Magyars. Ibn Rustah, a contemporary of Al Balkhi, observed that Bashkirs were an independent people occupying territories on both sides of the Ural mountain ridge between Volga, Kama, and Tobol Rivers and upstream of the Yaik river.

Achmed ibn-Fadlan visited Volga Bulgaria as a staff member in the embassy of the Caliph of Baghdad in 922. He described them as a belligerent Turk nation. Ibn-Fadlan described the Bashkirs as nature worshipers, identifying their deities as various forces of nature, birds and animals. He also described the religion of acculturated Bashkirs as a variant of Tengrism, including 12 'gods' and naming Tengri – lord of the endless blue sky.

The first European sources to mention the Bashkirs are the works of Joannes de Plano Carpini and William of Rubruquis in the mid-13th century. These travelers, encountering Bashkir tribes in the upper parts of the Ural River, called them Pascatir or Bastarci, and asserted that they spoke the same language as the Hungarians.

During the 10th century, Islam spread among the Bashkirs. By the 14th century, Islam had become the dominant religious force in Bashkir society.

By 1236, Bashkortostan was incorporated into the empire of Genghis Khan.

During the 13th and 14th centuries, all of Bashkortostan was part of the Golden Horde. The brother of Batu-Khan, Sheibani, received the Bashkir lands to the east of the Ural Mountains – at that time inhabited by the ancestors of contemporary Kurgan Bashkirs.[citation needed]

During the period of Mongolian-Tatar dominion, some of the Bashkirs became subjects of the Kipchaks.[citation needed] Under the Golden Horde, they were subjected to different elements of the Mongols.[citation needed] After the breakup of the Mongol Empire, the Bashkirs were split between the Kazan Khanate, the Nogay Horde, and Siberian Khanate.[citation needed]

Early modern period[edit]

Bashkir women dressed in dulbega breast cover and kashmau headdress. 1770–1771.

In the late 16th and early 19th centuries Bashkirs occupied the territory from the left bank of the Volga on the south-west to the riverheads of Tobol in the east, from the river Sylva in the north, to the middle stream of the Yaik in the south, in the Middle and Southern Urals, in Cis-Urals, including Volga territory and Trans-Urals.

In the middle of the 16th century, Bashkirs joined the Russian state. Previously they formed parts of the Nogai,Kazan, Sibir, and partly, Astrakhan khanates. Charters of Ivan the Terrible to Bashkir tribes became the basis of their contractual relationship with the tsar’s government. Primary documents pertaining to the Bashkirs during this period have been lost, some are mentioned in the (shezhere) family trees of the Bashkir.

The Bashkirs rebelled in 1662–64 and 1675–83 and 1705–11. In 1676, the Bashkirs rebelled under a leader named Seyid Sadir or 'Seit Sadurov', and the Russian army had great difficulties in ending the rebellion. The Bashkirs rose again in 1707, under Aldar and Kûsyom, on account of ill-treatment by the Russian officials.

1735 Bashkir War[edit]

The main settlement area of the Bashkirs in the late 18th century extends over the Kama, Volga, Samara and Tobol Rivers

Bashkir officers, 1838–1845

The third insurrection occurred in 1735, at the time of the foundation of Orenburg, and it lasted for six years. From at least the time of Peter the Great there had been talk of pushing southeast toward Persia and India. Ivan Kirillov drew up a plan to build a fort to be called Orenburg at Orsk at the confluence of the Or River and the Ural Riversoutheast of the Urals where the Bashkir, Kalmyk and Kazakh lands join. Work was started at Orsk in 1735, but by 1743 'Orenburg' was moved about 250 km west to its present location. The next planned step was to build a fort on the Aral Sea. This would involve crossing the Bashkir country and then the lands of the Kazakh Lesser Horde, some of whom had recently offered a nominal submission.

Kirillov's plan was approved on May 1, 1734 and he was placed in command. He was warned that this would provoke a Bashkir rebellion, but the warnings were ignored. He left Ufa with 2,500 men in 1735 and fighting started on the first of July. The war consisted of many small raids and complex troop movements, so it cannot be easily summarized. For example: In the spring of 1736 Kirillov burned 200 villages, killed 700 in battle and executed 158. An expedition of 773 men left Orenburg in November and lost 500 from cold and hunger. During, at Seiantusa the Bashkir planned to massacre sleeping Russian. The ambush failed. One thousand villagers, including women and children, were put to the sword and another 500 driven into a storehouse and burned to death. Raiding parties then went out and burned about 50 villages and killed another 2,000. Eight thousand Bashkirs attacked a Russian camp and killed 158, losing 40 killed and three prisoners who were promptly hanged. Rebellious Bashkirs raided loyal Bashkirs. Leaders who submitted were sometimes fined one horse per household and sometimes hanged.

Bashkirs fought on both sides (40% of 'Russian' troops in 1740). Numerous leaders rose and fell. The oddest was Karasakal or Blackbeard who pretended to have 82,000 men on the Aral Sea and had his followers proclaim him 'Khan of Bashkiria'. His nose had been partly cut off and he had only one ear. Such mutilations are standard Imperial punishments. The Kazakhs of the Little Horde intervened on the Russian side, then switched to the Bashkirs and then withdrew. Kirillov died of disease during the war and there were several changes of commander. All this was at the time of Empress Anna of Russia and the Russo-Turkish War (1735–1739).

Although the history of the 1735 Bashkir War cannot be easily summarized, its results can be.

The Russian Imperial goal of expansion into Central Asia was delayed to deal with the Bashkir problem.

Bashkiria was pacified in 1735–1740.

Orenburg was established.

The southern side of Bashkiria was fenced off by the Orenburg Line of forts. It ran from Samara on the Volga east up the Samara River to its headwaters, crossed to the middle Ural River and followed it east and then north on the east side of the Urals and went east down the Uy River to Ust-Uisk on the Tobol River where it connected to the ill-defined 'Siberian Line' along the forest-steppe boundary.

In 1740 a report was made of Bashkir losses which gave: Killed: 16,893, Sent to Baltic regiments and fleet: 3,236, Women and children distributed (presumably as serfs): 8,382, Grand Total: 28,511. Fines: Horses: 12,283, Cattle and Sheep: 6,076, Money: 9,828 rubles. Villages destroyed: 696. As this was compiled from army reports it excludes losses from irregular raiding, hunger, disease and cold. All this was from an estimated Bashkir population of 100,000.

Later, in 1774, the Bashkirs, under the leadership of Salavat Yulayev, supported Pugachev's Rebellion. In 1786, the Bashkirs achieved tax-free status; and in 1798 Russia formed an irregular Bashkir army from among them. Residual land ownership disputes continued.

The Bashkirs lived between the Kama, Volga, Samara and Tobol Rivers. The Samara River extends from the hairpin curve of the Volga east to the base of the Urals. The Tobol is east of the Upper Ural River. Orsk is where the Ural turns westward. The Belaya River with the town of Ufa cuts through the center.

Demographics[edit]

The area settled by the Bashkirs in the Volga-Urals region according to the national census of 2010.

Further information: Bashkir language and Bashkortostan

The ethnic Bashkir population is estimated at roughly 2 million people (2009 SIL Ethnologue), of which about 1.4 million speak the Bashkir language, a Turkic language of the Kypchak group. The Russian census of 2002 recorded 1.38 million Bashkir speakers in the Russian Federation. Most Bashkirs are bilingual in Bashkir and Russian.

The 2010 Russian census recorded 1,172,287 ethnic Bashkirs in Bashkortostan (29.5% of total population).

About 50% of Bashkirs are Muslim, 25% are unaffiliated, 11% are atheist, and 2% are pagan. There are also about less than 1% Protestant and Catholic Bashkirs.[8][9]

Culture[edit]

The Bashkirs traditionally practiced agriculture, cattle-rearing and bee-keeping. The half-nomadic Bashkirs wandered either the mountains or the steppes, herding cattle.

Bashkir national dishes include a kind of gruel called öyrä and a cheese named qorot. Wild-hive beekeeping can be named as a separate component of the most ancient culture which is practiced in the same Burzyansky District near to the Shulgan-Tash cave.

«Ural-batyr» and «Akbuzat» are Bashkir national epics. Their plot concerns struggle of heroes against demonic forces. The peculiarity of them is that events and ceremonies described there can be addressed to a specific geographical and historical object –the Shulgan-Tash cave and its vicinities.

Religion[edit]

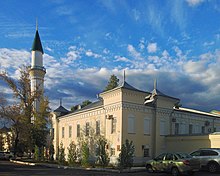

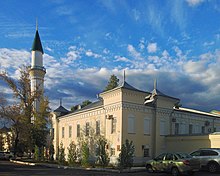

Caravanserai mosque in Orenburg, cultural monument of the Bashkir people, 1837—1844

In the pre-Islamic period the Bashkirs were followers of Tengrianism.[10][11]

Bashkirs began to convert to Islam from in the 9th century.[12] Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan in 921 met some of the Bashkirs, who were Muslims.[13] The final assertion of Islam among the Bashkirs occurred in the 1320s and 1330s (Golden Horde times). On the territory of Bashkortostan preserved the burial place of the first Imam of Historical Bashkortostan — The mausoleum of Hussein-Bek (ru), 14th-century building. In 1788 Catherine the Greatestablished the "Orenburg Mohammedan Spiritual Assembly (ru)" in Ufa, which was the first Muslim administrative center in Russia.

In yearly 1990s began the religious revival among the Bashkirs.[14] According to Talgat Tadzhuddin there are more than 1,000 mosques in Bashkortostan in 2010.[15]

The Bashkirs are predominantly Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi madhhab.[5]

Genetics[edit]

Regarding Y-DNA haplogroups, genetic studies have revealed that most Bashkir males belong to haplogroup R1b (R-M269 and R-M73) which is, on average, found at the frequency of 47,6 %. Following are the haplogroup R1a at the average frequency of 26.5%, and haplogroup N1c at 17%. In lower frequencies were also found haplogroups J2, C, O, E1b, G2a, L, N1b, I, T.[16]

Most mtDNA haplogroups found in Bashkirs (65%) consist of the haplogroups G, D, С, Z and F; which are lineages characteristic of East Eurasian populations. On the other hand, mtDNA haplogroups characteristic of European and Middle Eastern populations were also found in significant amounts (35%).[17][18]

Theories of origin[edit]

The Bashkirs, photo by Mikhail Bukar, 1872.

Because genetic studies have revealed that a majority of Bashkir males belong to Y-DNA Haplogroup R1b, which is otherwise concentrated in Western Europe, this has lent support to theories such as:

the "Kurgan hypothesis", i.e. that the original homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans lay immediately west of theUral Mountains, in or near present-day Bashkortostan,[19] and;

Notable Bashkirs[edit]

Alsou, singer (Bashkir father)

Lyasan Utiasheva, gymnast and TV personality (Bashkir mother)

Ildar Abdrazakov, opera singer

Murtaza Rakhimov, first president of Bashkortostan

Rustem Khamitov, president of Bashkortostan

Zeki Velidi Togan, historian, Turkologist, and leader of the Bashkir revolutionary and liberation movement

Salawat Yulayev, Bashkir national hero

Irek Zaripov, biathlete and cross-country skier

Tagir Kusimov, was a Soviet military leader.

Zaynulla Rasulev, was a Bashkir religious leader in the 19th and early 20th centuries

Kadir Timergazin, was also a Soviet petroleum geologist, the first doctor and professor of geological-mineralogical sciences from the Bashkirs, an honored scientist of the RSFSR.

Mustai Karim, was a Bashkir Soviet poet, writer and playwright. He was named People's poet of the Bashkir Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (1963), Hero of Socialist Labour (1979), and winner of the Lenin Prize (1984) and the State Prize of the USSR (1972).

Shaikhzada Babich, was a Bashkir poet, writer and playwright. Member of the Bashkir national liberation movement, one of the members of the Bashkir government (1917–1919).

Kharrasov Mukhamet – was a rector of the Bashkir State University (2000–2010), Ph.D in physics, Honorary worker of Higher professional Education of Russia (2002).

Yaroslava Shvedova - Kazakhstani tennis player (Bashkir mother)

References[edit]

Jump up^ Lewis, M. Paul (ed.) (2009). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition.". Dallas, Tex.: SIL International.

Jump up^ "ВПН-2010". Perepis-2010.ru. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

Jump up^ [1] Archived September 14, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

Jump up^ "8. НАСЕЛЕНИЕ НАИБОЛЕЕ МНОГОЧИСЛЕННЫХ" (PDF). Gks.ru. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

^ Jump up to:a b "Bashkortostan and Bashkirs", Encyclopedia.com

Jump up^ "Bashkirs", Great Russian Encyclopedia

Jump up^ Peter B. Golden, Haggai Ben-Shammai & András Róna-Tas, The World of the Khazars: New Perspectives, Leiden/Boston, Brill, 2007, pp. 422-423.

Jump up^ "Главная страница проекта "Арена" : Некоммерческая Исследовательская Служба "Среда"". Sreda.org. Retrieved 16 March2015.

Jump up^ "Numerical analysis" (JPG). Sreda.org. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

Jump up^ Shireen Hunter, Jeffrey L. Thomas, Alexander Melikishvili, "Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security", M.E. Sharpe Inc.

Jump up^ К вопросу о тенгрианстве башкир // Compatriot, Popular Science Magazine (Russian)

Jump up^ Shirin Akiner, "Islamic Peoples Of The Soviet Un", Second edition, 1986

Jump up^ Allen J. Frank, "Islamic Historiography and "Bulghar" Identity Among the Tatars and Bashkirs", Brill, 1998

Jump up^ Jeffrey E. Cole, "Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia", Greenwood publishing group

Jump up^ Интерфакс. Говорить о притеснении ислама в России кощунственно, считает Талгат Таджуддин // Interfax, 17.12.2010

Jump up^ Лобов А. С. Структура генофонда субпопуляций башкир. Диссертация кандидата биологических наук. — Уфа, 2009.- 131 с.

Jump up^ С. А. Лимборская, Э. К. Хуснутдинова, Е. В. Балановская. Этногеномика и геногеография народов Восточной Европы. Институт молекулярной генетики РАН. Уфимский научный центр. Медико-генетический научный центр РАМН. М. Наука. 2002. С.179-180

Jump up^ Антропология башкир/Бермишева М. А., Иванов В. А., Киньябаева Г. А. и др. СПб., Алетейя, 2011, 496 с., С.339.

Jump up^ See, for example: Will Chang, Chundra Cathcart, David Hall, & Andrew Garrett, 'Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis supports the Indo-European steppe hypothesis', Language, vol. 91, no. 1 (March) 2015, p. 196.

Sources[edit]

Frhn, "De Baskiris", in Mrn. de l'Acad. de St-Pitersbourg, 1822.

J. P. Carpini, "Liber Tartarorum", edited under the title "Relations des Mongols ou Tartares", by d'Avezac (Paris, 1838).

Semenoff, "Geographical-statistic Dictionary of Russian Empire", 1863.

Florinsky, in "Vestnik Evropy" magazine, 1874.

Katarinskij, "Dictionnaire Bashkir-Russe", 1900.

Gulielmus de Rubruquis, "The Journey of William of Rubruck to the Eastern Parts of the World", translated by V.W. Rockhill (London, 1900).

William of Rubruck's "Account of the Mongols", 1900.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bashkirs". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bashkirs". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Alton S. Donnelly, "The Russian Conquest of Bashkiria 1552–1740": Yale Univ. Press, 1968.

Summerfield, Stephen Cossack Hurrah: Russian Irregular Cavalry Organisation and Uniforms during the Napoleonic Wars, Partizan Press, 2005 ISBN 1-85818-513-0

External links[edit]

زبان باشقیرها، باشقیری نام دارد. این زبان از خانواده زبانهای آلتایی، شاخه زبانهای قبچاق بوده و بسیار نزدیک به زبان تاتار است. اکثر باشقیرها روسی را نیز میدانند. دین باشقیرها نیز عمدتاً اسلام است.

محتویات [نهفتن]

۱ریشه شناسی نام

۲ریشه نژادی باشقیرها

۳تاریخ

۴فرهنگ

۵منابع

۶پیوند به بیرون

ریشه شناسی نام[ویرایش]

در مورد ریشه نام باشقیرها گمانه زنی های متفاوتی وجود دارد. که تا کنون هیچکدام از آنها بصورت رسمی پذیرفته نشده است. در زبان باشقیری نام این قوم باشقورت است.

آر.جی کوزیف نژادشناس مشهور بر این باور است که این نام از ترکیب (باش) بمعنی سر و (قورد) به معنی ایل ساخته شده است.

بر اساس ریشه شناسی های مربوط به قرن هجدهم نام باشقورت را بمعنی رهبر گرگان با گرگ رهبر دانستهاند.

دیگر مردم شناس روس بنام آلکتروف در دهه های پایانی سده نوزدهم پیشنهاد داد که نام این ایل به معنی ملت متفاوت یا ویژه بوده است.

ترک شناس مشهور دیگر بنام باسکاکوف مطرح نمود که باش در اصل (bẚdz) بوده و معنی برادر زن یا باجناق می داده و (gur) نیز به نام اوگریا یا مردمان فینواوگری اشاره دارد.

داگلاس مورتون دانلپ اعتقاد دارد که نام های بلغار و باشقیر همریشه هستند و معنی باشقیر را از بش قوریا بش گور یعنی پنج طایفه اوگریایی می داند.

ریشه نژادی باشقیرها[ویرایش]

شناخت اصالت و ریشه و تبار باشقیرها تا حد زیادی پیچیده است. منطقه اصلی زندگی باشقیرها جنوب شرقی اورال و استپ های مجاور بوده که از دیرباز به مردمانی با تبارهای گوناگون و ریشه های نژادی فرهنگی متفاوت تعلق داشته است. در زمینه ریشه نژادی باشقیرها بصورت کلی سه نطریه اصلی و برجسته وجود دارد.

نظریه ریشه ترکی.[۱۲][۱۳][۱۴][۱۵]

نظریه ریشه فینو اوگریایی.[۱۶][۱۷][۱۵]

نظریه ریشه و تبار ایرانی.[۱۸][۱۵][۱۹][۲۰]

تاریخ[ویرایش]

سواره باشقیر در سال ۱۸۴۵ میلادی

قدیمی ترین اطلاعاتی که درباره باشقیرها در تاریخ ثبت شده است به نویسندگان مسلمانی نظیر سلام ترجمان، ابن فضلان وابوزید بلخی در سده های نهم و دهم میلادی باز می گردد. این منابع باشقیرها را به دو دسته مجزا در استپ های اورال و حاشیه رود دانوب در جوار ممالک بیزانس بخش بندی کردهاند. ابن رسته گزارش می دهد باشقیرها ضمن فتح کوههای اورال حوالی رود ولگا را هم در دست خویش داشتهاند. در سده دوازدهم میلادی نخستین گزارش اروپایی ها درباره باشقیرها ثبت شده است که دو سیاح اروپایی ضمن توصیف زندگی باشقیرها نامشان را باستارچی(bastarci) عنوان کرده و بر این عقیده بودهاند که زبان این مردم همان زبان مجارها می باشد. از سده دهم تا چهاردهماسلام میان جوامع باشقیر نفوذ پیدا کرد و دین تمامی این مردم را شامل شد. باشقیرها در سده سیزدهم میلادی تحت سیطرهچنگیزخان مغول در آمدند . پس از پایان استیلای مغول در سده پانزدهم باشقیرها به سه دسته تحت تسلط نوقای، قازان و خانات سیبری از هم جدا شدند. باشقیرها که دوباره سرزمین های بسیاری را -اگرچه بصورت مجزا از یکدیگر- تحت انقیاد خود در آورده بودند به روسیه تزاری پیوستند. در سده های هفدهم و هجدهم شورش های گستردهای از سوی باشقیرها در برابر ارتش روسیه رخ داد که به یک جنگ داخلی تمام عیار تبدیل شد. یکی از رهبران اصلی این شورش ها سعید صدیر نام داشت. این رهبر شورشی کارش در دهه پایانی قرن هفدهم به پایان رسید اما در سال ۱۷۰۵ میلادی بار دیگر یک شورش دیگر در باشقیرستان آغاز شد. سرکوب این شورش برای روسیه دوام چندانی نیاورد و در نهایت در سال ۱۷۳۵ رسماً بین قوای روسیه تزاری و متحدان باشقیر جنگ بوقوع پیوست. این نبرد پس از شش سال بسود روسیه تحت رهبری پتر کبیر به پایان رسید. علت آغاز این نبرد برنامه دولتی روسیه برای تبعید باشقیرها به ایران و یاهندوستان بود. این برنامه به فرماندهی کیریلوف نامی آغاز شد در آغاز صدها روستا در آتش سوختند و هزاران نفر از باشقیرها بدست قوای روسیه تزاری قتلعام شدند. اقدام غافلگیرانه ای که باشقیرها برای مقابله با روس ها بکار بستند موفق واقع نشد و شمار بیشتری از اهالی باشقیر به تبع آن کشته شدند. با این وجود گاهی نیز پیروزی و توفیق از آن باشقیر ها بود و پس از شش سال با اعلام آتش بس در پی مرگ کیریلوف غائله خاتمه یافت و باشقیرها در همان حوال باقیماندند. پس از انقلاب بلشویکی روسیهباشقیرستان در ۱۹۱۹ به عنوان بخشی خودمختار به اتحاد جماهیر شوروی پیوست و هم اکنون نیز دارای یک دولت خودمختار در خاک روسیه بنام باشقیرستان است.

فرهنگ[ویرایش]

ابن فضلان در گزارشی که از باشقیرها در سده دهم ارائه می دهد آن ها را غیر مسلمان توصیف می کند. وی ضمن ارائه اطلاعاتی درباره سنت ها و آیین های مردم باشقیر، دین آن ها را شاخه ای از تنگریسم بیان می کند. باشقیرها امروزه بیشتر مسلمان هستند و روند اسلام آوردن باشقیرها همراه با سایر ایلات و قبایل ترک آسیای مرکزی در حدود سده دهم میلادی آغاز شد. باشقیر ها حنفی مذهب هستند. زبان مردم باشقیر باشقیری نام دارد که در دسته زبانهای قبچاقی قرار میگیرد. بیشتر مردم باشقیر زبان روسی می دانند و برخی این زبان را به مثابه زبان نخست خود بکار می برند.

با وجود زندگی در کشور روسیه برخی از مردم باشقیر همچنان دور از جوامع شهری بسر برده و به زندگی بدوی در استپ ها روزگار میگذرانند. این مردم هنوز برخی حماسه ها و اساطیر کهن خودشان مانند اورال باتیر و آقبوزات را زنده نگهداشته اند. این روایات کهن به رویدادهای نبردهای قهرمانانه پهلوانان باشقیر با نیروهای شیطانی میپردازد.

منابع[ویرایش]

مشارکتکنندگان ویکیپدیا، «Bashkirs»، ویکیپدیای انگلیسی، دانشنامهٔ آزاد (بازیابی در ۲۲ ژوئن ۲۰۱۵).

پرش به بالا↑ Lewis, M. Paul (ed.) (2009). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition.". Dallas, Tex.: SIL International.

پرش به بالا↑ [۱] (2002 census) (روسی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۲] (2009 census) (روسی)

↑ پرش به بالا به:۴٫۰ ۴٫۱ [۳] (2001 census)

پرش به بالا↑ [۴] (2000 census) (روسی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۵] (2009 census) (روسی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۶] (2000 census) (روسی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۷] (2009 census) (روسی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۸] (2011 census) (لتونی)

پرش به بالا↑ [۹] (2000 census)

پرش به بالا↑ سرشماری سال ۲۰۰۲ روسیه

پرش به بالا↑ Р. Г. Кузеев. Происхождение башкирского народа. М, Наука, ۱۹۷۴

پرش به بالا↑ Янғужин Р. З. Башҡорт ҡәбиләләре тарихынан (Из истории башкирских племён). Өфө: «Китап», ۱۹۹۵

پرش به بالا↑ Кузеев Р. Г. Народы Поволжья и Приуралья. М. Наука, ۱۹۸۵

↑ پرش به بالا به:۱۵٫۰ ۱۵٫۱ ۱۵٫۲ Р. М. Юсупов. Краниология башкир. Л., Наука, 1989; Юсупов Р.М. Некоторые проблемы палеоантропологии Южного Урала и этнической истории башкир//XIII Уральское археологическое совещание. Тезисы докладов, часть II, Башkортостан, Уфа, ВЭГУ, 23-25.04.1996, С. 120-123.

پرش به بالا↑ Decsy Gy. Einfuhrung in die finnisch-ugrische Sprachwissenschalft. Wiesbaden, 1965, 149—150.

پرش به بالا↑ М. И. Артамонов. История хазар. М.-Л., ۱۹۶۲, С.۳۳۸.

پرش به بالا↑ Мажитов Н.А., Султанова А.Н. История Башкортостана. Уфа, Китап, 2010, С.108 (Смирнов К.Ф. о дахо-массагетских корнях башкир).

پرش به بالا↑ Зинуров Р.Н. Башкирские восстания и индейские войны - феномен в мировой истории. Уфа, Гилем, 2001, С.11 (прабашкиры - потомки отделившихся скифов).

پرش به بالا↑ Галлямов С. А. Башкорды от Гильгамеша до Заратустры. Уфа, РИО РУНМЦ Госкомнауки РБ, 1999 (О башкордах из родов Тангаур и Гайна).

پیوند به بیرون[ویرایش]

در ویکیانبار پروندههایی دربارهٔباشقیر موجود است.

در ویکیانبار پروندههایی دربارهٔباشقیر موجود است.وبگاه رسمی جمهوری باشقیرستان

خبرگزاری جمهوری باشقیرستان

تاریخ، فرهنگ و زبان باشقیرها

[نمایش]

ن

ب

و

اقوام ترکتبار

[نمایش]

ن

ب

و

اسلام در اروپا

ردهها:

"Related ethnic groups" needing confirmation

باشقیر

اقوام در ازبکستان

اقوام ترکتبار

اقوام در روسیه

باشقیرستان

جوامع مسلمان

جوامع مسلمان روسیه

اقوام آسیا

////////////////////

The Bashkirs (Bashkir: Башҡорттар başqorttar; Russian: Башкиры) are a Turkic people indigenous toBashkortostan, extending on both sides of the Ural Mountains, on the place where Eastern Europe meetsNorth Asia. Groups of Bashkirs also live in the Republic of Tatarstan, Perm Krai, Chelyabinsk, Orenburg,Tyumen, Sverdlovsk, Kurgan, Samara and Saratov Oblasts of Russia, as well as in Kazakhstan, Ukraine,Uzbekistan and other countries.

Most Bashkirs speak the Bashkir language, which belongs to the Kypchak branch of the Turkic languages and share cultural affinities with the broader Turkic peoples. In religion the Bashkirs are mainly Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi madhhab.

Contents [show]

Ethnonym[edit]

There are several theories regarding the etymology of the endonym Bashqort.

Ethnologist R. G. Kuzeev defines the ethnonym as emanating from "bash" — "main, head" and "qort" — " clan, tribe".

According to the theory of 18th-century ethnographers V. N. Tatishchev, P. I. Richkov, and Johann Gottlieb Georgi, the word "Bashqort" means "wolf-leader of the pack" (bash — "main",qort — "wolf").

In 1847, the historian V. S. Yumatov suggested the meaning as "beekeeper, beemaster".

Russian historian and ethnologist A. E. Alektorov in 1885 suggested that "Bashqort" means "distinct nation".

The Turkologist N. A. Baskakov believed that the word "Bashqort" consists of two parts: "badz(a)" – brother-in-law" and "(o)gur" and means "Ugrics' brother-in-law".

The historian and archaeologist Mikhail Artamonov has identified the Scythian tribe Bušxk' (or Bwsxk) with the ethnonym of modern Bashkirs. HistorianR.H. Hewsen, however, rejects Artamanov's identification and instead identifies the Scythian Bušxk with the Volga Bulgars who were the eastern neighbors of the Bashkirs at that time.[7]

Ethnologist N. V. Bikbulatov's theory states that the term originates from the name of legendary Khazar warlord Bashgird, who was dwelling with two thousand of his warriors in the area of the Jayıq river.

According to Douglas Morton Dunlop: the word "Bashqort" comes from beshgur (or bashgur) which means "five tribes" and, since -sh- in the modern Bashkir language parallels -l- in Bulgar, the names Bashgur and Bulgar are equivalent.

Historian and linguist András Róna-Tas believes the ethonym "Bashkir" is a Bulgar Turkic reflex of the Hungarian self-denomination "Magyar" (Old Hungarian: "Majer").

Recent ethnographic research has supported a link to the Bashkardi people of Hormozgan province, Iran.

History[edit]

Map of Europe, 600 AD

Mausoleum of Huseynbek, first Islamic religious leader of Historical Bashkortostan. 14th-century building

Middle Ages[edit]

Early records on the Bashkirs are found in medieval works by Sallam Tardzheman (9th century) and Ibn-Fadlan(10th century). Al-Balkhi (10th century) described Bashkirs as a people divided into two groups, one inhabiting the Southern Urals, the second group living on the Danube plain near the boundaries of Byzantium——therefore – given the geography and date – referring to either Danube Bulgars or Magyars. Ibn Rustah, a contemporary of Al Balkhi, observed that Bashkirs were an independent people occupying territories on both sides of the Ural mountain ridge between Volga, Kama, and Tobol Rivers and upstream of the Yaik river.

Achmed ibn-Fadlan visited Volga Bulgaria as a staff member in the embassy of the Caliph of Baghdad in 922. He described them as a belligerent Turk nation. Ibn-Fadlan described the Bashkirs as nature worshipers, identifying their deities as various forces of nature, birds and animals. He also described the religion of acculturated Bashkirs as a variant of Tengrism, including 12 'gods' and naming Tengri – lord of the endless blue sky.

The first European sources to mention the Bashkirs are the works of Joannes de Plano Carpini and William of Rubruquis in the mid-13th century. These travelers, encountering Bashkir tribes in the upper parts of the Ural River, called them Pascatir or Bastarci, and asserted that they spoke the same language as the Hungarians.

During the 10th century, Islam spread among the Bashkirs. By the 14th century, Islam had become the dominant religious force in Bashkir society.

By 1236, Bashkortostan was incorporated into the empire of Genghis Khan.

During the 13th and 14th centuries, all of Bashkortostan was part of the Golden Horde. The brother of Batu-Khan, Sheibani, received the Bashkir lands to the east of the Ural Mountains – at that time inhabited by the ancestors of contemporary Kurgan Bashkirs.[citation needed]

During the period of Mongolian-Tatar dominion, some of the Bashkirs became subjects of the Kipchaks.[citation needed] Under the Golden Horde, they were subjected to different elements of the Mongols.[citation needed] After the breakup of the Mongol Empire, the Bashkirs were split between the Kazan Khanate, the Nogay Horde, and Siberian Khanate.[citation needed]

Early modern period[edit]

Bashkir women dressed in dulbega breast cover and kashmau headdress. 1770–1771.

In the late 16th and early 19th centuries Bashkirs occupied the territory from the left bank of the Volga on the south-west to the riverheads of Tobol in the east, from the river Sylva in the north, to the middle stream of the Yaik in the south, in the Middle and Southern Urals, in Cis-Urals, including Volga territory and Trans-Urals.

In the middle of the 16th century, Bashkirs joined the Russian state. Previously they formed parts of the Nogai,Kazan, Sibir, and partly, Astrakhan khanates. Charters of Ivan the Terrible to Bashkir tribes became the basis of their contractual relationship with the tsar’s government. Primary documents pertaining to the Bashkirs during this period have been lost, some are mentioned in the (shezhere) family trees of the Bashkir.

The Bashkirs rebelled in 1662–64 and 1675–83 and 1705–11. In 1676, the Bashkirs rebelled under a leader named Seyid Sadir or 'Seit Sadurov', and the Russian army had great difficulties in ending the rebellion. The Bashkirs rose again in 1707, under Aldar and Kûsyom, on account of ill-treatment by the Russian officials.

1735 Bashkir War[edit]

The main settlement area of the Bashkirs in the late 18th century extends over the Kama, Volga, Samara and Tobol Rivers

Bashkir officers, 1838–1845

The third insurrection occurred in 1735, at the time of the foundation of Orenburg, and it lasted for six years. From at least the time of Peter the Great there had been talk of pushing southeast toward Persia and India. Ivan Kirillov drew up a plan to build a fort to be called Orenburg at Orsk at the confluence of the Or River and the Ural Riversoutheast of the Urals where the Bashkir, Kalmyk and Kazakh lands join. Work was started at Orsk in 1735, but by 1743 'Orenburg' was moved about 250 km west to its present location. The next planned step was to build a fort on the Aral Sea. This would involve crossing the Bashkir country and then the lands of the Kazakh Lesser Horde, some of whom had recently offered a nominal submission.

Kirillov's plan was approved on May 1, 1734 and he was placed in command. He was warned that this would provoke a Bashkir rebellion, but the warnings were ignored. He left Ufa with 2,500 men in 1735 and fighting started on the first of July. The war consisted of many small raids and complex troop movements, so it cannot be easily summarized. For example: In the spring of 1736 Kirillov burned 200 villages, killed 700 in battle and executed 158. An expedition of 773 men left Orenburg in November and lost 500 from cold and hunger. During, at Seiantusa the Bashkir planned to massacre sleeping Russian. The ambush failed. One thousand villagers, including women and children, were put to the sword and another 500 driven into a storehouse and burned to death. Raiding parties then went out and burned about 50 villages and killed another 2,000. Eight thousand Bashkirs attacked a Russian camp and killed 158, losing 40 killed and three prisoners who were promptly hanged. Rebellious Bashkirs raided loyal Bashkirs. Leaders who submitted were sometimes fined one horse per household and sometimes hanged.

Bashkirs fought on both sides (40% of 'Russian' troops in 1740). Numerous leaders rose and fell. The oddest was Karasakal or Blackbeard who pretended to have 82,000 men on the Aral Sea and had his followers proclaim him 'Khan of Bashkiria'. His nose had been partly cut off and he had only one ear. Such mutilations are standard Imperial punishments. The Kazakhs of the Little Horde intervened on the Russian side, then switched to the Bashkirs and then withdrew. Kirillov died of disease during the war and there were several changes of commander. All this was at the time of Empress Anna of Russia and the Russo-Turkish War (1735–1739).

Although the history of the 1735 Bashkir War cannot be easily summarized, its results can be.

The Russian Imperial goal of expansion into Central Asia was delayed to deal with the Bashkir problem.

Bashkiria was pacified in 1735–1740.

Orenburg was established.

The southern side of Bashkiria was fenced off by the Orenburg Line of forts. It ran from Samara on the Volga east up the Samara River to its headwaters, crossed to the middle Ural River and followed it east and then north on the east side of the Urals and went east down the Uy River to Ust-Uisk on the Tobol River where it connected to the ill-defined 'Siberian Line' along the forest-steppe boundary.

In 1740 a report was made of Bashkir losses which gave: Killed: 16,893, Sent to Baltic regiments and fleet: 3,236, Women and children distributed (presumably as serfs): 8,382, Grand Total: 28,511. Fines: Horses: 12,283, Cattle and Sheep: 6,076, Money: 9,828 rubles. Villages destroyed: 696. As this was compiled from army reports it excludes losses from irregular raiding, hunger, disease and cold. All this was from an estimated Bashkir population of 100,000.

Later, in 1774, the Bashkirs, under the leadership of Salavat Yulayev, supported Pugachev's Rebellion. In 1786, the Bashkirs achieved tax-free status; and in 1798 Russia formed an irregular Bashkir army from among them. Residual land ownership disputes continued.

The Bashkirs lived between the Kama, Volga, Samara and Tobol Rivers. The Samara River extends from the hairpin curve of the Volga east to the base of the Urals. The Tobol is east of the Upper Ural River. Orsk is where the Ural turns westward. The Belaya River with the town of Ufa cuts through the center.

Demographics[edit]

The area settled by the Bashkirs in the Volga-Urals region according to the national census of 2010.

Further information: Bashkir language and Bashkortostan

The ethnic Bashkir population is estimated at roughly 2 million people (2009 SIL Ethnologue), of which about 1.4 million speak the Bashkir language, a Turkic language of the Kypchak group. The Russian census of 2002 recorded 1.38 million Bashkir speakers in the Russian Federation. Most Bashkirs are bilingual in Bashkir and Russian.

The 2010 Russian census recorded 1,172,287 ethnic Bashkirs in Bashkortostan (29.5% of total population).

About 50% of Bashkirs are Muslim, 25% are unaffiliated, 11% are atheist, and 2% are pagan. There are also about less than 1% Protestant and Catholic Bashkirs.[8][9]

Culture[edit]

The Bashkirs traditionally practiced agriculture, cattle-rearing and bee-keeping. The half-nomadic Bashkirs wandered either the mountains or the steppes, herding cattle.

Bashkir national dishes include a kind of gruel called öyrä and a cheese named qorot. Wild-hive beekeeping can be named as a separate component of the most ancient culture which is practiced in the same Burzyansky District near to the Shulgan-Tash cave.

«Ural-batyr» and «Akbuzat» are Bashkir national epics. Their plot concerns struggle of heroes against demonic forces. The peculiarity of them is that events and ceremonies described there can be addressed to a specific geographical and historical object –the Shulgan-Tash cave and its vicinities.

Religion[edit]

Caravanserai mosque in Orenburg, cultural monument of the Bashkir people, 1837—1844

In the pre-Islamic period the Bashkirs were followers of Tengrianism.[10][11]

Bashkirs began to convert to Islam from in the 9th century.[12] Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan in 921 met some of the Bashkirs, who were Muslims.[13] The final assertion of Islam among the Bashkirs occurred in the 1320s and 1330s (Golden Horde times). On the territory of Bashkortostan preserved the burial place of the first Imam of Historical Bashkortostan — The mausoleum of Hussein-Bek (ru), 14th-century building. In 1788 Catherine the Greatestablished the "Orenburg Mohammedan Spiritual Assembly (ru)" in Ufa, which was the first Muslim administrative center in Russia.

In yearly 1990s began the religious revival among the Bashkirs.[14] According to Talgat Tadzhuddin there are more than 1,000 mosques in Bashkortostan in 2010.[15]

The Bashkirs are predominantly Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi madhhab.[5]

Genetics[edit]

Regarding Y-DNA haplogroups, genetic studies have revealed that most Bashkir males belong to haplogroup R1b (R-M269 and R-M73) which is, on average, found at the frequency of 47,6 %. Following are the haplogroup R1a at the average frequency of 26.5%, and haplogroup N1c at 17%. In lower frequencies were also found haplogroups J2, C, O, E1b, G2a, L, N1b, I, T.[16]

Most mtDNA haplogroups found in Bashkirs (65%) consist of the haplogroups G, D, С, Z and F; which are lineages characteristic of East Eurasian populations. On the other hand, mtDNA haplogroups characteristic of European and Middle Eastern populations were also found in significant amounts (35%).[17][18]

Theories of origin[edit]

The Bashkirs, photo by Mikhail Bukar, 1872.

Because genetic studies have revealed that a majority of Bashkir males belong to Y-DNA Haplogroup R1b, which is otherwise concentrated in Western Europe, this has lent support to theories such as:

the "Kurgan hypothesis", i.e. that the original homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans lay immediately west of theUral Mountains, in or near present-day Bashkortostan,[19] and;

Notable Bashkirs[edit]

Alsou, singer (Bashkir father)

Lyasan Utiasheva, gymnast and TV personality (Bashkir mother)

Ildar Abdrazakov, opera singer

Murtaza Rakhimov, first president of Bashkortostan

Rustem Khamitov, president of Bashkortostan

Zeki Velidi Togan, historian, Turkologist, and leader of the Bashkir revolutionary and liberation movement

Salawat Yulayev, Bashkir national hero

Irek Zaripov, biathlete and cross-country skier

Tagir Kusimov, was a Soviet military leader.

Zaynulla Rasulev, was a Bashkir religious leader in the 19th and early 20th centuries

Kadir Timergazin, was also a Soviet petroleum geologist, the first doctor and professor of geological-mineralogical sciences from the Bashkirs, an honored scientist of the RSFSR.

Mustai Karim, was a Bashkir Soviet poet, writer and playwright. He was named People's poet of the Bashkir Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (1963), Hero of Socialist Labour (1979), and winner of the Lenin Prize (1984) and the State Prize of the USSR (1972).

Shaikhzada Babich, was a Bashkir poet, writer and playwright. Member of the Bashkir national liberation movement, one of the members of the Bashkir government (1917–1919).

Kharrasov Mukhamet – was a rector of the Bashkir State University (2000–2010), Ph.D in physics, Honorary worker of Higher professional Education of Russia (2002).

Yaroslava Shvedova - Kazakhstani tennis player (Bashkir mother)

References[edit]

Jump up^ Lewis, M. Paul (ed.) (2009). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition.". Dallas, Tex.: SIL International.

Jump up^ "ВПН-2010". Perepis-2010.ru. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

Jump up^ [1] Archived September 14, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

Jump up^ "8. НАСЕЛЕНИЕ НАИБОЛЕЕ МНОГОЧИСЛЕННЫХ" (PDF). Gks.ru. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

^ Jump up to:a b "Bashkortostan and Bashkirs", Encyclopedia.com

Jump up^ "Bashkirs", Great Russian Encyclopedia

Jump up^ Peter B. Golden, Haggai Ben-Shammai & András Róna-Tas, The World of the Khazars: New Perspectives, Leiden/Boston, Brill, 2007, pp. 422-423.

Jump up^ "Главная страница проекта "Арена" : Некоммерческая Исследовательская Служба "Среда"". Sreda.org. Retrieved 16 March2015.

Jump up^ "Numerical analysis" (JPG). Sreda.org. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

Jump up^ Shireen Hunter, Jeffrey L. Thomas, Alexander Melikishvili, "Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security", M.E. Sharpe Inc.

Jump up^ К вопросу о тенгрианстве башкир // Compatriot, Popular Science Magazine (Russian)

Jump up^ Shirin Akiner, "Islamic Peoples Of The Soviet Un", Second edition, 1986

Jump up^ Allen J. Frank, "Islamic Historiography and "Bulghar" Identity Among the Tatars and Bashkirs", Brill, 1998

Jump up^ Jeffrey E. Cole, "Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia", Greenwood publishing group

Jump up^ Интерфакс. Говорить о притеснении ислама в России кощунственно, считает Талгат Таджуддин // Interfax, 17.12.2010

Jump up^ Лобов А. С. Структура генофонда субпопуляций башкир. Диссертация кандидата биологических наук. — Уфа, 2009.- 131 с.

Jump up^ С. А. Лимборская, Э. К. Хуснутдинова, Е. В. Балановская. Этногеномика и геногеография народов Восточной Европы. Институт молекулярной генетики РАН. Уфимский научный центр. Медико-генетический научный центр РАМН. М. Наука. 2002. С.179-180

Jump up^ Антропология башкир/Бермишева М. А., Иванов В. А., Киньябаева Г. А. и др. СПб., Алетейя, 2011, 496 с., С.339.

Jump up^ See, for example: Will Chang, Chundra Cathcart, David Hall, & Andrew Garrett, 'Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis supports the Indo-European steppe hypothesis', Language, vol. 91, no. 1 (March) 2015, p. 196.

Sources[edit]

Frhn, "De Baskiris", in Mrn. de l'Acad. de St-Pitersbourg, 1822.

J. P. Carpini, "Liber Tartarorum", edited under the title "Relations des Mongols ou Tartares", by d'Avezac (Paris, 1838).

Semenoff, "Geographical-statistic Dictionary of Russian Empire", 1863.

Florinsky, in "Vestnik Evropy" magazine, 1874.

Katarinskij, "Dictionnaire Bashkir-Russe", 1900.

Gulielmus de Rubruquis, "The Journey of William of Rubruck to the Eastern Parts of the World", translated by V.W. Rockhill (London, 1900).

William of Rubruck's "Account of the Mongols", 1900.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bashkirs". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bashkirs". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.Alton S. Donnelly, "The Russian Conquest of Bashkiria 1552–1740": Yale Univ. Press, 1968.

Summerfield, Stephen Cossack Hurrah: Russian Irregular Cavalry Organisation and Uniforms during the Napoleonic Wars, Partizan Press, 2005 ISBN 1-85818-513-0

External links[edit]